Researchers from the Clemson University College of Science and the Heinrich Heine University in Germany say they have developed and demonstrated new optical imaging methods to monitor a single molecule in action. This fluorescence-based technique may accelerate the field of structural biology, helping scientists better understand how molecules are assembled, function, and interact, which in turn may aid in structure-guided drug design, according to the scientists.

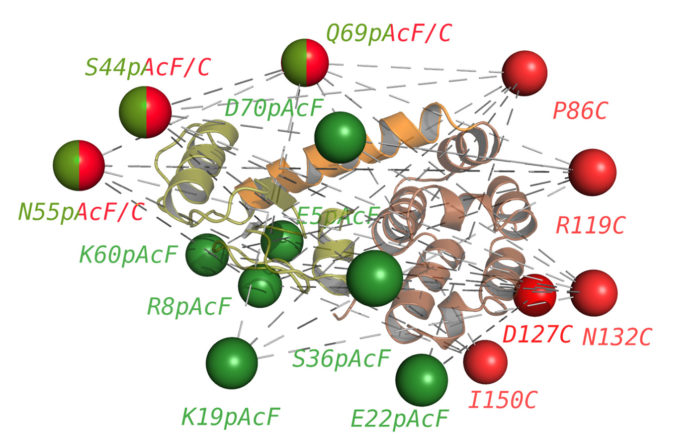

“We use a hybrid fluorescence spectroscopic toolkit to monitor T4 Lysozyme (T4L) in action by unraveling the kinetic and dynamic interplay of the conformational states. In particular, by combining single-molecule and ensemble multiparameter fluorescence detection, EPR spectroscopy, mutagenesis, and FRET-positioning and screening, and other biochemical and biophysical tools, we characterize three short-lived conformational states over the ns-ms timescale. The use of 33 FRET-derived distance sets, to screen available T4L structures, reveal that T4L in solution mainly adopts the known open and closed states in exchange at 4 µs,” write the investigators.

“A newly found minor state, undisclosed by, at present, more than 500 crystal structures of T4L and sampled at 230 µs, may be actively involved in the product release step in catalysis. The presented fluorescence spectroscopic toolkit will likely accelerate the development of dynamic structural biology by identifying transient conformational states that are highly abundant in biology and critical in enzymatic reactions.”

According to co-author Claus A.M. Seidel, PhD, chair of the Institute for Molecular Physical Chemistry at Heinrich Heine University in Germany, this work underpins essential reaction steps of biomolecular machines (enzymes). “Our FRET studies demonstrate the need of a third functional state in the famous Michaelis-Menten kinetics,” said Seidel. “The Michaelis-Menten description is one of the best-known models of enzyme kinetics.”

The centerpiece of this imaging tool is a FRET-based microscope, a sophisticated and powerful machine capable of visualizing biomolecules as small as a few nanometers. To visualize biomolecules at work, Sanabria and colleagues placed two fluorescent markers on a set of molecules, which created a ruler at the molecular level. By using different locations of the markers, the team collected a set of distances that describe the shape and form of the observed molecule. In essence, this process generated a collection of data points that were computationally processed, allowing the researchers to distinguish how the molecule looks and how it moves.

“We observe changes in the structure, and because our signal is time dependent, we can also get an idea of how the molecule is moving over time,” Sanabria said.

In his study, Sanabria and his team of collaborators combined the FRET-based microscope with molecular simulations to examine lysozyme, an enzyme found in tears and mucus. Lysozyme destroys the protective carbohydrate chains surrounding bacteria’s cell wall. Scientists widely use lysozyme to study protein structure and function because it’s such a stable enzyme.

“We can track the lysozyme of the bacteriophage T4 as it processes its substrate at near atomistic level with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution,” explained Sanabria. “We’ve taken the imaging field to a whole new level.”

Sanabria’s optical method revealed that the lysozyme structure is different than previously thought. Until now, scientists have largely determined the structures of proteins like lysozyme mainly using methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy.

“For the longest time, this molecule was considered a two-state molecule because of how it receives the substrate or cell wall of the target bacteria,” he said. “However, we have identified a new functional state.”

The team is helping to establish a database where their FRET-based structural models of similarly generated biomolecular models can be stored and accessed by other scientists. Together with the FRET community, the group is also working to establish recommendations for FRET microscopy.

Sanabria aims to apply his imaging methodology to other biomolecules. “This optical method can be used to study protein folding and misfolding or any structural organization of biomolecules,” Sanabria continued. “It can also be used for drug screening and development, which requires knowing what a biomolecule looks like in order for a drug to target it. This work is a milestone in structure determination using FRET to map short-lived functionally relevant enzyme states.”