One barrier to progress in developing treatments for Crohn’s disease has been the lack of preclinical animal models that accurately replicate this complex autoimmune disorder. Another is the extreme heterogeneity among patients, making it difficult for clinicians to tailor therapies.

Previous studies of Crohn’s disease (CD) have derived organoids from pluripotent stem cells reprogrammed to become gut cells. University of California, San Diego (UCSD) researchers have now created a living biobank of organoids derived from adult stem cells in the gut tissue of Crohn’s disease patients—CD patient-derived organoid cultures (PDOs)—which more accurately replicated the traits of the disease. The results of their studies indicate that Crohn’s disease consists of two distinct molecular subtypes, a discovery that could, the team suggests, lay the foundation for improved diagnostics and the development of personalized treatments based on which subtype a patient’s disease falls into.

“It’s my hope that when the genetics are completed, Crohn’s disease will be viewed as two molecular subtypes that should be treated in two completely different ways,” said research lead Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor of cellular and molecular medicine and executive director of the HUMANOID™ Center.

Ghosh and colleagues reported on their work in Cell Reports Medicine, in a paper titled “A living organoid biobank of patients with Crohn’s disease reveals molecular subtypes for personalized therapeutics.” In their paper the investigators suggested, “CD PDOs may fill the gap between imperfect cell/animal models and limitations of CD GWASs and clinical trials and allow personalized therapy selection.”

Crohn’s disease is characterized by chronic inflammation of the digestive tract, resulting in a slew of debilitating gastrointestinal symptoms that vary from patient to patient. Complications of the disease can destroy the gut lining, requiring repeated surgeries. The poorly understood condition, which currently has no cure and few treatment options, often strikes young people, causing significant ill-health throughout their lifetime.

“Crohn’s disease (CD) is a complex and heterogeneous condition with no perfect preclinical model or cure,” the authors noted. “CD also lacks good preclinical animal models that faithfully recapitulate the diverse components of the human diseased tissue. Thus, CD continues to pose a challenge, and insights that can translate into personalization and precision in patient care are slow to emerge.”

Organoids are tiny, lab-grown replicas of organs or tissues that closely mimic the behavior of their real-life counterparts. They are especially useful in medical research when animal models do not adequately represent the disease.

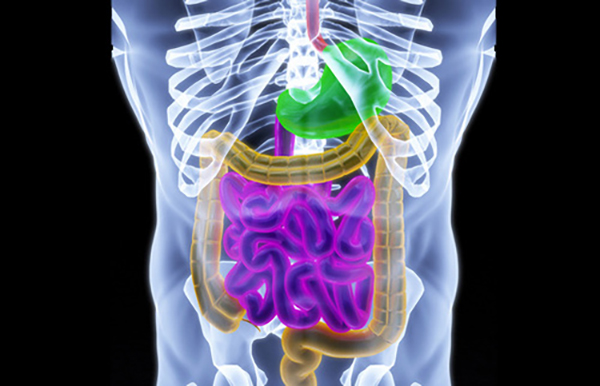

![Histology images of patient-derived organoids: healthy (left), Crohn’s disease SF2CD subtype (middle) and Crohn's disease IDICD (right). [Image courtesy of Pradipta Ghosh. UC San Diego Health Sciences]](https://www.genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Low-Res_3-PDOs-Composite-teaser-1200x628-1-300x157.jpg)

Adult stem cells retain an epigenetic memory of the gut environment imprinted on the genetic background—including a history of bacterial colonization, inflammation, and altered oxygen and pH.

For their study the researchers sampled gut tissue from 53 Crohn’s disease patients during routine colonoscopies at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at UC San Diego Health. The patients came from diverse backgrounds and presented with a variety of clinical symptoms. Scientists at the UC San Diego HUMANOID™ Center of Research Excellence at UC San Diego School of Medicine, led by its director and study first author Courtney Tindle, PhD, created a biobank of patient-derived organoid cultures.

Upon analysis, the researchers were surprised to discover that no matter how many clinically diverse patients they recruited, the organoids consistently fell into one of just two discrete molecular subtypes—each exhibiting unique patterns of genetic mutation, gene expression, and cellular phenotypes.

One subtype, termed immune-deficient infectious-Crohn’s disease (IDICD), was characterized by difficulty clearing pathogens, and an insufficient cytokine response by the immune system. “The IDICD subtype shows impaired pathogen clearance and insufficient cytokine response,” the team stated. These patients tend to form fistulas with pus discharge.

![Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor of cellular and molecular medicine and executive director of the HUMANOIDTM Center. [Erik Jepsen / University Communications]](https://www.genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Low-Res_240329PradiptaGhoshLabDSC_4084ErikJepsenUCSanDiego38-Crop-251x300.jpg)

Ghosh believes the discovery of these two distinct molecular subtypes will lead to a shift in the traditional understanding of Crohn’s disease. Instead of classifying patients based on a large array of clinical symptoms, categorizing them by one of the two molecular subtypes could open the door to more personalized and effective management strategies. “We show here that adult stem cell-derived organoids accurately mimic the inflamed gut, but the pluripotent cells fail, which reminds me of what Maya Angelou once said: ‘I have great respect for the past. If you don’t know where you’ve come from, you don’t know where you’re going.’”

Currently, because of a lack of understanding of these fundamentally different subtypes, they are all being given the same treatment, amounting to “a cookie-cutter therapy,” added Ghosh. “This combination of anti-inflammatory drugs helps a fraction of the patients, but only temporarily.”

The newly reported study revealed that patients with immune-deficient infectious-Crohn’s disease might instead be better served by therapies that clear their bacterial infections. In contrast, for those patients with the stress and senescence-induced fibrostenotic-Crohn’s disease subtype, Ghosh says drugs that target or reverse cellular aging—cell-based and stem cell-based therapies that rejuvenate the gut epithelium—might be more effective at treating their disease.

Testing different drugs on patient-derived organoids will help identify which drugs are most effective for each molecular subtype. “Our proof-of-concept studies also reveal that CD PDOs could be used to directly test drug efficacy in a personalized treatment approach,” the investigators commented. “PDOs could be classified into one of the two major molecular subtypes and subsequently tested for therapeutic efficacy using novel or clinically approved drugs within weeks after derivation.”

Ghosh added that work is underway to genotype the two subtypes in order to develop a simple test that can quickly identify which subtype a patient falls into. Ghosh suggests that future treatments for Crohn’s disease—which affects more than 500,000 people in the U.S.—could one day include personalized cell therapies, including gene editing and RNA-based treatments.

“Traditionally, we have been treating this disease with anti-inflammatory drugs, an approach that can be likened to putting out fires. With this study—the first of many based on the ongoing work and the efforts that are going to translate this to the clinic—we hope to target the arsonist who is responsible for the fire in the first place.”

In their paper, the authors concluded, “The major discovery we report here is the identification of two distinct molecular subtypes of CD—IDICD and S2FCD—based exclusively on the properties of the epithelial stem cells in the colon.” They added, “… our findings reveal the surprising potential for genotyped-phenotyped CD colon-derived PDOs as platforms for implementing personalized medicine. They also represent a paradigm shift in how we classify CD from clinical patterns to dysregulated molecular pathways that directly suggest therapeutic interventions.”