Researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU) have discovered that the immune cells known as B cells contribute to the “training” of the T cells in the thymus gland. If this process fails, autoimmune diseases can develop.

The findings are published in Nature in an article titled, “B cells orchestrate tolerance to the neuromyelitis optica autoantigen AQP4.”

“Neuromyelitis optica is a paradigmatic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system, in which the water-channel protein AQP4 is the target antigen,” the researchers wrote. “The immunopathology in neuromyelitis optica is largely driven by autoantibodies to AQP42. However, the T cell response that is required for the generation of these anti-AQP4 antibodies is not well understood. Here we show that B cells endogenously express AQP4 in response to activation with anti-CD40 and IL-21 and are able to present their endogenous AQP4 to T cells with an AQP4-specific T cell receptor (TCR).”

The team was led by Thomas Korn, PhD, professor of experimental neuroimmunology at TUM and a principal investigator in the SyNergy Cluster of Excellence, and Ludger Klein, PhD, professor of immunology at LMU’s Biomedical Center (BMC).

Neuromyelitis optica is an autoimmune disease similar to multiple sclerosis (MS). While it is not yet known which molecules are attacked in MS, it is well-established that T cells respond to the protein AQP4 in neuromyelitis optica. AQP4 is most prominently expressed in cells of the nervous tissue, which then becomes the target of the autoimmune reaction. Frequently, the optic nerve is affected.

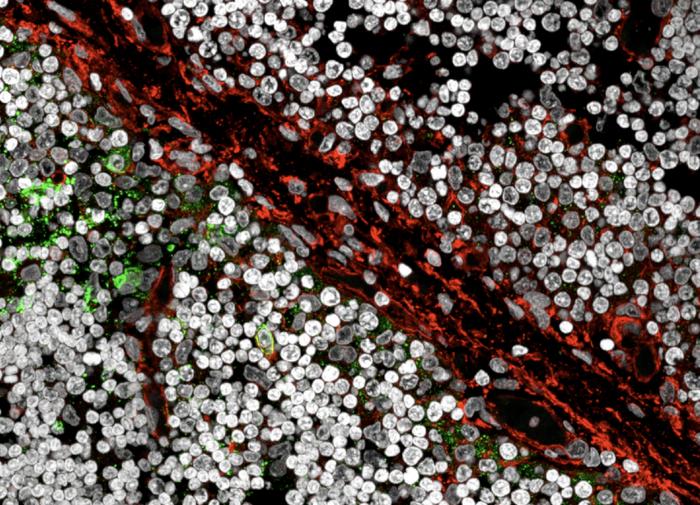

The researchers were able to show that in the thymus gland of humans and mice not only the epithelial cells but also B cells express and present AQP4 to the T cell precursors. If the B cells were prevented from doing so in animal experiments, AQP4-reactive T cell precursors were not eliminated and the autoimmune disease developed. This was also the case when the epithelial cells still presented the molecule. The team concludes from this that B cells in the thymus are a necessary condition for immune tolerance regarding AQP4.

“We suspect that this previously unknown process has evolved particularly to prevent dangerous interactions between autoreactive T and B cells in the lymph nodes and spleen, the so-called peripheral immune compartment,” explained Klein. Once the immune system is developed, B and T cells can communicate and thus trigger highly effective immune reactions. This is useful when it comes to fighting pathogens quickly. On occasion, however, B cells may accidentally present the body’s own proteins, such as AQP4. If the T cells that react to AQP4 had not been sorted out in the thymus, this could lead to a sudden and violent large-scale attack on the body.

“We assume that problems with the training of T cells by the B cells in the thymus can cause other autoimmune diseases as well,” said Korn. “After all, the B cells in the thymus present a whole range of the body’s own proteins. The corresponding interactions must be investigated in further studies.”

According to the researchers, likely suspects include antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and certain forms of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. “Looking further into the future, this interaction in the thymus might be exploited to treat existing autoimmune diseases in a very targeted manner,” said Korn.