Biosimilars, or copycats of biologic drugs, stray from clearly defined categories. Each biosimilar comes from a unique biomanufacturing environment and, consequently, possesses unique chemical attributes, which may or may not prove to be clinically relevant—most likely not (but worth checking).

Moreover, each biosimilar may go its own way, pursuing whatever developmental or marketing goals its license holder may have in mind.

Although they have many opportunities to deviate from predrawn regulatory, marketing, and prescription paths, biosimilars may be heading in the right direction. For example, “highly similar” biologics may start following procedures for establishing their interchangeability with their reference products, as well as with each other.

Herding biologic copycats over a shifting regulatory and pharmacy practice landscape won’t be easy, but a roundup has already commenced, as evidenced by the FDA’s guidances on naming biosimilars. What’s next? A biosimilars drive, one that promises to benefit many patients for whom the benefits of biologics might otherwise remain out of reach, even after the expiration of biologics’ patent protections. The drive is on track, even though the development, analysis, and market approval considerations for biosimilars are much more challenging than those for generic drugs.

What’s in a Name?

The biosimilars space is evolving, suggests Jesse Peterson, Pharm.D., clinical development manager, Fairview Pharmacy Services. Dr. Peterson devotes much of his attention to tracking emerging therapeutics, following the progress of biosimilars in the development pipeline, and analyzing approval trends. Dr. Peterson notes that as of April 2018, three of the nine biosimilars that have been approved by the FDA are commercially available.

“Through the end of 2018, there are at least eight biosimilar products with FDA review dates,” says Dr. Peterson. “In the coming months, we see additional opportunities to get exposure to these products.”

Although biosimilars continue to proliferate, they still need to penetrate the market. One barrier that could affect the penetration of biosimilars is the naming convention for these products. In addition to having a unique trade name, the FDA has added a unique four lowercase-letter hyphenated suffix to the core name of newly approved biosimilar products. These randomly generated suffixes differentiate FDA-approved biosimilars from the ones approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

While the FDA’s naming convention intends to minimize inadvertent substitutions and facilitate postmarketing analyses, an intentionally meaningless suffix could obscure a biosimilar’s association with a reference product. Also, suffix-carrying biosimilars could be perceived as being somehow inferior to suffix-free biologics, potentially decreasing patient and provider acceptance and slowing market penetration.

To help keep biologics and biosimilars on a level naming field, the FDA has started giving suffixes to biologics, too. “In November 2017,” Dr. Peterson observes, “the first originator biologic was assigned a four-letter suffix, and all newly approved biologics have followed that convention.”

Another barrier faced by biosimilars is pricing. In the current landscape of biosimilars, with relatively limited competition, originator products have been able to stay competitive with respect to pricing. “But as more biosimilar products become commercially available, we should see prices drop,” comments Dr. Peterson. And as biosimilars become less expensive, they may enjoy wider use, allowing providers gain more experience and confidence with these agents. Biosimilars may then become more recognized for their medical and pharmacy benefits.

Biosimilar Equivalence Testing

“Biological assays are very different from most physicochemical assays,” asserts David Lansky, Ph.D., president, Precision Bioassay. For example, biological assays are relatively poorly served by the traditional statistical methods that are used to establish similarity.

In a traditional test of similarity, the null hypothesis, which researchers are attempting to disprove, states that there are no differences between the responses recorded for a test product and the responses recorded for a reference product. “Statistics works beautifully in this setting,” remarks Dr. Lansky. However, for bioequivalence testing in the case of biosimilars, if the null hypothesis states that the test and reference responses are the same, and no evidence against the null hypothesis is obtained, one can incorrectly conclude that the test and reference responses are the same if an assay is noisy or if the amount of data that is analyzed is too small.

“Before trying to use the tests to show that two things are equivalent, we need to protect ourselves against making that claim by mistake, and that is very hard to do with traditional hypothesis testing,” cautions Dr. Lansky. Consequently, for biosimilar equivalence testing, the null hypothesis is usually turned around to state that a biosimilar is different, either superior or inferior, to the reference product.

