A new Lyme vaccine candidate not only leverages a new modality—mRNA—it also takes aim at some new targets—tick saliva proteins. mRNA vaccines have already become familiar because of the success of mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines. However, tick saliva proteins as vaccine targets are still unfamiliar.

Vaccines typically target pathogens or pathogen elements, not proteins associated with disease vectors. Although there have been promising studies with anti-sandfly proteins that protect hosts against Leishmaniasis, the targeting of the tick proteins that accompany tick bites hadn’t been tried before—that is, before a new study by Yale University researchers.

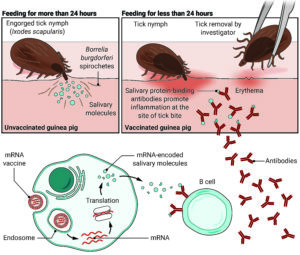

The team, led by epidemiologist Erol Fikrig, MD, developed a 19ISP mRNA vaccine. The “I” in ISP stands for Ixodes scapularis, a tick species that transmits many pathogens that cause human disease, including Borrelia burgdorferi. The “SP” stands for salivary protein. And the “19” stands for the number of SPs encoded by the mRNA vaccine.

To test 19ISP, the researchers immunized guinea pigs with a 19ISP mRNA vaccine and subsequently challenged the guinea pigs with I. scapularis. The results, which appeared in Science Translational Medicine in a paper titled, “mRNA vaccination induces tick resistance and prevents transmission of the Lyme disease agent,” were encouraging.

“Animals administered 19ISP developed erythema at the bite site shortly after ticks began to attach, and these ticks fed poorly, marked by early detachment and decreased engorgement weights,” the article’s authors wrote. “19ISP immunization also impeded B. burgdorferi transmission in the guinea pigs.”

Unlike non-immunized guinea pigs, vaccinated animals exposed to infected ticks quickly developed redness at the tick bite site. And as long as ticks were removed when redness appeared, none of the immunized animals developed Lyme disease. In contrast, about half of the control group became infected with B. burgdorferi after ticks were removed.

When a single infected tick was attached to immunized guinea pigs and not removed, none of them was infected while 60% of control animals did become infected. If three ticks remained attached to the guinea pigs, however, protection waned even in immunized animals. In addition, ticks attached to immunized animals were unable to feed aggressively and dislodged more quickly than those on guinea pigs in the control group.

“The vaccine enhances the ability to recognize a tick bite, partially turning a tick bite into a mosquito bite,” said Fikrig, the Waldemar Von Zedtwitz professor of medicine at Yale. “When you feel a mosquito bite, you swat it. With the vaccine, there is redness and likely an itch so you can recognize that you have been bitten and can pull the tick off quickly, before it has the ability to transmit B. burgdorferi.”

“There are multiple tick-borne diseases, and this approach potentially offers more broad-based protection than a vaccine that targets a specific pathogen,” Fikrig continued. “It could also be used in conjunction with more traditional, pathogen-based vaccines to increase their efficacy.”

Researchers did add a caveat in their findings: In similar experiments, mice, which are unable to acquire natural tick resistance after infection, were not protected against Lyme disease after vaccination. In fact, in contrast to guinea pigs, mice are a natural reservoir for I. scapularis ticks, suggesting that ticks may have evolved to develop ways to specifically feed repeatedly on mice. Another possibility may be that guinea pig skin, like human skin, is more layered than the skin of mice.

Fikrig said more study is needed to discover ways that proteins in saliva can prevent infection. Ultimately, human trials would need to be conducted to assess its efficacy in people.

A new Lyme disease vaccine would certainly be welcome. In the United States, at least 40,000 cases of Lyme disease are reported annually, but the actual number of infections could be 10 times greater. In addition, other tick-borne diseases have also spread in many areas of the country.