Researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSOM) have discovered that breast cancer cells can alter the function of Natural killer (NK) cells in order to spread to other parts of the body. Using several new assays to model metastasis as well as experiments in mice, the researchers found that human and mouse NK cells lose the ability to restrict tumor invasion and instead help cancer cells form new tumors. Their discovery suggests that preventing this reprogramming may stop breast cancer from metastasizing to other tissues, which is a major cause of death in breast cancer patients.

Their study, “Cancer cells educate natural killer cells to a metastasis-promoting cell state,” is published in the Journal of Cell Biology and led by Andrew Ewald, PhD, co-director of the Cancer Invasion and Metastasis Program in the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center and professor of cell biology at JHUSOM.

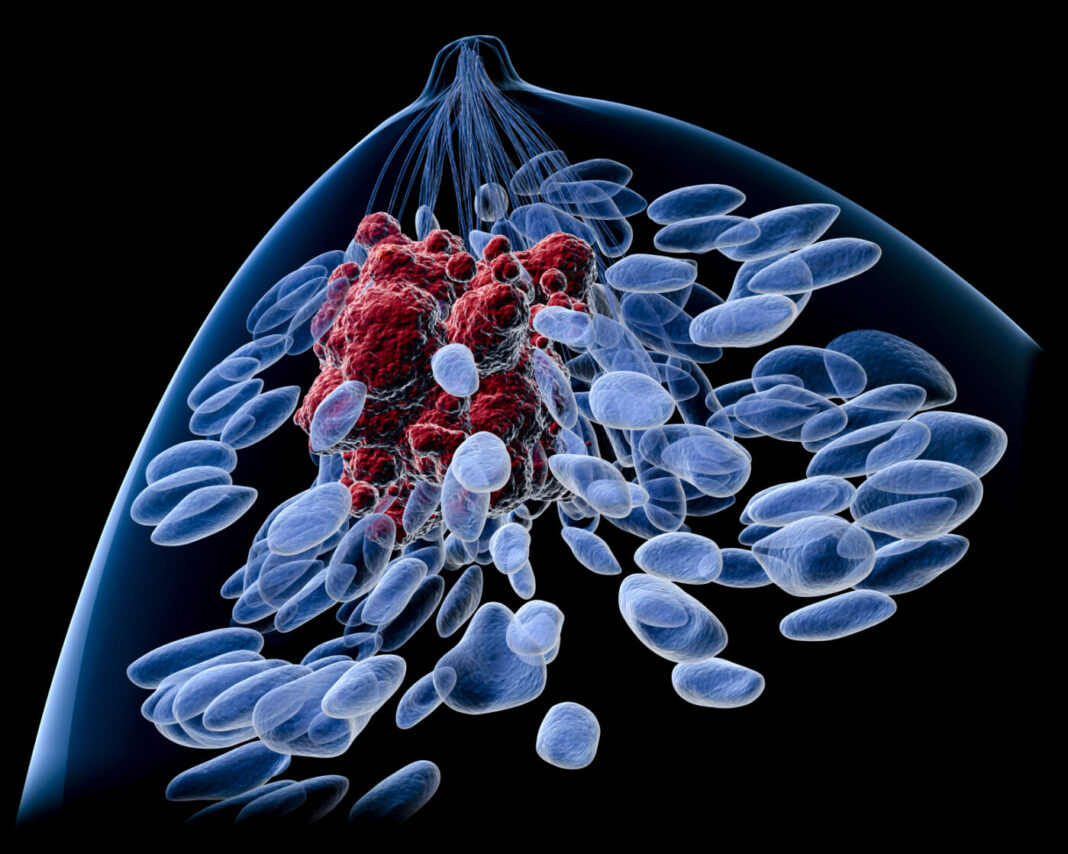

The majority of deaths from breast cancer are not due to the primary tumor itself, but are the result of metastasis to other organs in the body. Metastatic breast cancer can develop when breast cancer cells break away from the primary tumor and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system. The cancer cells are able to travel in the fluids far from the original tumor and then settle and grow in a different part of the body and form new tumors. NK cells are lymphocytes of the innate immune system, involved in the elimination of tumors and microbe-infected cells. However, it is not completely understood how cancer cells escape NK cell surveillance.

The team of researchers discovered although metastasizing breast cancer cells are initially vulnerable to NK cells, they are quickly able to alter the behavior of the NK cells, reprogramming them to promote the later stages of metastasis.

“Using ex vivo and in vivo models of metastasis, we establish that keratin-14+ breast cancer cells are vulnerable to NK cells. We then discovered that exposure to cancer cells causes NK cells to lose their cytotoxic ability and promote metastatic outgrowth. Gene expression comparisons revealed that healthy NK cells have an active NK cell molecular phenotype, whereas tumor-exposed (teNK) cells resemble resting NK cells. Receptor–ligand analysis between teNK cells and tumor cells revealed multiple potential targets,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers found that, after they encounter tumor cells, human and mouse NK cells lose the ability to restrict tumor invasion and instead help cancer cells form new tumors.

At first, the presence of NK cells restricts the growth of a tumor formed in the laboratory. But after 36 hours, the cancer cells reprogram the NK cells and the tumor starts to invade its surroundings. Source: Chan et al., 2020.

NK cells undergo changes when exposed to tumors, turning thousands of genes on and off and expressing different receptor proteins on their surface. The researchers found that antibodies targeting two key receptor proteins on the surface of NK cells, called TIGIT and KLRG1, prevented NK cells from helping breast cancer cells seed new tumors.

“Combinations of DNMT inhibitors with anti-TIGIT or anti-KLRG1 antibodies further reduced metastatic potential. We propose that NK-directed therapies targeting these pathways would be effective in the adjuvant setting to prevent metastatic recurrence,” noted the researchers.

“The synergistic effects of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors with receptor-blocking antibodies suggests a viable clinical strategy to reactivate tumor-exposed NK cells to target and eliminate breast cancer metastases,” explained Isaac Chan, MD, PhD, a medical oncology fellow in Ewald’s laboratory and lead author of the study.

“Combined with our observation that NK cells are abundant early responders to disseminated breast cancer cells, our data provide preclinical rationale for the concept of NK cell-directed immunotherapies in the adjuvant setting for breast cancer patients with high risk of metastatic recurrence,” added Ewald.

Their findings suggest that antibodies targeting NK inhibitory receptors could be effective in eliminating metastatic breast cancer cells, and provide preclinical rationale for the concept of NK cell–directed immunotherapies for breast cancer patients with high risk of metastatic recurrence.