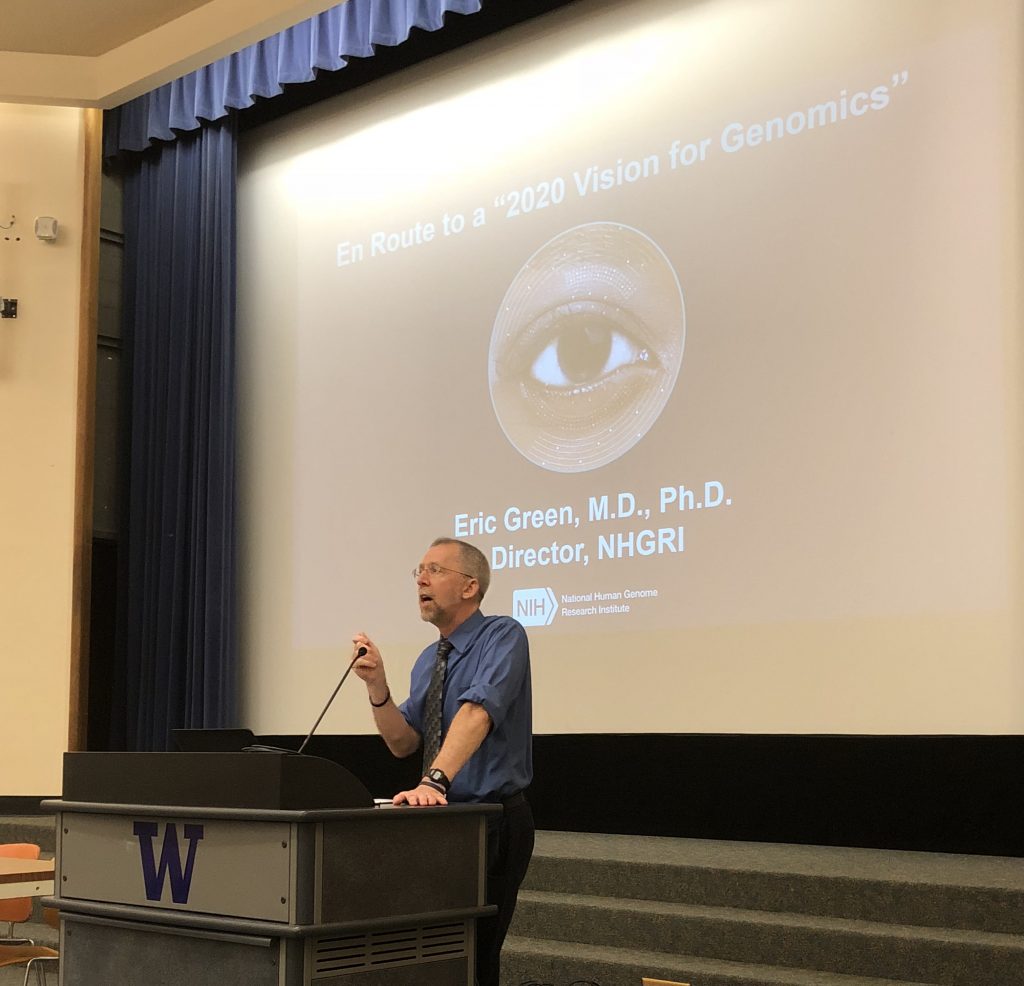

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) is nearing the halfway point of a major strategic planning process, one that aims to publish a “2020 vision for genomics” in late 2020. The new plan will “detail the most exciting opportunities for genomics research and its application to human health and disease at the dawn of the new decade.” In this exclusive interview, Eric D. Green, MD, PhD, the director of the NHGRI, discusses the process and some of the early takeaways from the planning effort.

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) is nearing the halfway point of a major strategic planning process, one that aims to publish a “2020 vision for genomics” in late 2020. The new plan will “detail the most exciting opportunities for genomics research and its application to human health and disease at the dawn of the new decade.” In this exclusive interview, Eric D. Green, MD, PhD, the director of the NHGRI, discusses the process and some of the early takeaways from the planning effort.

GEN: How is the development of this plan the same as or different from that of previous strategic plans?

Eric Green: It is helpful to consider the history of our institute. We were created 30 years ago by the U.S. Congress to lead the U.S.’s contribution to the Human Genome Project, but that project was completed 16 years ago. Therefore, our core mission had to change. Beginning 16 years ago, the institute has pivoted beyond the Human Genome Project and focused on enabling the use of genomics for understanding disease and improving the practice of medicine.

Eric Green: It is helpful to consider the history of our institute. We were created 30 years ago by the U.S. Congress to lead the U.S.’s contribution to the Human Genome Project, but that project was completed 16 years ago. Therefore, our core mission had to change. Beginning 16 years ago, the institute has pivoted beyond the Human Genome Project and focused on enabling the use of genomics for understanding disease and improving the practice of medicine.

One way to assess the NHGRI’s success involves looking at the uptake of genomics by other parts of the biomedical research ecosystem. I’ll give you some numbers because it frames a really important aspect of our strategic planning process.

When the Human Genome Project ended and we published our 2003 strategic plan, over 95% of human genomics research being supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was directly funded by the NHGRI.

When our next strategic plan came out in 2011, that number had fallen to just below 50%. So, while our 2011 strategic plan nicely summarized the important areas for the NHGRI to fund, there was already a large fraction of human genomic research being supported by other NIH institutes and centers.

