Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is characterized by pathological protein- and lipid-rich drusen deposits under the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and atrophy of the RPE monolayer in advanced disease stages—processes that no known drugs can combat. The result is photoreceptor cell death and vision loss. Now, using a stem cell-derived model (iPSC-RPE) that recapitulates these processes, researchers have identified two drug candidates that may slow AMD.

This work is published in Nature Communications in the paper, “Epithelial phenotype restoring drugs suppress macular degeneration phenotypes in an iPSC model.”

“This stem cell-derived model of dry AMD is a game-changer. Scientists have struggled to unravel this incredibly complex disease, and this model could prove to be invaluable for understanding the causes of AMD and discovering new therapies,” said Michael F. Chiang MD, director of the National Eye Institute (NEI).

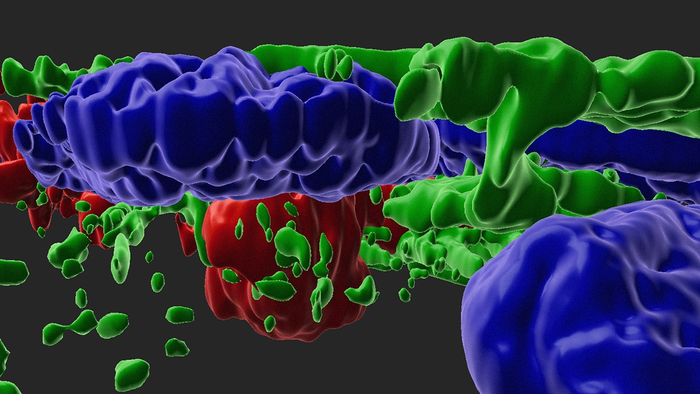

The investigators developed the model using stem cell-derived mature RPE cells. The cells were initially developed using skin fibroblasts or blood samples donated from AMD patients. Then, the fibroblasts or blood cells were programmed to become induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and then programmed again to become retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells.

The researchers used the model to screen drugs that slow or halt disease progression. Two drugs prevented the model from developing the key phenotypes of the accumulation of drusen and the atrophy, or shrinkage, of RPE cells.

Previous genetic studies had shown that some AMD patients have variants in genes responsible for regulating the alternate complement pathway, a key part of the immune system. However, it was unclear how the genetic variants led to disease.

One hypothesis was that patients with such variants lacked the ability to regulate the alternate complement pathway once it had become activated, resulting in the formation of anaphylatoxins, a type of protein that mediates inflammation, among other biological functions.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers exposed 10 iPSC-derived RPE cell lines involving different genetic variants to anaphylatoxins from human serum. They predicted that such a stress challenge would act as a surrogate for age-induced increases in alternate complement pathway that had been observed in the eyes of patients with AMD.

iPSC-derived RPE exposed to activated human serum developed key disease phenotypes: the formation of drusen, and RPE atrophy, which is associated with advanced disease stages. While signs of disease progression occurred among all 10 types of iPSC-derived RPE cells used in the study, they were worse in the iPSC-derived RPE from patients with high-risk variants in the alternate complement pathway, compared to those with low-risk variants, which gave the researchers a way to discern specific effects of genotype on disease characteristics.

Using the model, they screened more than 1,200 drugs from a library of pharmacological agents that had been tested for a range of other conditions. The screen flagged two drugs for their ability to inhibit RPE atrophy and drusen formation: the protease inhibitor aminocaproic acid, which likely directly blocks the complement pathway outside cells, and a second agent (L745), which stops complement induced inflammation inside the cell indirectly via inactivation of the dopamine pathway.

Of the two, L745 looks most promising and biologically interesting, according to Kapil Bharti, PhD, director of the NEI Ocular and Stem Cell Translational Research Section. The drug was developed by Merck & Co., and was originally tested for treating schizophrenia.

As an extension of the current work, the Bharti lab helped generate iPSCs from participants in a large NEI supported clinical study known as AREDS2. “We grew 65 iPSC-derived RPE lines and they are now being shared with the research community to create models for AMD research,” Bharti said. “This paper provides a framework to develop such models and thus has broad implications for the AMD research community.”