Researchers have discovered new connections between the gut and brain that hold promise for more targeted future treatments for depression and anxiety, and which could point scientists to ways of preventing digestive issues in children by limiting the transmission of antidepressants during pregnancy.

The study showed that increasing serotonin (5-hydroxtryptamine; 5-HT) in the gut epithelium—the thin layer of cells lining the small and large intestines—improved symptoms of anxiety and depression in animal models. Their findings from animal studies, and human data, collectively suggest that targeting antidepressant medications to cells in the gut could not only be an effective treatment of mood disorders like depression and anxiety but may also cause fewer cognitive, gastrointestinal, and behavioral side effects for patients and their children than current treatments.

“Antidepressants like Prozac and Zoloft that raise serotonin levels are important first-line treatments and help many patients but can sometimes cause side effects that patients can’t tolerate,” said research co-lead Mark Ansorge, PhD, associate professor of clinical neurobiology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. “Our study suggests that restricting the drugs to interact only with intestinal cells could avoid these issues.”

Added research co-lead Kara Margolis, MD, director of the NYU Pain Research Center and associate professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU College of Dentistry, “Our findings suggest that there may be an advantage to targeting antidepressants selectively to the gut epithelium, as systemic treatment may not be necessary for eliciting the drugs’ benefits but may be contributing to digestive issues in children exposed during pregnancy.”

Margolis, Ansorge, and colleagues reported their findings in Gastroenterology, in a paper titled, “Intestinal Epithelial Serotonin as a Novel Target for Treating Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction and Mood.”

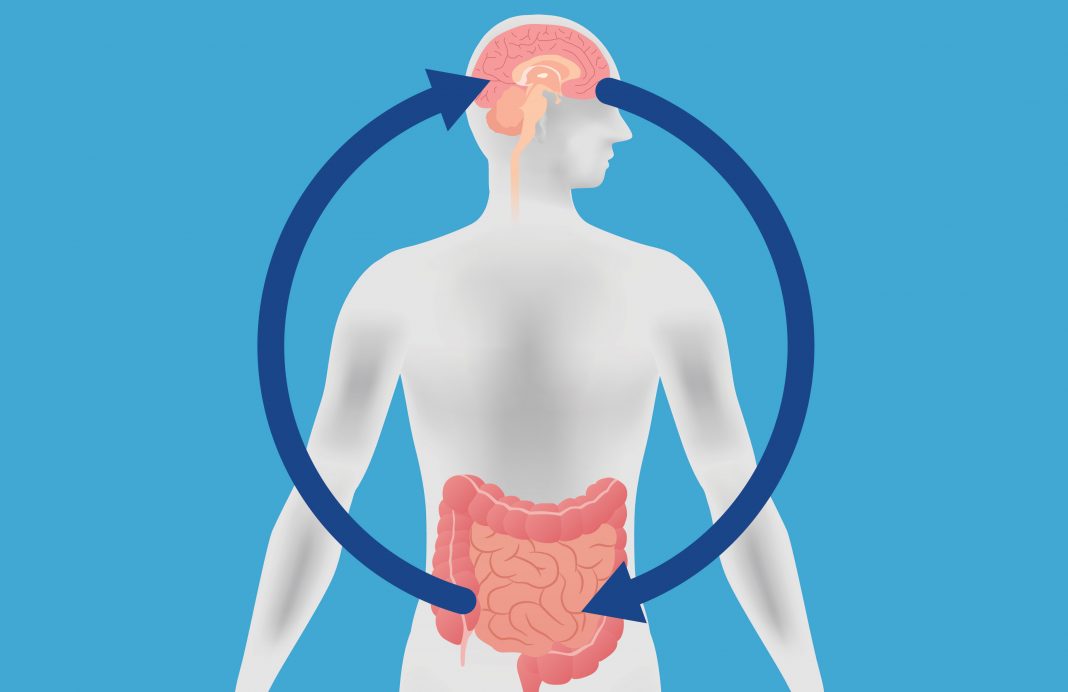

Anxiety and depression are among the most common mental health disorders in the United States, the researchers noted, citing figures indicating that one in five individuals experience symptoms. Many people with mood disorders also experience disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI), digestive issues such as irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation that result from communication issues between the gut and brain.

