![The signals required for regulatory B (Breg) cell differentiation in humans are currently unknown. This diagram depicts what Mauri and colleagues show, that plasmacytoid dendritic cells, via the provision of interferon-alpha, govern the differentiation of immature B cells that restrain inflammation. [Menon et al./Immunity 2016]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/110303_web2012361662-1.jpg)

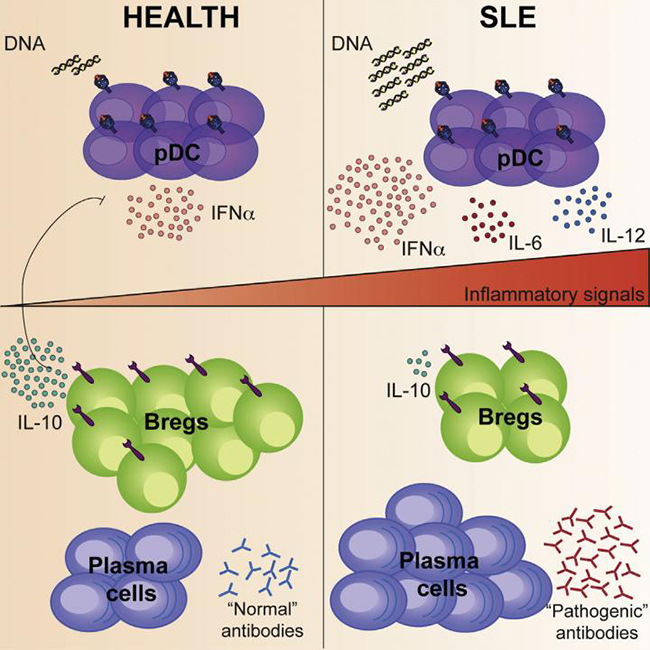

The signals required for regulatory B (Breg) cell differentiation in humans are currently unknown. This diagram depicts what Mauri and colleagues show, that plasmacytoid dendritic cells, via the provision of interferon-alpha, govern the differentiation of immature B cells that restrain inflammation. [Menon et al./Immunity 2016]

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is an enigmatic disease characterized by a hyperactive immune system that attacks normal cells, affecting various body systems such as joints, kidneys, blood cells, heart, lungs, and most noticeable to others, the skin—from which the disease is often first diagnosed due to the classic butterfly rash on the face. Researchers have been searching for decades—to no avail—for the reason immune cells, which would normally keep inflammation at bay, can't seem to do their job in SLE patients.

However now, a team of scientists from the University College London has recently published a study suggesting that B cells regulating inflammation are getting signaled to become pro-inflammatory cells instead in SLE patients. The investigators studied human blood samples and genetic profiles, which also provided evidence or a strong connection between how lupus patients respond to treatment and their levels of these cellular signals.

The findings from this new study postulate that the miscommunication in lupus patients seems to come from an imbalance of three types of immune cells: B cells that produce antibodies to protect the body against foreign microbes (and a primary driver of autoimmune disorders), plasmacytoid dendritic cells that produce a molecular signal called interferon-alpha (IFN-α) that stimulates B cells, and regulatory B cells that suppress excessive immune responses, which are severely lacking in lupus patients.

“Our study shows for the first time that the overproduction of IFN-α by hyperactivated plasmacytoid dendritic cells in lupus patients is the consequence of the lack of suppressive regulatory B cells,” explained senior study author Claudia Mauri, Ph.D., professor of immunology at University College London. “The uncontrolled production of IFN-α causes an increase of antibody-producing B cells and suppresses the division and appearance of regulatory B cells.”

The results of this study were published recently in the journal Immunity in an article entitled “A Regulatory Feedback between Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells and Regulatory B Cells Is Aberrant in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.”

Interestingly, the researchers also discovered a potential reason rituximab, a drug that has long been used off-label to treat lupus by depleting the vast majority of circulating B cells, benefits some patients with SLE, but not others. The scientists were able to gather a range of data after analyzing immune cells and genetic activity from nearly 100 healthy volunteers and 200 people with lupus.

“After treatment, newly formed B cells come back into circulation,” noted lead author Madhvi Menon, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Mauri's lab. “Our study suggests that response to rituximab is determined by the presence or absence of an elevated IFN-α–related gene activity. Thus, only in patients that have a normal IFN-α signature do the newly repopulated B cells successfully mature into regulatory B cells.”

The University College of London scientists were excited by their findings because the results seem to suggest that lupus patients should be tested for this IFN-α–related gene signature prior to treatment with rituximab. “This would be an important step towards personalized medicine for the treatment of lupus,” Dr. Mauri concluded.