Surveillance Perspectives – Part I

NORTH AMERICA, AFRICA, EUROPE

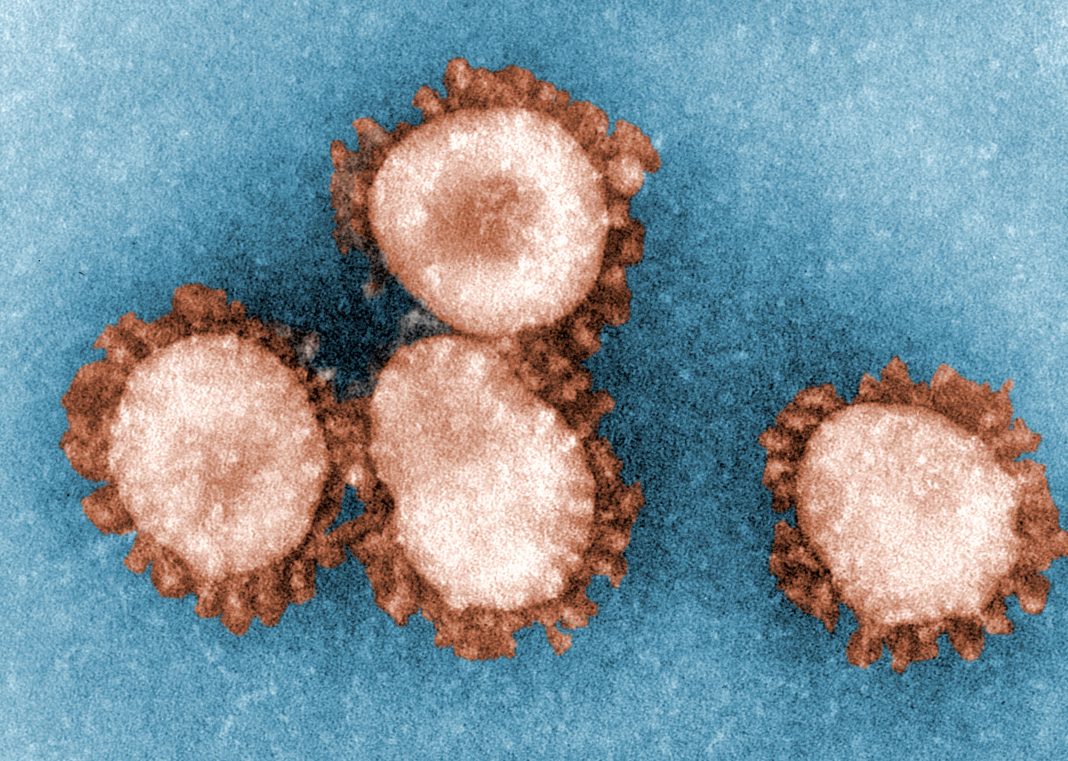

Since IMED 2018—the 7th International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance—the world has seen the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 and the accompanying unfolding of the COVID-19 pandemic. Advantaged by international travel, inequitable access to medical resources, and misinformation, COVID-19 has caused unprecedented morbidity and mortality not seen since the 1918 influenza pandemic.

IMED 2018 was succeeded by IMED 2021—the 8th International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance, a virtual event held last November. At IMED 2021, a fitting theme was chosen: “Many Voices, One Health.” It reflected the worldwide nature of COVID-19 and of the pandemic response. It was also appropriate in light of the mission fulfilled by the event’s organizer, the International Society for Infectious Disease (ISID).

ISID declares that it “supports health professionals, nongovernment organizations, and governments around the world in their work to prevent, investigate, and manage infectious disease outbreaks when they occur.” One of ISID’s initiatives is the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases (ProMED), an internet service that identifies unusual health events related to emerging and reemerging infectious diseases and toxins affecting humans, animals, and plants.

ISID’s goal for IMED 2021 was to host discussions about scientific and technological advances that could improve the detection, prevention, and response to outbreaks of emerging pathogens, as well as pandemic preparedness generally. The discussions were stimulated by speakers from around the globe. In this article, we revisit selected presentations that were delivered by speakers from North America, Africa, and Europe. For Asia-Pacific perspectives, please read the other article in this section of GEN.

Risks associated with climate change

One of the speakers at IMED 2021 was Kristie L. Ebi, PhD, professor of environmental and occupational health and of global health at the Center for Health and the Global Environment, Department of Global Health, University of Washington. Ebi has been conducting research on the health risks of climate variability and change for 25 years, focusing on understanding sources of vulnerability; estimating current and future health risks of climate change; designing adaptation policies and measures to reduce risks in multistressor environments; and estimating the health co-benefits of mitigation policies.

In her plenary talk, “Global Climate Change and Emerging Infectious Diseases,” Ebi said, “Projected climate change is expected to alter the geographic range and burden of a variety of climate-sensitive health outcomes and to affect the functioning of public health and healthcare systems. … If additional actions are not taken, then over the coming decades, substantial increases in morbidity and mortality are expected in association with a range of health outcomes, including heat-related illnesses, illnesses caused by poor air quality, undernutrition from reduced food quality and security, and selected vector-borne diseases in some locations.”

