Scientists at the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology and Hubrecht Institute in the Netherlands report organoids and CRISPR-Cas9 allowed them to better understand the tumor biology and biological consequences of different DNA changes of fibrolamellar carcinoma (FLC), a rare type of childhood liver cancer.

The findings are published in Nature Communications in an article titled, “Organoid models of fibrolamellar carcinoma mutations reveal hepatocyte transdifferentiation through cooperative BAP1 and PRKAR2A loss.”

FLC is a rare cancer of the liver that usually affects teens and adults under 40 years old who have no history of liver disease. In the early stages of the disease, affected patients often have no symptoms, so by the time the cancer is found, it may have already spread beyond the liver. Currently, there are no effective treatments for inoperable or metastatic disease. Locally invasive or disseminated disease does not respond to chemotherapy, and unless the tumor can be resected with clear margins, recurrence is common and outcomes are poor.

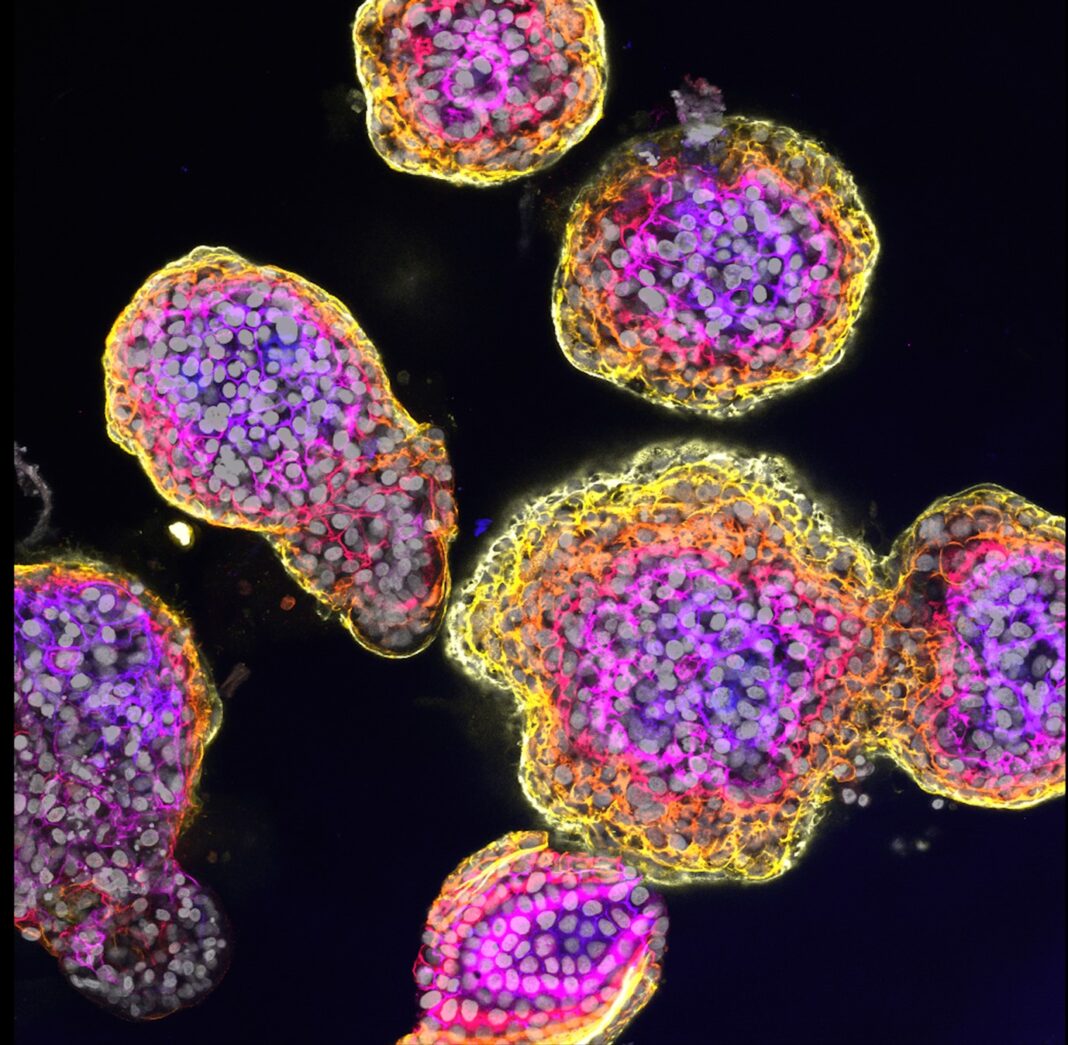

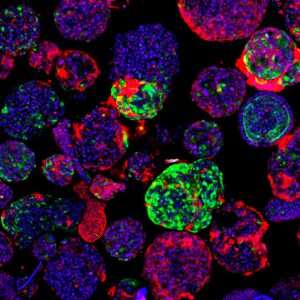

Benedetta Artegiani, PhD, research group leader at the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology, and Delilah Hendriks, PhD, a researcher at the Hubrecht Institute, co-led the study. The researchers and their team constructed the liver organoid models by modifying the protein kinase A (PKA) using CRISPR-Cas9. Changing the function of the different units through genetic changes seems to be crucial for the onset of FLC.

They then introduced another set of DNA changes, also found in patients with FLC. “This second background not only contains a mutation in one of the PKA genes, PRKAR2A, but also in an additional gene called BAP1, said Artegiani. In this case, the organoids presented features typical of an aggressive cancer. This suggests that different genetic FLC backgrounds lead to different degrees of tumor aggressiveness.”

The researchers concluded that although mutations in the PKA genes are crucial, they might not be sufficient for development of FLC. “These findings open the possibility to look for other factors to occur together with PKA mutations in FLC tumors,” added Hendriks. “This could be potentially exploited for possible future therapies for this form of childhood cancer.”

Their findings pave the way for further research on how to better treat this rare cancer type, and understanding the importance of specific gene faults in the initiation of FLC could in the future also help to better understand tumor heterogeneity and response between patients.