Most concussions—mild traumatic brain injuries (TBIs)—aren’t treated. Only a fraction of people who experience concussions seek help, and those who do usually are only prescribed rest. For about 20 percent, however, rest doesn’t alleviate the symptoms. Those symptoms may persist for months or years, making daily life difficult. As yet, there is no FDA-approved treatment for mild TBI.

A few companies are addressing this increasingly-acknowledged problem by developing treatments that actually target the injury itself rather than just the resulting headaches, cognitive “fuzziness,” tiredness, or other symptoms. Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals, for example, just completed an exploratory Phase IIa trial for mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), and Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals recently completed Phase I trials for that indication.

Ignored until recently

“Until 20 years ago, most concussions weren’t treated or even recorded,” Christopher Nowinski, PhD, founding CEO, Concussion Legacy Foundation, tells GEN. “In mTBI, there is no damage to the brain that will show up on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and the symptoms often are dismissed by the patient and the doctor. Those symptoms, however, may persist for months or years and can be remarkably destructive.

Oxeia is developing a first-in-class synthetic human ghrelin—an endogenous hormone that crosses the blood-brain barrier—therapy to target the hippocampus. By restoring normal energy metabolism and reducing the toxicity caused by reactive oxygen species (which form in low-energy states), it treats the neuro-metabolic dysfunction and axonal injury that concussions cause.

A Phase IIa exploratory trial for OXE103 was launched in early 2020 at Kansas University Medical Center. The trial enrolled persistently symptomatic subjects within 28 days of their concussive injury. This patient population is expected to experience persistent symptoms for weeks to months or even years. The study enrolled 13 subjects who received OXE103 and six subjects who received standard of care—physical therapy and treatments for headaches and nausea. Standard of care treatments do not include therapeutic options to treat the underlying injury.

The results showed an 85 percent response rate in those treated with OXE103, versus a 33% response rate in those who received standard of care. “The data allow us to proceed to a larger clinical trial conducted at multiple sites across the U.S.,” says Michael Wyand, DVM, CEO, Oxeia.

Now Oxeia is raising funds to launch a 160-patient randomized Phase IIb trial. Favorable results could be a game-changer in how mild TBI is treated.

Distress signals

“The brain has a few mechanisms to heal itself, and a number of distress signals that indicate it’s in trouble,” notes William Korinek, PhD, co-founder and CEO of Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals. “One of those danger signals is adenosine.” When cells’ ATP energy levels are depleted, adenosine is released, which tells the astrocytes to go into action, utilizing alternative energy stores and clearing away more of the damaging excitatory neurotransmitters. “Our drug (AST-004) promotes that same set of intrinsic healing mechanisms.”

Korinek suggests AST-004 may aid recovery as well as halt further damage, based on preclinical results in both TBI and stroke.

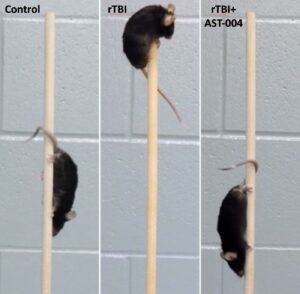

In earlier studies in young “teenager” mice that underwent a series of five concussions, treatment after each concussion contributed to significantly improved functionality months later when they were “middle-aged” compared to untreated, concussed mice. Another study showed that, in a vertical pole challenge, all the healthy control mice displayed normal motor function and scampered down the pole, but only about 40 percent of the repetitively concussed mice traversed the pole without stalling, compared to about 90 percent of the AST-004 treated mice.

Korinek says Astrocyte is developing an oral disintegrating tablet for mTBI that dissolves without water in a few seconds, making it easy for medics or sports coaches to administer it immediately after an injury. “It will take another year to advance this tablet into human studies,” he adds. An intravenous formulation for moderate-to-severe TBI and unconscious patients, however, is further along and is planned to enter Phase II trials in 2024.

Limited development activity

Many in the medical and scientific communities have the misperception that drug trials for mTBI have failed, Wyand says. “In reality, there have been few trials for concussion that have reached Phase II or Phase III trials.” An online database shows only 12 interventional Phase II or III studies for mild TBI. For context, the same search—but for Alzheimer’s disease—returned 921 trials.

As yet, most of the research in the U.S. is being conducted through academia, the NIH and the U.S. Department of Defense. The lack of widespread commercial development is narrowing the field of potential investors, adding to the challenges for companies developing this field.

Yet, concussion research appears to be on the brink of dynamic changes that will support fast, effective treatments. One year ago (March 2023), the FDA approved the first blood test (developed by Abbott) to assess the need for computed tomography (CT) scans in concussions as well as moderate-to-severe TBIs. It measures two biomarkers that, when they appear in large concentrations, are related to brain injuries.

When compared to positive CT scans, the test was nearly 96 percent accurate and can be used as a tool to determine who needs CT scans to assess TBI. The primary benefit, according to Abbott’s 510(k) filing with the FDA) is “a reduction in unnecessary computed tomography scans by approximately 40 percent.”

Other scientists (again, largely in academia) are exploring inflammatory biomarkers, salivary micro-RNAs and other potential biomarkers to further help triage patients for CT scans and provide insights into mTBI that the long-used Glasgow Coma Scale for moderate-to-severe TBI does not.

The other hurdle in the development of widespread clinical trials for concussion is the perceived lack of clearly defined study endpoints. Currently, neurologic diseases, including migraines, Parkinson’s disease, ALS, depression, and Alzheimer’s disease as well as concussions, are based on assessment of patient symptoms, Wyand points out.

“These endpoints are accepted as primary endpoints for approval of therapeutics by the FDA, and have specific guidance documents for validation,” he says. If biomarkers were required to conduct widespread clinical trials, “there would not be any drug development or approved drugs for any of these indications.”

“The science has evolved substantially in the past decade and we’re at the beginning of an exciting neuroscience wave,” according to Korinek. “We have so many more tools—such as biomarkers and imaging—to apply toward understanding injury differences and toward making the right clinical trial designs.

“This is an area that will be pretty exciting in the next five to 10 years, both in terms of finally having an acute treatment for concussions and, hopefully, something to prevent some of the long-term degeneration.” If those goals come to fruition, “that would be amazing.”