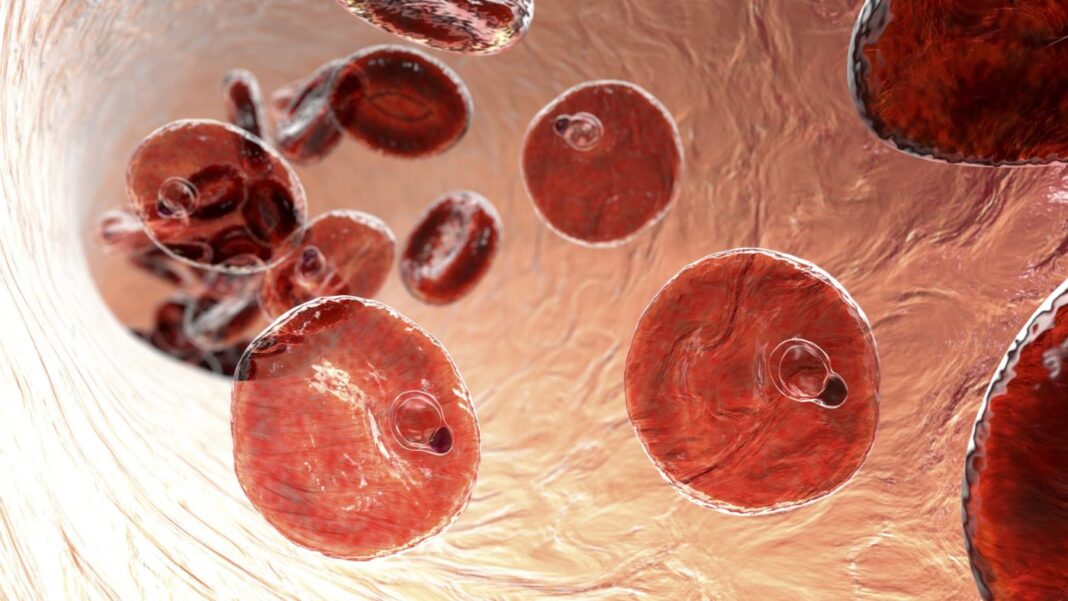

Researchers at Karolinska Institute report they have observed how the immune system acts to protect the body after a malaria infection. Their findings can help in the development of more effective vaccines.

The findings are published in the journal Cell Reports in a paper titled, “Systems analysis shows a role of cytophilic antibodies in shaping innate tolerance to malaria.”

“Natural immunity to malaria develops over time with repeated malaria episodes, but protection against severe malaria and immune regulation limiting immunopathology, called tolerance, develops more rapidly,” write the researchers. “Here, we comprehensively profile the blood immune system in patients, with or without prior malaria exposure, over one year after acute symptomatic Plasmodium falciparum malaria.”

“Our results contribute to a better understanding of how humans fight this serious disease and may help in the development of better vaccines,” said Christopher Sundling, PhD, principal researcher at the department of medicine, Solna, at Karolinska Institute, and last author of the study. “This sheds new light on the question of how the body’s immune system deals with malaria.”

To find out more about how disease tolerance develops, the researchers have investigated immune cells and proteins in blood samples from patients who have been treated for acute malaria infection at Karolinska University Hospital in Solna, Sweden, and have recovered.

“Since we have followed the patients here in Sweden, we can study the natural course of the immune response after a malaria infection, without the risk of a new infection interfering with the results. This cohort has proved to be very valuable for studying the immunology of malaria,” said Anna Färnert, professor of infectious diseases at the department of medicine, Solna, Karolinska Institute, and senior infectious diseases physician at Karolinska University Hospital, Sweden, in whose research group the study was conducted.

The researchers noted a strong inflammatory response from the so-called innate immune system in people who were infected for the first time. In contrast, the people who were re-infected had an ability to suppress the inflammation, Sundling explained.

“In those who have had malaria before, we saw that the early presence of parasite-specific antibodies interrupt the first stages of the inflammation and prevent a certain type of inflammatory T cell from expanding,” Sundling continued.

The researchers concluded that this enhanced control and reduced inflammation points to a potential mechanism for how tolerance is established following repeated malaria exposure.

“This is a weakness of the current vaccine. Understanding how tolerance develops and what happens in the blood stage can help us develop other types of vaccines, which may not fully protect against infection but will lessen the chances of becoming seriously ill. If such a vaccine can enable people to survive the first infections that kill so many, we could save many lives,” said Sundling.