In unfortunate news for patients and families of those afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a new multicenter clinical trial, led by investigators at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC), found that the monoclonal antibody-based treatment solanezumab—created to target soluble amyloid protein and reduce plaque formation—did not significantly slow cognitive decline. Findings from the new study were published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, in an article entitled “Trial of Solanezumab for Mild Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease.”

For decades, researchers have proposed that AD is caused by the buildup of a sticky protein called beta-amyloid (Aβ). According to this “amyloid hypothesis,” the protein forms plaques in the brain that damage and eventually destroy brain cells. Solanezumab was designed to reduce the level of soluble amyloid molecules before they aggregate.

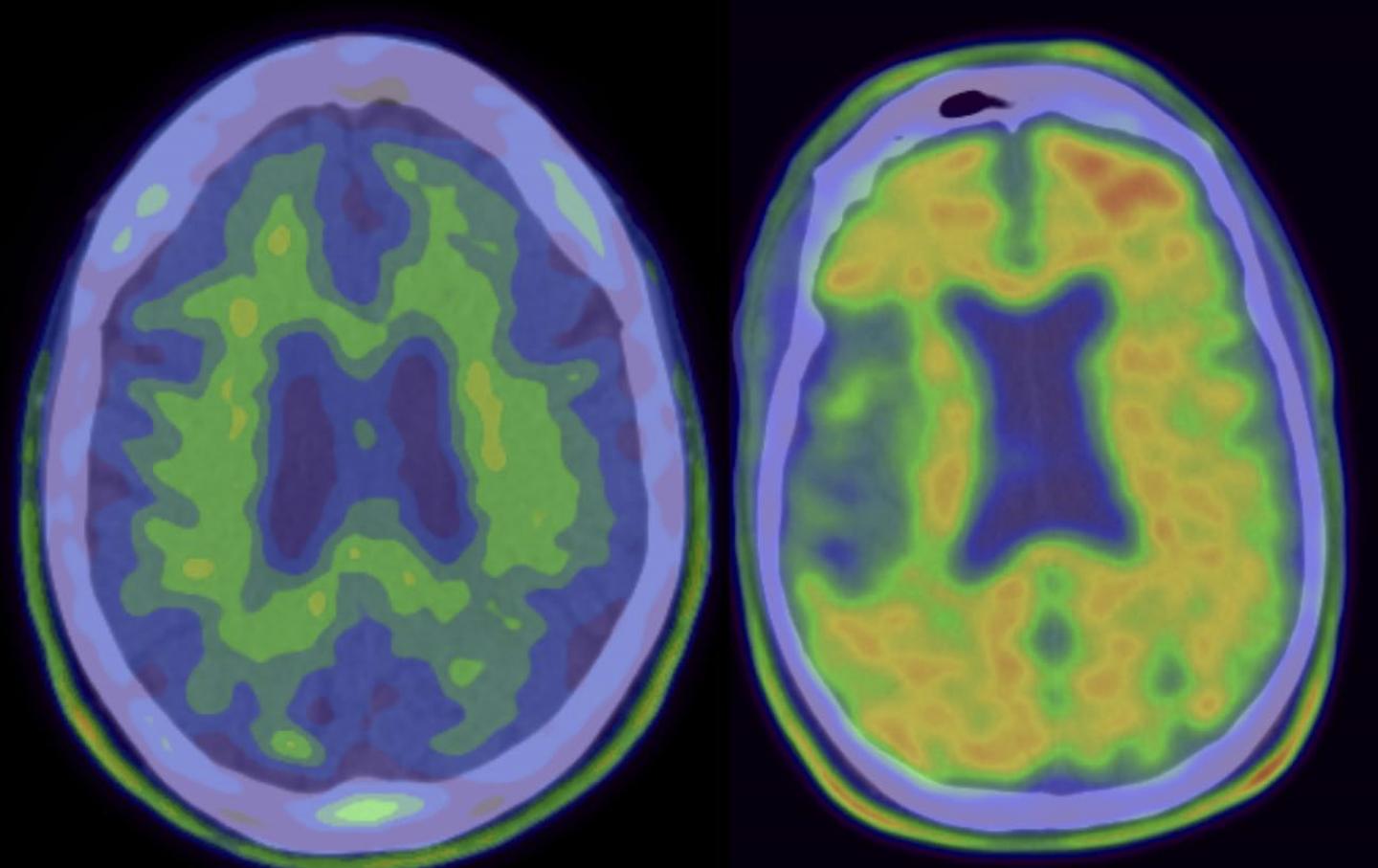

(Left) “Negative” scan, without Alzheimer’s disease pathology. (Right) “Positive” scan of patient eligible for solanezumab clinical trial. [Columbia University Medical Center]

“We conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial involving patients with mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, defined as a Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 20 to 26 (on a scale from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better cognition) and with amyloid deposition shown by means of florbetapir positron-emission tomography or Aβ1-42 measurements in cerebrospinal fluid,” the authors wrote. “Patients were randomly assigned to receive solanezumab at a dose of 400 mg or placebo intravenously every four weeks for 76 weeks. The primary outcome was the change from baseline to week 80 in the score on the 14-item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale.”

A total of 2129 patients with mild dementia due to AD participated in the double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III multicenter trial. This study was the first major AD clinical trial to require molecular evidence of amyloid deposition in the brain for enrollment. While the treatment did have some favorable effects, in the main measure of outcome—measured with a cognitive test called the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale—the researchers did not observe any statistically significant benefit compared with placebo.

“As a result of the failure to reach significance with regard to the primary outcome in the prespecified hierarchical analysis, the secondary outcomes were considered to be descriptive and are reported without significance testing,” the authors remarked. “The change from baseline in the MMSE score was −3.17 in the solanezumab group and −3.66 in the placebo group. Adverse cerebral edema or effusion lesions that were observed on magnetic resonance imaging after randomization occurred in 1 patient in the solanezumab group and in 2 in the placebo group.”

The research team suggested that while it is not certain that this particular strategy or drug could be effective, it is possible that either not enough drug was administered or that the drug needs to be administered earlier in the disease course.

In other studies ongoing at CUIMC, solanezumab is being evaluated in presymptomatic patients at risk of AD. Other AD drugs are also in development and being tested at higher doses.

“Although we are disappointed that this particular drug did not prove successful, the field is benefiting from each study,” concluded lead study investigator Lawrence Honig, M.D., Ph.D., professor of neurology at CUIMC. “There is hope that one of the newer ongoing studies may result in an effective treatment for slowing the course of AD.”