Researchers from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine said they have successfully applied genome sequencing to reveal what they said was the first complete picture of the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) disease within the U.K.’s East of England region.

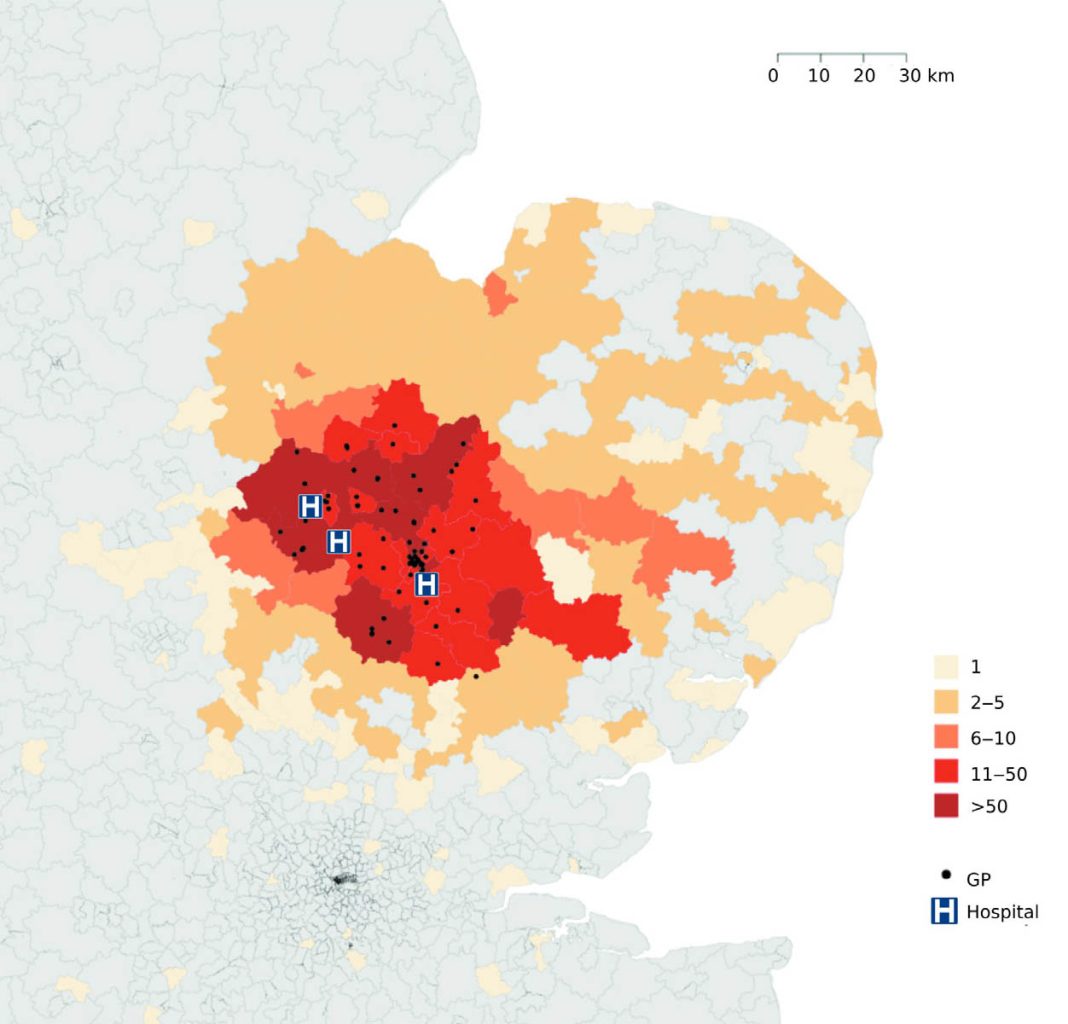

The researchers tracked MRSA-positive people to describe transmission of the infection within and between hospitals and in general practitioner (GP) surgeries and communities.

Combining sequencing of patients with information on when and where MRSA transmission may have occurred could link cases and detect outbreaks much sooner—helping prevent further transmission and reduce the number of people affected, the researchers concluded in “Longitudinal Genomic Surveillance of MRSA in the UK Reveals Transmission Patterns in Hospitals and the Community,” published yesterday in Science Translational Medicine.

“Our study provides a comprehensive picture of MRSA transmission in a sampled population of 1465 people and suggests the need to review existing infection control policy and practice,” the study added.

New MRSA carriers may be detected when patients are screened upon admission to the hospital, and doctors will look for links in time and place between patients to see whether an outbreak is underway. However, the researchers said, such traditional measures may miss MRSA transmission between people in hospitals and the community, as outbreaks in family or community groups can be difficult to detect. Worse, the measures are not sufficiently sensitive given the speed with which patients can move around the hospital or between hospitals.

Francesc Coll, Ph.D., of London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and colleagues, tracked every patient who had an MRSA-positive sample in the east of England over one year by sequencing the DNA of at least one MRSA strain from 1465 people (2282 samples in all), based on routine samples submitted to a diagnostic microbiology laboratory that served three hospitals and 75 GP surgeries.

The research team detected 173 different outbreaks or transmission clusters involving 598 patients, and discovered MRSA outbreaks in hospitals, in the community, GP surgeries, homes, and in between these places.

Of the transmission clusters, 118 (371 people) involved hospital contacts alone, while 27 clusters (72 people) involved community contacts alone, and 28 clusters (157 people) had both types of contact.

Most of the outbreaks had not been previously spotted. Community outbreaks were among people registered with the same medical practice or living in the same household or long-term care facility.

Community- and hospital-associated MRSA lineages were equally capable of transmission in the community, with instances of spread in households, long-term care facilities, and GP practices, the researchers reported.

Seeing “the Full Picture”

“Using whole-genome sequencing, we have been able to see the full picture of MRSA transmission within hospitals and the community for the first time,” Julian Parkhill, Ph.D., an author on the paper from Wellcome Trust Sanger, said in a statement. “We found that sequencing MRSA from all affected patients detected many more outbreaks than standard infection control approaches. This method could also exclude suspected outbreaks, allowing health authorities to rationalize resources.”

The researchers plan next year to begin a follow-up study, during which they plan to sequence MRSA strains from all new cases and share strain and track information in real time with infection control workers, with the goal of helping detect and exclude outbreaks, allowing targeted and effective treatment.

MRSA strains will be sequenced from all new cases and share strain and tracking information in real time with infection control workers. This will aim to help detect and exclude outbreaks, allowing targeted and effective interventions.

“Our study has shown that sequencing all MRSA samples as soon as they are isolated can rapidly pinpoint where MRSA transmission is occurring. If implemented in clinical practice, this would provide numerous opportunities to catch outbreaks early and target these to bring them to a close, for example by decolonizing carriers and implementing barrier nursing,” stated Sharon Peacock, Ph.D., study lead at Wellcome Trust Sanger and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. “We have the technology in place to do this, and it could have a really positive impact on public health and patient outcomes.”

The study was supported by grants from the UK’s Clinical Research Collaboration Translational Infection Research Initiative AQ7 and the Medical Research Council (grant no. G1000803) and others.