Ebi noted that climate change is a major driver of infectious disease events, matching or exceeding the influence of travel, tourism, and global trade. “We know that for illnesses such as dengue fever and yellow fever, early warning surveillance programs can save lives,” she pointed out. “The biggest challenge is the almost complete lack of funding to study climate change and disease from the World Health Organization as well as the National Institutes of Health.”

Of its $40 billion budget, the National Institutes of Health devotes only $9 million annually to research related to climate change and health. Ebi remarked that she sees some hope in the plans outlined by the Biden administration. The president has requested that the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention each receive over $100 million to address climate-related health issues.

Potential for next-generation sequencing

Another speaker at IMED 2021 was Christian Happi, PhD, a professor of molecular biology and genomics and one of the leaders of the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases in Nigeria. The topic of his plenary talk was “COVID-19, Ebola, Lassa Fever, and More—Application of Genomics in Epidemic Surveillance and Response.”

“Africa and Asia have a lot of experience with pandemics, ranging from Ebola, monkeypox, and SARS,” he said. “But we don’t have the ability to detect pandemics early due to limited resources.” He added that genomic surveillance is the best opportunity to prevent pandemics.

Happi used next-generation sequencing technology to determine the first sequence of SARS-CoV-2 in Africa, within 48 hours of receiving a sample from the first case in Nigeria. “Our finding,” Happi said, “provided insight into the detailed genetic map of the new coronavirus in Africa, confirmed the origin of the virus, and paved the way to the development of new countermeasures including new diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines.”

Happi observed that vaccination rates in Africa are extremely low: “Only 4% of Nigerians are vaccinated. Part of the problem is that COVAX has not supplied us with vaccines, and when they do, their expiration date is often just a month away.” He added that Africa made a mistake by not investing in vaccine manufacturing. He declared, “We must be more self-reliant in the future.”

There is also vaccine hesitancy in Africa. “Part of that is due to mistrust of the West, but part of that is because people are getting infected but not getting that sick or dying,” Happi related. “So, many people ask, why get vaccinated?”

Indeed, a tweet in January by the WHO African region noted that “while the peak and decline of this #COVID19 wave have been unmatched, #Africa is emerging with fewer deaths & lower hospitalizations. But the continent has yet to turn the tables on this pandemic.”

Early detection via monitoring of online and social media

Mathieu Roche, PhD, is a senior research scientist at CIRAD (Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement), the French agricultural research and cooperation organization working for the sustainable development of tropical and Mediterranean regions. Currently he is co-leader of MISCA (Modélisation de l’Information Spatiale extraction de Connaissance et Analyse), a research group at TETIS (Territoires, Environnement, Télédétection et Information Spatiale).

The title of his talk was “Mining Online and Social Media to Analyze Epidemic Periods.” Roche observed that event-based surveillance (EBS) systems monitor a broad range of information sources to detect early signals of disease emergence, including new and unknown diseases.

He summarized what he and his colleagues accomplished under the auspices of the MOOD project. (MOOD is short for MOnitoring Outbreaks for Disease surveillance in a data science context.) The project’s goal is to develop innovative tools and services for the early detection, assessment, and monitoring of current and future infectious disease threats across Europe in the context of continuous global, environmental, and climatic change.

“As we all know, in December 2019, a newly identified coronavirus emerged in Wuhan causing the COVID-19 pandemic,” Roche said. “My colleagues of the MOOD project and I conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the capacity of three EBS systems (ProMED, HealthMap, and PADI-web) to detect early COVID-19 emergence signals. We focused on changes in online news vocabulary over the period before/after the identification of COVID-19, while also assessing its contagiousness and pandemic potential.”

According to Roche, ProMED was the timeliest EBS, detecting signals one day before the official notification. “At this early stage, the specific vocabulary used was related to pneumonia symptoms and mystery illnesses,” he detailed. “Once COVID-19 was identified, the vocabulary changed to virus family and specific COVID-19 acronyms.”

Roche and his colleagues found that all three EBS systems were complementary regarding data sources, and that all require timeliness improvements. “EBS methods,” he concluded, “should be adapted to the different stages of disease emergence to enhance early detection of future unknown disease outbreaks.”

Infectious disease surveillance kits

Joseph Leonelli, PhD, senior vice president, ATCC Federal Solutions (AFS), ATCC, didn’t speak at IMED 2021, but GEN reached out to him for commentary because he manages a business unit that addresses emerging infectious diseases, biodefense, medical countermeasures, and global health security. AFS provides biological products, model systems, and custom solutions that support basic science, drug discovery, translational medicine, and public health.

“When the first reports came out about a mysterious illness in Hunan, China, we were asked by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) to take the early virus strains sent to them, expand them, and distribute them to research teams around the world,” he recalled. “Similarly, we were asked by NIAID to optimize testing kits for Zika for disease detection in South America.”

Leonelli and his colleagues helped to develop infectious disease surveillance kits for the Centers for Disease Control and provided expertise to Abbott, Becton, Dickinson and Company, and Thermo Fisher Scientific to develop diagnostic kits for COVID-19.

An optimistic outlook

The speakers at IMED 2021 lived up to the event’s “Many Voices, One Health” credo. Their “Many Voices” conveyed the message that the “One Health” community would weather the current pandemic through the development of vaccines, the dissemination of information at record speeds via open access publications, and the maintenance of data streams to help officials make informed decisions.

Read Next-Generation Sequencing Boosts Clinical Metagenomics, Surveillance Perspectives – Part II, ASIA–PACIFIC