“If we can disprove that, and we can control the way in which we falsely disprove it, we can be confident that the two variables are the same,” explains Dr. Lansky. “This is why we use the equivalence test.”

Although equivalence testing for similarity in bioassays has become broadly accepted, the shift from difference testing has been accompanied by the rise of a new challenge. One may find it necessary to set the margins or bounds of the equivalence tests.

“There is guidance on how to do this in the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) regulatory documents,” states Dr. Lansky. The USP describes four approaches to support the bounds for equivalence limits. However, three of these approaches involve using historical data to compare a standard or a reference to itself.

“All three ‘historical data’ approaches are quite dangerous because they essentially measure the capability of the assay,” insists Dr. Lansky. The fourth method recommends incorporating some type of sensitivity analysis to ask how much nonsimilarity actually matters. In a recent research effort, Dr. Lansky and colleagues proposed a complete method to set equivalence bounds that depends only on assay performance requirements, and not on assay capability.

In an assay that has been developed to support a product, the performance requirements must provide information about parameters, such as how much degradation or loss of potency may be tolerated or how much manufacturing variation is acceptable. “All those get wrapped up into a package to express product specifications, measure the capability of the method, and manage the product,” explains Dr. Lansky. From the package, which must work as a whole, it is possible to extract limits on bias, which provide limits on nonsimilarity.

“Those limits are not driven by the capability of the assay, but by the needs of the consumers and producers,” asserts Dr. Lansky. “This approach ensures that the product is effective, safe, and reproducible, and this is what universal equivalence bounds is about.”

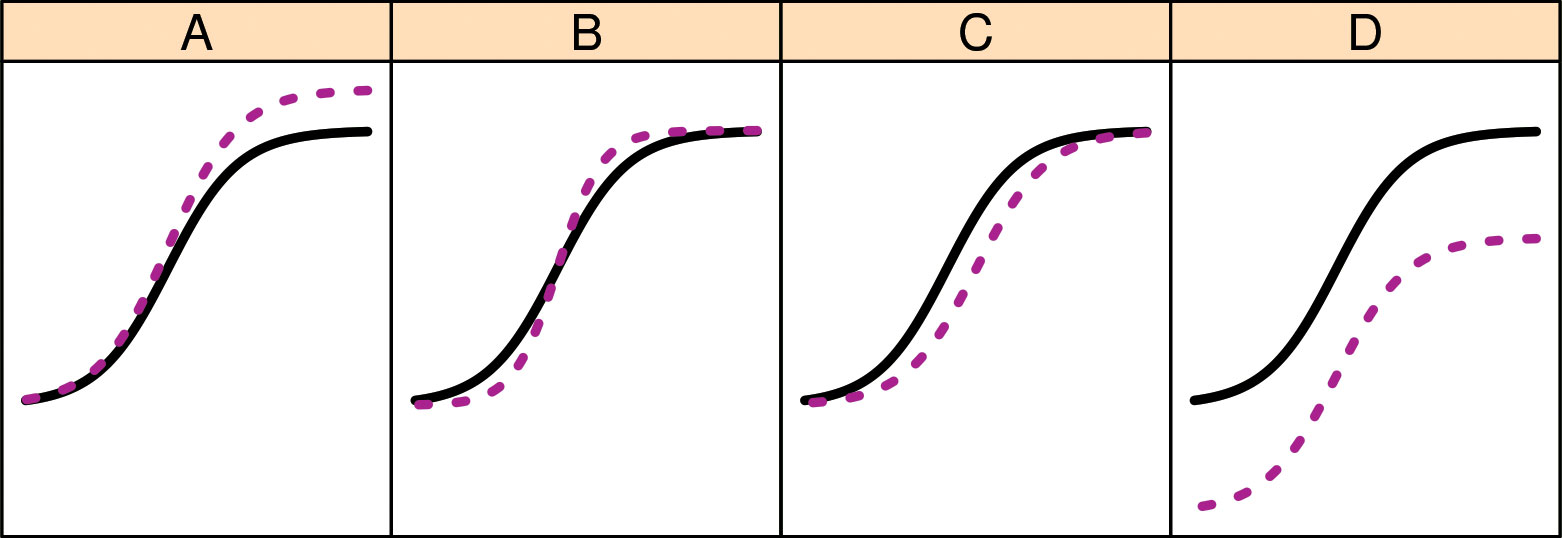

Statistical methods for similarity testing, says Precision Bioassay, may focus on several curve parameters and how they differ between test and reference dose-response curves: A: nonsimilarity of range (difference between asymptotes); B: nonsimilary of curve shape; C: log potentcy or activity shift; and D: nonsimilarity of the no-dose asymptote. Assessing biosimilarity usually includes assessing all four curve parameters. Positively correlated shifts in A and D will cause appreciable bias in estimates of log potency (differences in C).