“Together, mood disorders and DGBI affect up to 40% of individuals globally,” the researchers continued. “Gut-brain communication has been increasingly recognized as a modulator of mood and DGBI symptoms. Insufficient knowledge about the signaling pathways involved, however, has impeded mechanistic insight and obstructed the development of targeted, highly effective therapies.”

Antidepressants—including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—are widely prescribed for depression, anxiety, and for treating the gastrointestinal symptoms that co-occur with these mood disorders. While these drugs are generally considered to be safe, they can come with side effects such as gastrointestinal issues and anxiety—“the very symptoms they are sometimes designed to treat,” said Ansorge—especially early during treatment with an SSRI, which may lead people to stop taking the medication. As the team stated, “Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are first-line pharmacological treatments for anxiety, depression, and co-morbid DGBI, less than 50% of those treated achieve remission … SSRIs can also induce adverse effects such as dysmotility, anxiety, and anhedonia, symptoms they are intended to treat.”

Antidepressants also pose challenges during and after pregnancy because of their ability to pass through the placenta and breast milk. Some studies show a higher incidence of mood and cognitive disorders in children exposed to SSRIs during pregnancy, although other studies have conflicting results. The authors noted, “SSRI treatment, moreover, poses challenges in pregnancy because SSRIs cross the placental and blood-brain barriers and can lead to alterations in central and enteric (CNS and ENS, respectively) neurodevelopment, which potentially impacts future mood, cognitive, and GI disorders.”

But untreated depression and anxiety during pregnancy have known risks for both the mother and baby, so expectant mothers have to weigh the potential risks of taking medication with their mental health needs. “… not treating a pregnant person’s depression also comes with risks to their children,” Ansorge said.

SSRIs work by blocking the serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) and raising serotonin levels in the brain. However, the vast majority of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut, and the serotonin transporter also lines the intestines. “In fact, 90% of our bodies’ serotonin is in the gut,” said Margolis, who is also an associate professor of pediatrics and cell biology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. SSRIs therefore increase serotonin signaling not just in the brain but also in the gut, raising the possibility that increasing serotonin signaling in the gut may impact gut-brain communication and ultimately mood. “For psychiatric medications that act on receptors in the brain, many of those same receptors are in the gut, so you have to consider the effects on gut development and function,” Margolis added.

However, the authors pointed out, that because SSRIs are absorbed systemically, precisely where they act to exert their therapeutic or adverse effects is unknown. “It is thus conceivable that intestinal epithelial 5-HT signaling impacts gut-brain communication and ultimately mood,” the team pointed out. “Whether SSRIs act on intestinal epithelial SERT to induce beneficial or adverse effects on behavior through gestational or adult exposure has not been explored.”

To better understand the connection between serotonin in the gut and mood and gastrointestinal disorders, the researchers studied several mouse models in which the serotonin transporter was removed or blocked. Previous studies led by Margolis found that mice bred to lack the serotonin transporter throughout the body, as well as mice that were exposed to SSRIs during and after pregnancy, experienced changes in the development of the digestive system and dysfunction in motility in the gut.

For their newly reported study, the researchers used a combination of genetic engineering, surgery, and pharmaceutical approaches to explore the role of serotonin in the gut specifically. They studied mice lacking the serotonin transporter in the gut epithelium either during development (mimicking exposure to an SSRI during pregnancy) or in young adulthood (akin to taking an SSRI as an adult). They found that removing the serotonin transporter from the gut epithelium increased serotonin levels and led to improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms in both groups of mice.

