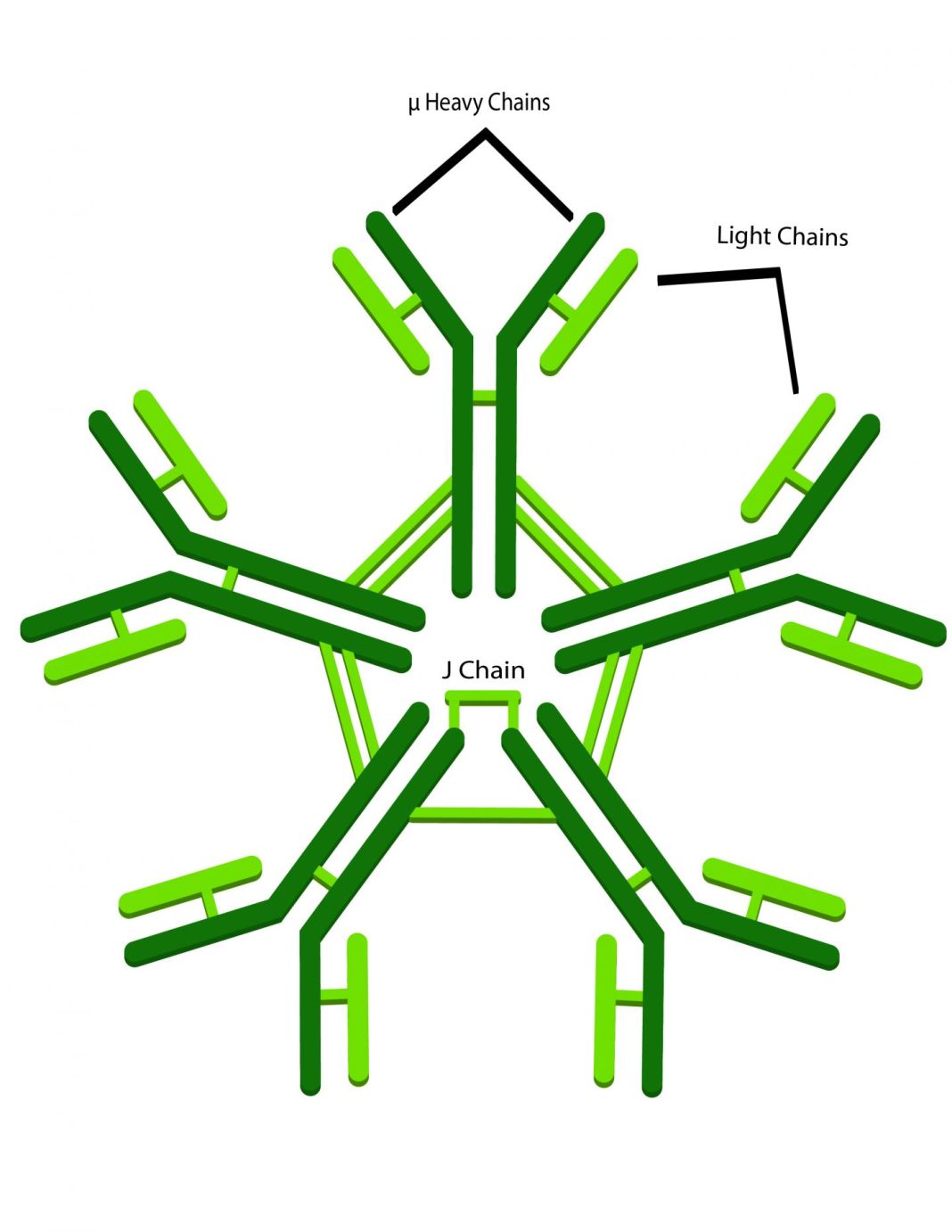

The mammalian immune system produces a range of antibody types in order to protect the host from the daily onslaught of foreign invaders. These various antibody classes typically have well-defined roles and are often temporally produced in response to antigens and often isolated to various tissue types. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) is usually the first antibody class generated in response to infectious agents and is seen in the systemic circulation as well as mucosal fluids. Now, a group of investigators at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute have exploited the high affinity of IgM for antigens, creating a molecule that was effective in preventing HIV infection in rhesus macaques.

Worldwide, an estimated 90% of new cases of HIV-1 are caused through exposure in the mucosal cavities like the inside lining of the rectum or vagina. The researchers utilized the simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) that carries an HIV-1 envelope gene as their model for HIV infection. Moreover, the researchers created recombinant polymeric monoclonal IgM that was generated from the neutralizing monoclonal IgG1 antibody 33C6-IgG1. Findings from the new study were published today in AIDS through an article titled “Anti-HIV IgM protects against mucosal SHIV transmission.”

“IgM is sort of the forgotten antibody,” explained senior study investigator Ruth Ruprecht, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Texas Biomed AIDS Research Program. “Most scientists believed its protective effect was too short-lived to be leveraged as any kind of protective shield against an invading pathogen like HIV-1.”

For the current study, the scientists first treated the primates with a human-made version of IgM, which is naturally produced by plasma cells located under the epithelium (the surface lining of body cavities). Thirty minutes later, the same animals were exposed to SHIV. Four out of the six animals treated this way were fully protected against the virus. The animals were monitored for 82 days.

The research team found that applying the IgM antibodies resulted in what is called immune exclusion. IgM clumped up the virus, preventing it from crossing the mucosal barrier and spreading to the rest of the body. The technique of introducing preformed antibodies into the body to create immunity is known as passive immunization.

“After intrarectal administration, 33C6-IgM prevented viremia in four out of six rhesus macaques after high-dose intrarectal SHIV challenge,” the authors wrote. “Five out of six rhesus macaques given 33C6-IgG1 were protected at a five times higher molar concentration compared with the IgM form; all untreated controls became highly viremic. Rhesus macaques passively immunized with 33C6-IgM with breakthrough infection had notably the early development of autologous neutralizing antibody responses.”

IgM has a high affinity for its antigens and “grabs them very quickly and does not let go,” Dr. Ruprecht noted. “Our study reveals for the first time the protective potential of mucosal anti-HIV-1 IgM. IgM has a five-times higher ability to bind to virus particles compared to the standard antibody form called IgG. It basically opens up a new area of research. IgM can do more than it has been given credit.”

In an accompanying editorial for the journal, Barbara Schmidt, Ph.D., from the Institute for Medical Microbiology and Hygiene in Regensburg, Germany, who was not involved in the current study, concluded that the researchers have “set off a new wave in evaluating the activity of IgM antibodies in neutralizing HIV-1…[and she and her group] have largely broadened the horizon of neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies, which, as single or combined agents, may be used for HIV-1 prevention and treatment.”