A tightly regulated inflammatory response that is precisely turned on and then off is key for host protection against infection. However, in some instances, these pathways can be unnecessarily switched on and not off, leading to autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases. Now, researchers at Monash University report they have discovered a key mechanism in the body’s immune system that helps control the inflammatory response to infection.

The findings are published in The Embo Journal in an article titled, “Termination of STING responses is mediated via ESCRT-dependent degradation.” The new study could help pave the way for more targeted therapies in a range of inflammatory conditions.

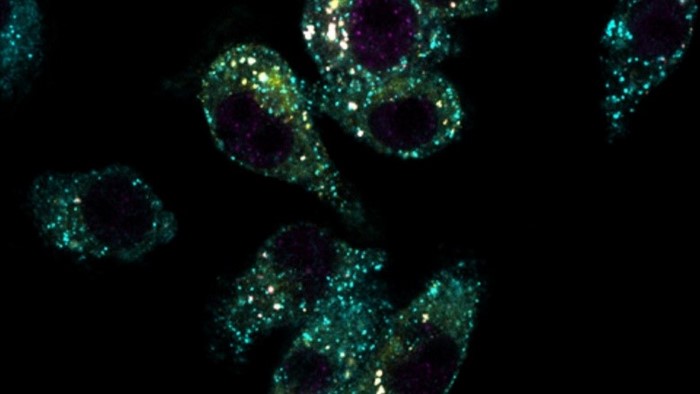

“cGAS-STING signaling is induced by detection of foreign or mislocalized host double-stranded (ds)DNA within the cytosol,” wrote the researchers. “STING acts as the major signaling hub, where it controls production of type I interferons and inflammatory cytokines. Basally, STING resides on the ER membrane. Following activation STING traffics to the Golgi to initiate downstream signaling and subsequently to endolysosomal compartments for degradation and termination of signaling. While STING is known to be degraded within lysosomes, the mechanisms controlling its delivery remain poorly defined. Here we utilized a proteomics-based approach to assess phosphorylation changes in primary murine macrophages following STING activation.”

“The innate immune system is ancient in our evolutionary history and is very robust,” Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute’s (BDI) senior researcher Dominic De Nardo, PhD, explained.

“The different components within the system are involved in detecting pathogens, mounting an inflammatory immune response, which should ultimately aid in the clearance of the threat, then signaling to the system that it’s time to shut off the inflammation.

“My group focuses on inflammatory responses induced by a central innate immune receptor —called Stimulator of Interferon Genes, or STING—that can alert the body to danger from pathogens, or be turned on by factors from within our own body that appear in the wrong place.

“The goal is to slow down and stop damaging inflammation in disease, driven by unwarranted turning on and/or inefficient shutting off of STING. We are looking forward to advancing this research further into human immune cells and preclinical studies.”

First author and recently graduated PhD student, Kate Balka, PhD, said the team wanted to understand how STING immune responses were regulated to ensure effective host immunity.

“We know on the one hand that STING responses are crucial for clearing pathogens, but on the other, unrestrained STING activity causes several inflammatory diseases including autoinflammatory, autoimmune, and neurodegenerative conditions,” Balka said.

“In other words, we wanted to understand and answer the question, how is STING turned off?”

The researchers determined the precise mechanisms controlling the termination of STING responses.

“In this study we have determined the molecular machinery, known as endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT), that packages STING into small compartments to allow it to be degraded, or broken down, by the lysosome—the cell’s ‘trash compactor’,” De Nardo said.