Under ideal circumstances a cell’s internal environment is too hostile for a pathogen to survive. But certain ingenious pathogens, such as the bacterium Salmonella enterica that causes diarrhea, fever, abdominal cramps, and can at times be fatal, send out a arsenal of proteins (effectors) that hijack a cell’s biological machinery. Salmonella can secrete more than 30 effector proteins into infected cells to hijack nutrients and protect itself but the targets and functions of many of these effectors were unknown, until now.

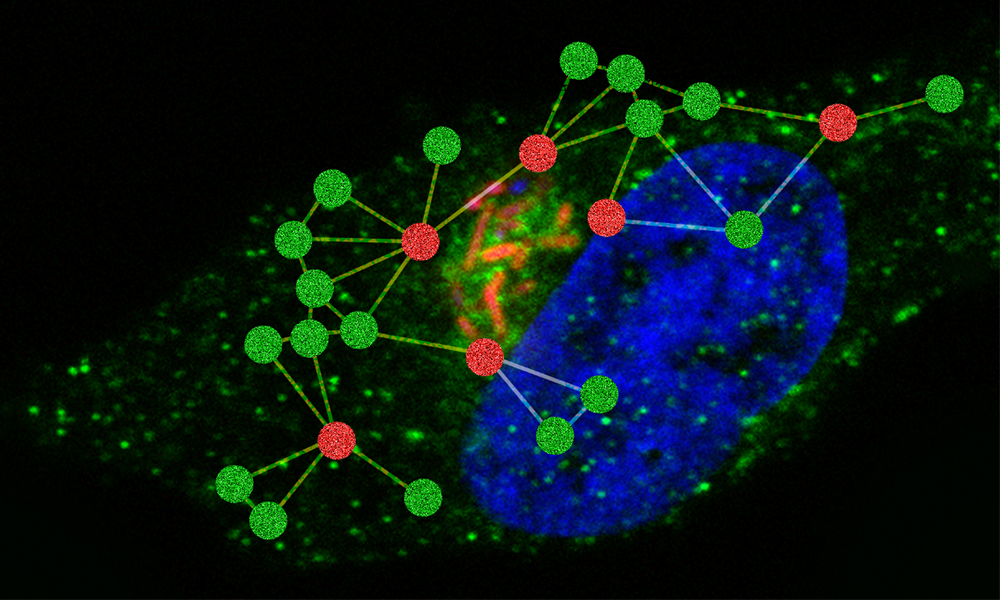

In a new study scientists use quantitative proteomics to precisely map hundreds of interactions between Salmonella effector proteins and host-cell proteins during infection. This host-pathogen interactome reveals that most Salmonella effectors target more than one biological process in the host cell and sometimes multiple Salmonella effectors can converge on same host process in a cell-type-specific manner. The authors also identify at least three molecular mechanisms through which the pathogen subjugates the host cell environment, making it a comfortable home for itself.

These findings, published in the Cell Host & Microbe article, “Global mapping of Salmonella enterica-host protein-protein interactions during infection” were financially supported by EMBL core funding. The study, led by EMBL scientist Athanasios Typas, PhD, is a collaborative effort of scientists from the Imperial College London, U.K., the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Braunschweig, Germany, and Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana that is part of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The study provides novel insights and tools to dissect how pathogens modify host pathways through secreted proteins that can uncover new aspects of pathogen biology and targets to modulate host immune responses.

The EMBL scientists genetically engineered 32 Salmonella strains by adding identifying labels to Salmonella proteins, earmarking one protein in each bacterial strain. These labels act like hooks that the scientists pull at to capture the secreted bacterial proteins along with host cell proteins that they bind to. The researchers then identify the host-pathogen protein interactions using mass spectrometry and validate their findings through biochemical pull-down assays.

The method of modifying effector proteins directly in their host was a technical breakthrough for the study. “The new approach has many benefits over previous experimental strategies. In particular, it characterizes the whole set of host-pathogen protein-protein interactions in cells infected with a live pathogen, closely resembling what occurs in a host organism upon Salmonella infection,” says Joel Selkrig, PhD, research scientist in the Typas group and one of the two lead authors of the study.

The scientists identify 421 previously unknown interactions between Salmonella proteins and proteins in host macrophages and epithelial cells, along with 25 interactions that have been described before.

“We found that multiple Salmonella effectors physically interact with several proteins that the host cell uses to transport cholesterol. This way, cholesterol trafficking can be hijacked for Salmonella’s own purposes,” says Philipp Walch, PhD, who shares first authorship of the study with Selkrig. Salmonella uses cholesterol to modify surrounding membranes, preventing host cell defenses from detecting and destroying it.

The research reveals that other survival strategies that the pathogen uses includes remodeling the network of protein fibers that transport material within the host cell and interfering with the function of a host cell protein that mediates contacts between membranes to facilitate the exchange of lipids and small molecules.

This study bridges a technological gap in host-pathogen studies that were earlier performed under non-physiological conditions, allowing more systematic and unbiased studies of protein-protein interactions in the context of native infections.