It also spared the animals from the adverse effects on digestion and motility that were found in the previous research where the serotonin transporter was missing or blocked throughout the body. “This adds a critical perspective to the long-held idea that the therapeutic effects of SSRIs come from directly targeting the central nervous system and suggests a role for the gut,” said Ansorge. “Based on what we know about interactions between the brain and gut, we expected to see some effect. But to see enhanced serotonin signaling in the gut epithelium produce such robust antidepressant and anxiety-relieving effects without noticeable side effects was surprising even to us.”

In their report, the team further stated, “Our observations suggest that endogenous 5-HT in the intestinal epithelium is a sufficient regulator of anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors; further, blockade of SERT-mediated intestinal epithelial 5-HT reuptake is both anxiolytic and anti-depressive.”

The researchers also determined that vagus nerves—a key highway of communication between the digestive system and brain—are the path by which serotonin in the gut epithelium modulates mood. The vagus nerve has long been known for its critical role in brain/gut communication, but mostly for top-down communication from the brain to the gut. Here the researchers found the other direction to be critical, with vagus nerve signaling from the gut to the brain. Cutting off this communication in mice in one direction—from gut to brain—removed improvements in anxiety and depression. The data, they noted, “… suggest that afferent vagal signaling from the GI tract mediates at least some of the effects of mood that are modulated by intestinal epithelial SERT.”

To explore whether blocking the serotonin transporter in humans leads to similar digestive issues as seen in mice, the researchers also looked at the use of antidepressants during pregnancy. They studied more than 400 pairs of mothers—a quarter of whom were taking antidepressants (SSRIs or SNRIs)—and their babies, and followed them during pregnancy and throughout the children’s first year of life.

The use of antidepressants during pregnancy significantly increased the risk of a child experiencing functional constipation—a common DGBI that may be painful—during their first year of life. “After adjusting for covariates, SSRI/SNRI exposure was associated with an over 3-fold increased risk for functional constipation,” the investigators wrote.

“We found that, at the age of one, 63% of children exposed to antidepressants during pregnancy experienced constipation, compared with 31% of children whose mothers did not take medication,” said study co-author Larissa Takser, MD, professor of pediatrics at the Université de Sherbrooke in Québec. “This finding suggests a potential connection between serotonin levels in utero and gut development, and opens new doors to examine SSRI properties not previously studied.”

The investigators’ collective findings point to a promising avenue of future studies: the gut epithelium as a new and potentially safer target for treating mood disorders, particularly for pregnant women. “Together, these data define a novel potential mechanism for gut-brain communication and identify intestinal epithelial 5-HT as a new and potentially safer therapeutic target for mood regulation,” the authors stated.

Margolis concluded, “Systemically blocking the serotonin transporter appears to play a role in the development of digestive issues in both mice and humans. However, restricting an antidepressant to inhibit the serotonin transporter only in the gut epithelium could avoid these adverse effects and limit the drug’s transmission during pregnancy and breastfeeding.”

The researchers do caution that their findings should not change clinical practice and influence whether mothers continue to take SSRIs during pregnancy due to the risk of constipation in their children, given the known risks of untreated maternal depression and anxiety.

“These are not clinical guidelines—rather, they are a call that more research is needed on the connection between SSRIs, serotonin, and the gut,” said Margolis. “It’s recommended that mothers and providers together consider treatment options that have been shown to be successful, including medications and cognitive behavioral therapy.” Added Ansorge: “Our findings indicate that we may be able to treat a mother’s depression or anxiety effectively without exposing the child … and we are working on drug delivery technology that will hopefully help us achieve that.”

In their discussion, the authors noted, “Our findings here contrast those obtained either with global deletion of SERT or systemic pharmacological blockade of SERT from gestation to weaning with an SSRI.” While global loss of SERT is associated with increased anxiety- and depression-related behaviors and impairments in cognitive function, the team suggests that restricted targeting of a drug to inhibit SERT only in the intestinal epithelium would avoid adverse effects. “Such a drug could thus be a novel, safe, and effective agent for the treatment of mood disorders and DGBI not only in adults but also in pregnant women.”