The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) immune system is a key player in the brain’s immunity. However, how CSF immunity is altered with aging or neurodegenerative disease is not fully understood. Now, using single-cell RNA sequencing, Northwestern Medicine researchers have discovered CSF’s role in cognitive impairment. The study provides a new clue to the process of neurodegeneration.

The findings, “Cerebrospinal fluid immune dysregulation during healthy brain aging and cognitive impairment,” are published in the journal Cell.

“CSF contains a tightly regulated immune system,” wrote the researchers. “However, knowledge is lacking about how CSF immunity is altered with aging or neurodegenerative disease. Here, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing on CSF from 45 cognitively normal subjects ranging from 54 to 82 years old. We uncovered an upregulation of lipid transport genes in monocytes with age.”

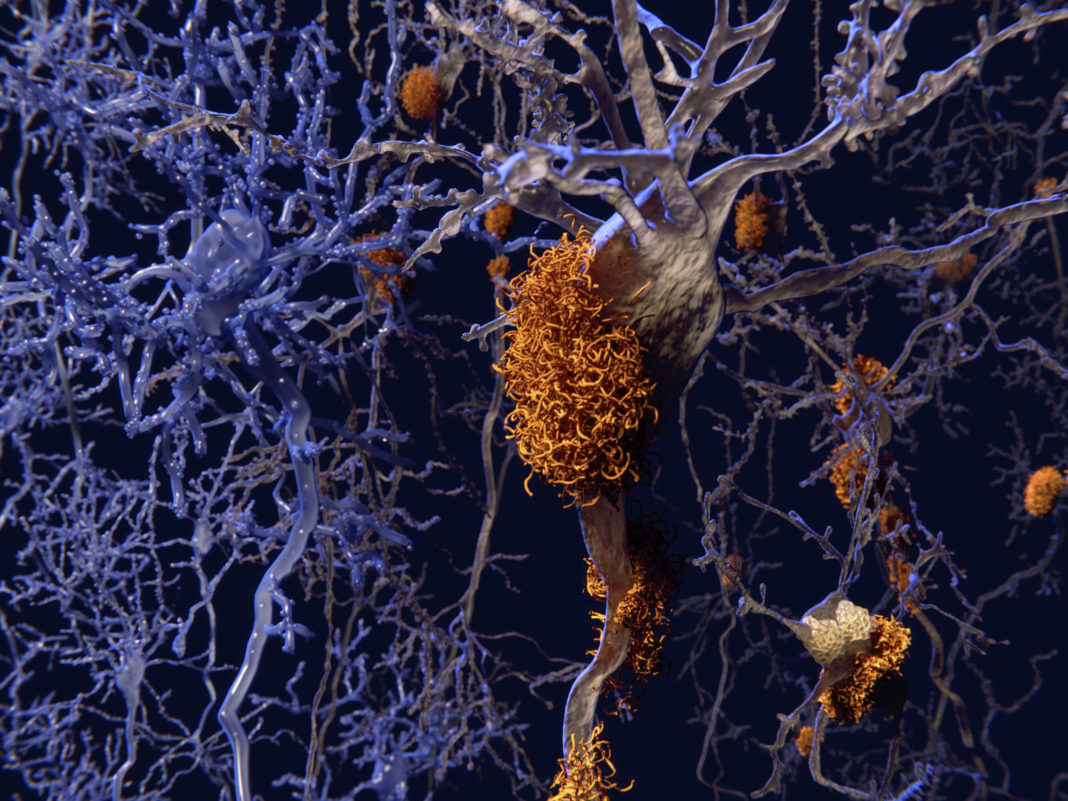

The study found that, as people age, their CSF immune system becomes dysregulated. In people with cognitive impairment, such as those with Alzheimer’s disease, the CSF immune system is drastically different from healthy individuals, the study also discovered.

“We now have a glimpse into the brain’s immune system with healthy aging and neurodegeneration,” said study lead author David Gate, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “This immune reservoir could potentially be used to treat inflammation of the brain or be used as a diagnostic to determine the level of brain inflammation in individuals with dementia.”

“We provide a thorough analysis of this important immunologic reservoir of the healthy and diseased brain,” Gate said. His team is sharing the data publicly, and the results can be searched online.

The first part of the study looked at CSF in 45 healthy individuals aged 54 to 83 years. The second part of the study compared those findings in the healthy group to CSF in 14 adults with cognitive impairment.

The researchers observed genetic changes in the CSF immune cells in older healthy individuals that made the cells appear more activated and inflamed with advanced age.

“The immune cells appear to be a little angry in older individuals,” Gate said. “We think this anger might make these cells less functional, resulting in dysregulation of the brain’s immune system.”

The researchers noted: “In cognitively impaired subjects, downregulation of lipid transport genes in monocytes occurred concomitantly with altered cytokine signaling to CD8 T cells. Clonal CD8 T effector memory cells upregulated C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 6 (CXCR6) in cognitively impaired subjects. The CXCR6 ligand, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 16 (CXCL16), was elevated in the CSF of cognitively impaired subjects, suggesting CXCL16-CXCR6 signaling as a mechanism for antigen-specific T cell entry into the brain.”

The researchers observed the cells had an overabundance of a cell receptor—CXCR6—that acts as an antenna. This receptor receives a signal—CXCL16—from the degenerating brain’s microglia cells to enter the brain.

“It could be the degenerating brain activates these cells and causes them to clone themselves and flow to the brain,” Gate said. “They do not belong there, and we are trying to understand whether they contribute to damage in the brain.”

The researchers are now looking forward to finding a strategy to block the signal or to inhibit the antenna from receiving that signal from the brain. Gate’s laboratory will continue to explore the role of these immune cells in brain diseases like Alzheimer’s. They also plan to expand to other diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).