Trends in Biosimilar Costs

“As we gain more experience in the U.S. marketplace, and develop multiple biosimilars for the same agent, we will probably see their price come down,” says Richard Brook, president, Better Health Worldwide. Mr. Brook performs retrospective claim analyses and strategic consulting for pharmaceuticals and biosimilars. Part of this work focuses on managed care access intervention programs, which aim to identify value propositions that would be favorable to payers.

Although it is anticipated that the introduction of biosimilars will lead to savings, the magnitude of these savings remains unclear. “We have yet to see some of these benefits and discounts go back to the members or in many cases to the health system,” complains Mr. Brook.

Savings shortfalls may be due to slow development, approval, and adoption of biosimilars; legal challenges by the reference product manufacturers; negotiations over rebate terms; and payment structures that base benefits on published price and exclude rebates. Such factors could increase costs for beneficiaries over those of the reference product. “They could,” adds Mr. Brook, “make it harder for companies to put their biosimilars into the market.”

Regulatory Considerations

The development and approval of biosimilars raises regulatory and practical considerations. The regulatory considerations are becoming defined, thanks to the guidelines issued by the EMA and the FDA. The practical considerations, however, can be relatively unclear. For pharmacists, practical considerations include naming and labeling issues; logistics and reimbursement practices; and usage standards with respect to interchangeability, substitution, and indication extrapolation.

Both regulatory and practical considerations preoccupy James Stevenson, Pharm.D., professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy. In his capacity as a pharmacy practitioner and healthcare administrator, Dr. Stevenson focuses on tracking the regulatory process and analyzing how biosimilars are integrated into health systems.

For example, Dr. Stevenson is familiar with indication expansion, or the process whereby a biosimilar is approved for an indication held by the originator biologic. This process may accommodate a biosimilar that has not been evaluated in clinical trials specifically for the relevant indication.

“We are becoming much more comfortable with the regulatory process and with extrapolation to indications not specifically studied in the biosimilar approval process,” comments Dr. Stevenson. Extrapolation is carried out most confidently, he suggests, if it concerns drugs for which the mechanism of action and site of action are well understood.

“A trend toward more assured extrapolation is reflected in recent statements by medical organizations,” asserts Dr. Stevenson. “These organizations have also begun to be more comfortable with the ability to conduct limited switching of patients from a reference product to a biosimilar.”

To date, over 35 biosimilars have been approved by the EMA, but only nine by the FDA. This discrepancy reflects how biosimilar approvals started relatively late in the United States. In Europe, biosimilar approvals commenced in 2006. In the United States, they began 10 years later.

“In the United States,” Dr. Stevenson points out, “we did not even have a legal process to create the regulatory framework until 2010.” The number of biosimilars on the U.S. market (only three at this time) has been limited by prolonged U.S. patent issues. “It is frustrating that we have approved products that have yet to be marketed properly,” complains Dr. Stevenson.

A key distinction between the biosimilar space in Europe and in the United States is that the FDA regulatory process contains the designation of an interchangeable biosimilar. “The EMA does not have that designation,” informs Dr. Stevenson, “and it is up to the individual countries what their policies are on interchangeability.”

The FDA designation of interchangeability, which was established early on, reflects a conservative approach and accounts for the possibility that that a reference product can be substituted with a biosimilar without the intervention of the healthcare provider who originally issued the prescription. “While this was well intended,” suggests Dr. Stevenson, “as we get more and more data indicating that one can safely switch patients from a reference product to a biosimilar, this might be a barrier that we ultimately might regret.”