First: transplant stem cells into hearts and other organs. Next: look for clinical outcomes. In other words: wait and see. That’s right. Stem cell transplantation—a cutting-edge form of regenerative medicine that is starting to show promise in clinical trials—isn’t subject to any sort of proper monitoring. At present, no tool exists that can assess the functionality of transplanted stem cells. Such a tool, however, may be emerging. Moreover, it may be capable of noninvasively and repeatedly delivering timely information. It is, in a word, the exosome.

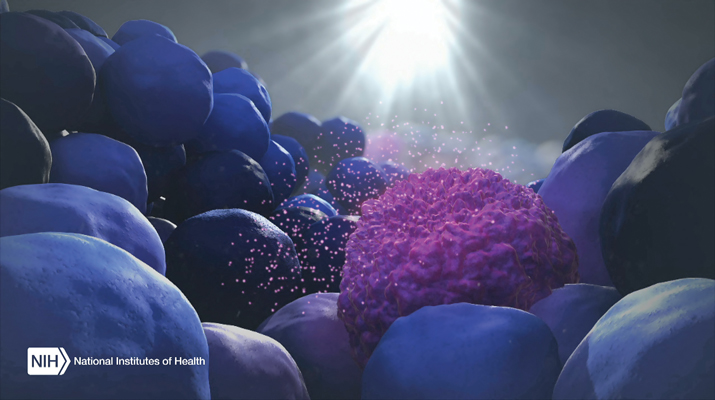

Exosomes are tiny membraneous vesicles that are secreted by cells into the blood. The exosomes that are released by transplanted stem cells, report scientists based at the University of Maryland (UM) and the University of Pennsylvania, can be analyzed for signs that the stem cells are working as desired. Even better, the exosomes can be collected noninvasively and repeatedly via simple blood draws.

Details of this work appeared May 22 in the journal Science Translational Medicine, in an article entitled, “Circulating exosomes derived from transplanted progenitor cells aid the functional recovery of ischemic myocardium.” The article describes how exosome monitoring was tested in rodent models of heart attack, or myocardial infarction.

The researchers transplanted two types of human cardiac stem cells—human cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) and cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs)—and monitored their circulating exosomes. Analysis of these exosomes showed that they delivered cell components to the target heart muscle cells, resulting in cardiac repair.

“To noninvasively monitor the activity of transplanted CDCs or CPCs in vivo, we purified progenitor cell–specific exosomes from recipient total plasma exosomes,” wrote the article’s authors. “Computational pathway analysis failed to link CPC or CDC cellular messenger RNA (mRNA) with observed myocardial recovery, although recovery was linked to the microRNA (miRNA) cargo of CPC exosomes purified from recipient plasma. We further identified mechanistic pathways governing specific outcomes related to myocardial recovery associated with transplanted CPCs.”

Blood plasma concentrations of the exosomes were compared seven days after transplant. Besides monitoring CDCs and CPCs and evaluating their role in aiding recovery, the researchers found that they produced in culture differed in contents from exosomes produced by transplanted cells in the living organism.

“Exosomes contain the signals of the cells they’re derived from—proteins as well as nucleic acids and miRNAs—which affect receptor cells and remodel or regenerate the organ we’re targeting,” said study co-senior author Sunjay Kaushal, PhD, MD, professor of surgery at UMSOM and director of pediatric cardiac surgery at the University of Maryland Children’s Hospital. “We now have a tool to determine whether stem cell therapy will be efficacious for an individual patient, not only for the heart but for any organ that received stem cell therapy.”

“Our study should be considered the first stepping stone in understanding what stem cells do, but an important point is that the cells we identified as responding changed their gene expression, behavior, and secretions,” added co-lead author Sudhish Sharma, PhD, UMSOM assistant professor of surgery. “By using these biomarkers, we can understand the mechanism and extent of recovery.”