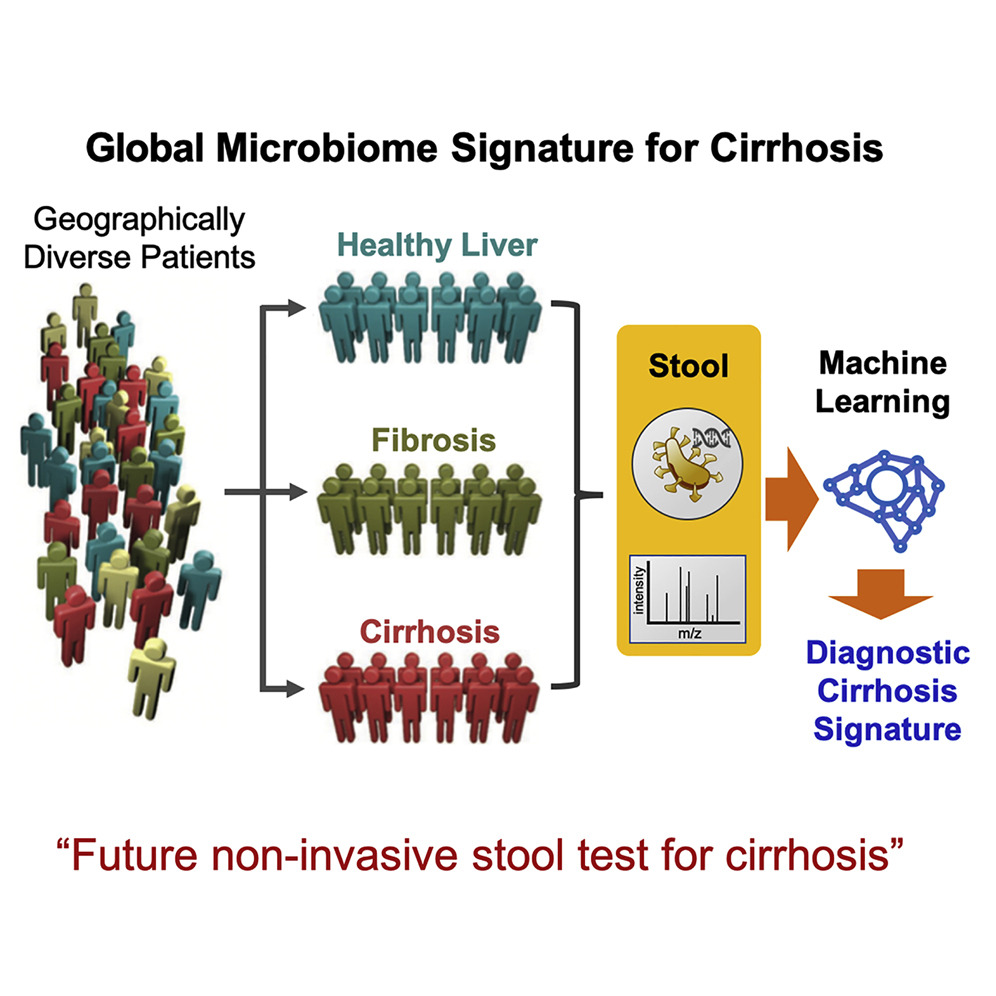

As evidence continues to emerge on the impact of the gut microbiome on a healthy lifestyle, scientists continue to search for diagnostic perturbations of microbial communities within the gut that could lead to disease detection. As such, a team of investigators, led by scientists at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine, have just published data showing that stool microbiomes—the collection of microorganisms found in fecal matter and the gastrointestinal tract—of Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients are distinct enough to potentially be used to accurately predict which persons with NAFLD are at highest risk for having cirrhosis.

NAFLD is the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, affecting an estimated one-quarter of the global population. It is a progressive condition that, in worst cases, can lead to cirrhosis—the late-stage, irreversible scarring of the liver that often requires eventual organ transplantation—liver cancer, liver failure, and death. Findings from the new study were published recently in Cell Metabolism through an article entitled “A Universal Gut-Microbiome-Derived Signature Predicts Cirrhosis.”

“The findings represent the possibility of creating an accurate, stool microbiome-based, non-invasive test to identify patients at greatest risk for cirrhosis,” explained senior study investigator Rohit Loomba, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and director of its NAFLD Research Center. “Such a diagnostic tool is urgently needed.”

Loomba noted that a novel aspect of the study is the external validation of gut microbiome signatures of cirrhosis in participant cohorts from China and Italy. “This is one of the first studies to show such a robust external validation of a gut microbiome-based signature across ethnicities and geographically distinct cohorts.

While previous work from Loomba and his colleagues has established a strong link between NAFLD and the gut microbiome, specific mechanisms have been scarce, and it has not been clear that discrete metagenomics and metabolomics signatures might be used to detect and predict cirrhosis. In the latest study, researchers compared the stool microbiomes of 163 participants encompassing patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis, their first-degree relatives, and control-patients without NAFLD.

Combining metagenomics signatures with participants’ ages and serum albumin (an abundant blood protein produced in the liver) levels, the scientists were able to accurately distinguish cirrhosis in participants differing by cause of disease and geography.

“To determine the diagnostic capacity of this association, we compared stool microbiomes across 163 well-characterized participants encompassing non-NAFLD controls, NAFLD-cirrhosis patients, and their first-degree relatives,” the authors wrote. “Interrogation of shotgun metagenomic and untargeted metabolomic profiles by using the random forest machine learning algorithm and differential abundance analysis identified discrete metagenomic and metabolomic signatures that were similarly effective in detecting cirrhosis (diagnostic accuracy 0.91, area under curve [AUC]). Combining the metagenomic signature with age and serum albumin levels accurately distinguished cirrhosis in etiologically and genetically distinct cohorts from geographically separated regions. Additional inclusion of serum aspartate aminotransferase levels, which are increased in cirrhosis patients, enabled discrimination of cirrhosis from earlier stages of fibrosis.”

The next step, said Loomba, is to establish causality of these gut microbial species or their metabolites in causing cirrhosis, and whether this test can be used and scaled up for clinical use.

“These findings demonstrate that a core set of gut microbiome species might offer universal utility as a non-invasive diagnostic test for cirrhosis,” the authors concluded.