What about now? Well, the NHGRI is funding only 15% of the human genomics research being supported by all of the NIH. This requires us to then really focus on the areas of genomics that are really at the forefront of the field—and thus the institute’s new mantra: The Forefront of Genomics.

In short, the biggest difference between this round of strategic planning and previous rounds is that now, genomics is disseminated in all the nooks and crannies of biomedical research. If we tried to do strategic planning for every area of genomics, it would just be too much. So, our efforts are now heavily focused on the cutting-edge “forefront” areas, especially those that will enable others in their use of genomics.

GEN: What is one of the most challenging aspects of the current round of strategic planning?

Eric Green: We have to engage many more groups. The field of genomics now extends far and wide—from establishing a basic understanding about how the human genome works to determining how genomic variation plays a role in human disease, and extending to how to use genomic information in the practice of medicine. Understanding the most compelling research questions in each of those areas requires engaging with many different groups, including patients. It gets more complicated because we’re touching medicine. The second you touch medicine, you touch patients, and therefore you’re touching society.

Another challenge relates to our emphasis on the Forefront of Genomics. For us to understand that forefront, we need to be talking to people whose work we want to enable over the next 10 years. So, we need to be talking to that hematologist searching for genomic variants to understand the basis of hematologic disease. And we want to know what are the tools and approaches that will enable that hematologist to do their science better.

While their work will likely be funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, we want to know what genomic tools and approaches they need to accomplish their goals. If we could design and develop the general toolkit for genomics, the work of many would benefit. Identifying those forefront challenges requires extensive engagement.

GEN: Has the town hall process been worth it? Have you received some unexpected or far-out ideas that have gained some traction? Who comes to the town halls?

Eric Green: There is no playbook for how best to do strategic planning. When we looked back at what we did in developing our 2003 and 2011 strategic plans, we realized that some approaches would likely still work but that we also needed to try new ideas—like the town halls. We’ve also held sessions at various scientific meetings, including some that focus on new areas for us like clinical meetings that we didn’t go to before. For example, we just got invited to do a strategic planning session at a major psychiatric genetics meeting in the fall. So far, we’ve done over 30 events, and we’re probably going to do another 10 or 15. That’s eight times more than we did for the 2003 strategic plan—but there’s just so much more ground to cover. Part of the reason we are holding more events is to capture input from specialized areas that are really relevant, especially around technology development, data science, or clinical applications of genomics. And we wanted that specialty input.

We put a high value on the actual engagement aspects of our efforts. If we hadn’t shown up in their backyard, we might have missed opportunities to learn about what is needed in the future. So, again we see value in that as part of our role of doing everything we can to catalyze genomics being done wide and far in biomedicine.

GEN: How are you ensuring that the strategic plan is going to be responsive to and resonant with the scientific community?

Eric Green: Your question is a very timely one because now that we’re at about the halfway point, we’re beginning to do what we affectionately refer to as pivoting. Initially, we mostly just showed up to events and listened. We didn’t want to steer the conversation because if we tried to steer it, we would inherently bias the conversation with our preconceived ideas. We deliberately emphasized listening in the first half.

Now, we’re starting to pivot and discuss what we’ve heard. Going forward, we’re giving people something to react to as opposed to having them give us open-ended input.

So, by pivoting, we’re starting to present half-baked synthetic ideas that might eventually be part of the strategic plan. Doing this gives us a chance to modify our ideas and correct course as needed. We get a chance to have our colleagues tell us what we got right or wrong and what is a higher or lower priority. Another way to say it is that the pivot is providing us checks and balances to make sure that our conclusions are resonating with the scientific community.

GEN: Are there some groups that you wish you were hearing from more?

Eric Green: Whenever we think of a group that we want to hear from, we find a way to talk with them. We wanted input from patient and community groups. So, we planned a meeting for this fall with those groups. As another example, we want input from other parts of the government, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). So, we are planning to get together with some FDA colleagues this summer.

GEN: How do you cope with the speed at which the genomic revolution is moving? As genomics expands, how do you try to ensure that the plan will still be relevant in even a year or two?

Eric Green: The plan cannot be so specific that it becomes outdated. Some things will happen quicker than anticipated, and some will happen slower than anticipated. We need to write it with a certain amount of audacity so that it’s unlikely it’s going to get outdated in a few years!

To be honest, I’m not terribly worried about that because I know that we will continue to face two massive challenges: understanding how the human genome actually works, and fundamentally changing the practice of medicine. Those two tasks are completely different, but they are both so incredibly complicated and cannot possibly happen quickly. We’re trying to lay out a blueprint for the next decade. And if it turns out that our strategic plan lasts only six years because things go much faster than anyone could have imagined, I will happily live with that bruise.

GEN: There remains some friction between believers in big science versus those who favor the payoffs of independent lab research. Will the plan include decisions on the relative investment in big multicenter science?

Eric Green: Probably not. This is a little tricky, and the NHGRI has always faced this issue with our strategic plans. Here, I make a distinction between a strategic plan and an implementation plan. Our strategic plan will describe what we think is the Forefront of Genomics. But it will not describe precisely how we are going to accomplish the major objectives. That is the role of the implementation plan.

While we may highlight the value of team science for accomplishing big goals in genomics, we also see the value of other approaches.

We want the strategic plan to be inspiring. Yes, it’s being written with the NHGRI’s general style for pursuing research in mind, but we won’t get into the nitty-gritty of how to organize that research. We want our strategic plan to be about the big ideas and goals.