Research has shown that sarcomas and carcinomas have proven more resistant to CAR T immunotherapy approaches in part because engineered T-cells progressively lose tumor-fighting capacity once they infiltrate a tumor. Immunologists call this cellular fatigue T-cell “exhaustion” or “dysfunction.”

In efforts to understand why, La Jolla Institute for Immunology investigators Anjana Rao, PhD, and Patrick Hogan, PhD, have published a series of papers over the last years reporting that a transcription factor that regulates gene expression, called NFAT, switches on downstream genes that weaken T-cell responses to tumors and thus perpetrates T-cell exhaustion. One set of these downstream genes encodes transcription factors known as NR4A, and a previous graduate student, Joyce Chen, showed that genetic elimination of NR4A proteins in tumor-infiltrating CAR T cells improved tumor rejection. However, the identity of additional players cooperating with NFAT and NR4A in that pathway has remained unknown.

In a study (“TOX and TOX2 cooperate with NR4A transcription factors to impose CD8+T cell exhaustion”) published online in PNAS from the Rao and Hogan labs, a more complete list of participants in a gene expression network that establishes and maintains T-cell exhaustion is described. The work employs a mouse model to show that genetically eliminating two new factors, TOX and TOX2, also improves eradication of solid melanoma tumors in the CAR T model. This research suggests that comparable interventions to target NR4A and TOX factors in patients may extend the use of CAR T-based immunotherapy to solid tumors.

The group began by comparing gene expression profiles in samples of normal versus exhausted T cells, searching for factors upregulated in parallel with NR4A as co-conspirators in T-cell dysfunction. “We found that two DNA binding proteins called TOX and TOX2 were consistently highly expressed along with NR4A transcription factors,” said Hyungseok Seo, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Rao lab and the study’s first author. “This discovery suggested that factors like NFAT or NR4A may control expression of TOX.”

The group then recapitulated a CAR T protocol in mice by first inoculating animals with melanoma tumor cells to establish a tumor, and then a week later infusing mice with one of two collections of T cells: a control sample from a normal mouse, versus a sample derived from a mouse genetically engineered to lack TOX and TOX2 expression in T cells.

Mice infused with TOX-deficient CAR T cells showed more robust regression of melanoma tumors than did mice infused with normal cells. Moreover, mice treated with TOX-deficient CAR T cells exhibited increased survival, suggesting that loss of TOX factors combats T-cell exhaustion and allows T cells to destroy tumor cells more effectively.

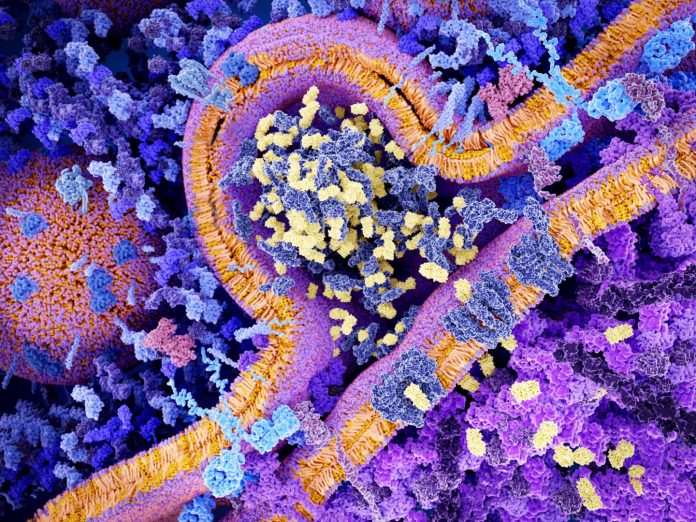

Additional analysis led the investigators down a pathway ending with a well-known immune adversary. The researchers showed that TOX factors join forces with both NFAT and NR4A to promote expression of an inhibitory receptor called PD-1, which decorates the surface of exhausted T cells and sends immunosuppressive signals.

PD-1 is blocked by numerous checkpoint inhibitors, which combat immunosuppression and activate an innate anticancer immune response. Convergence of TOX, NFAT, and NR4A on PD-1 makes molecular and immunological sense and puts it at the convergence of both cellular and antibody immunotherapy approaches, according to the team.

“Currently, CAR T cell therapy shows amazing effects in patients with ‘liquid tumors’ such as leukemia and lymphoma,” said Seo. “But they still do not work well in patients with solid tumors due to T-cell exhaustion. If we could inhibit TOX or NR4A by treating CAR T cells with a small molecule, this strategy might show a strong therapeutic effect against solid cancers such as melanomas.”