Helmholtz Munich researchers revealed a conserved differentiation process with clinical implications for injury repair, identifying a multipotent fibroblast progenitor in the fascia— the deepest connective tissue layer of the skin. These CD201+ fascia progenitors control how quickly wounds heal by making different types of fibroblasts with different spatiotemporal patterns. These findings lay the foundation for modifying single fibroblast differentiation steps along the injury repair pathway to help identify new ways of treating different wound types.

The peer-reviewed research article “CD201+ fascia progenitors choreograph injury repair” was published today in Nature.

One fascia progenitor, two fibroblast gates

Wound healing is a conserved process that requires tight spatiotemporal tuning of consecutive phases. In the inflammatory phase, local signals trigger the innate immune system around the wound. For a wound to heal properly, it must move from the inflammatory phase to the proliferation phase. During this phase, myofibroblasts, a specialized fibroblast, make the wound’s extracellular matrix (ECM). When a wound heals, it goes through a final remodeling phase. During this phase, myofibroblasts make scar tissue that lasts for a long time.

Spatial and temporal tuning of tissue inflammation, contraction, and scar formation leads to the best tissue recovery and survival of the organism.

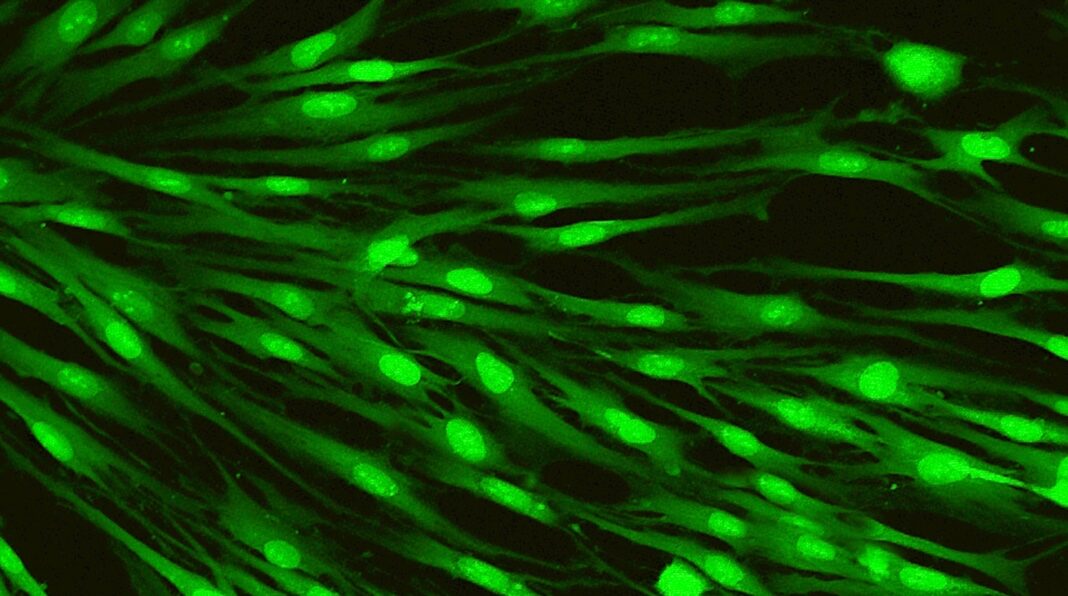

Donovan Correa-Gallegos, Haifeng Ye, Bikram Dasgupta, and their colleagues figured out the lineage progression of cells that help skin wounds heal. They found that CD201+-marked fascia progenitors are at the center of the injury repair process. They used skin injury models in mice, single-cell transcriptomics, genetic lineage tracing, ablation, and gene deletion models to show that changing how CD201+ progenitors differentiated changed how fibroblasts looked and slowed down the healing of wounds over time.

These CD201+ progenitors give rise to different types of fibroblasts, and two regulatory gates are needed for the wound healing phases to move along at the right time. The first change from fascia progenitors to proinflammatory fibroblasts greatly impacts the first phase of inflammation. When cells change from proinflammatory fibroblast to proto-myofibroblast, the second step is for them to become able to contract. This lets the healing process move from the inflammatory to the proliferation and remodeling phases.

The discovery of proinflammatory and myofibroblast progenitors and their differentiation pathways gives us a new way to look at and treat wounds that do not heal properly. Alterations in this differentiation process could impair wound healing and cause fibrotic scarring.

This new roadmap can inform treatment for specific wound types—such as surgical and keloid wounds and burns—and inflammatory skin diseases.