Introduced about 100 years to treat drug-resistant epilepsy, and incorporated into a phase of the Atkins diet in the 1970s, the ketogenic diet could have a new role: boosting the immune system. This possibility emerged when research indicated that a ketone metabolite could inhibit inflammatory secretions from immune cells. Since production of this metabolite is induced by the ketogenic diet, which causes ketones to be released into the bloodstream, researchers reasoned that the diet could affect the immune systems response to pathogens such as the flu virus.

The researchers, led by Yale’s Vishwa Deep Dixit, DVM, PhD, and Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, found that if they put mice on a ketogenic diet, the mice were better protected against influenza virus infection. Control mice received standard chow, and experimental mice received special chow purchased from Research Diets—which sounds less appetizing than the human ketogenic diet, which includes meat, fish, poultry, and non-starchy vegetables.

The outcome? Mice fed a ketogenic diet were better able to combat the flu virus than mice fed food high in carbohydrates. According to the researchers, the ketone diet activates a subset of T cells in the lungs not previously associated with the immune system’s response to influenza, enhancing mucus production from airway cells that can effectively trap the virus.

“This was a totally unexpected finding,” said Iwasaki, the Waldemar Von Zedtwitz professor of immunobiology and molecular, cellular, and developmental biology, and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The research project was the brainchild of two trainees—one working in Iwasaki’s lab and the other with Visha Deep Dixit, the Waldemar Von Zedtwitz professor of comparative medicine and of immunobiology. Ryan Molony worked in Iwasaki’s lab, which had found that immune system activators called inflammasomes can cause harmful immune system responses in their host. Emily Goldberg worked in Dixit’s lab, which had shown that the ketogenic diet blocked formation of inflammasomes.

The project was detailed in a paper (“Ketogenic diet activates protective γδ T cell responses against influenza virus infection”) that appeared November 15 in the journal Science Immunology.

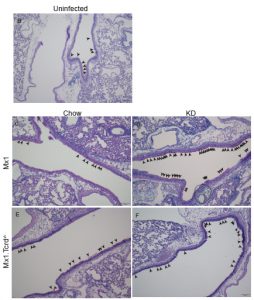

“Ketogenic diet (KD) feeding resulted in an expansion of γδ T cells in the lung that improved barrier functions, thereby enhancing antiviral resistance, the article’s authors wrote. “Expansion of these protective γδ T cells required metabolic adaptation to a ketogenic diet because neither feeding mice a high-fat, high-carbohydrate diet nor providing chemical ketone body substrate that bypasses hepatic ketogenesis protected against infection. Therefore, KD-mediated immune-metabolic integration represents a viable avenue toward preventing or alleviating influenza disease.”

Essentially, the researchers showed that mice fed a ketogenic diet and infected with the influenza virus had a higher survival rate than mice on a high-fat, high-carb normal diet. Specifically, the researchers found that the ketogenic diet triggered the release of γδ T cells, immune system cells that produce mucus in the cell linings of the lung—while the high-carbohydrate diet did not. Also, the separate provision of chemical ketones failed to offer protection.

When mice were bred without the gene that codes for γδ T cells, the ketogenic diet provided no protection against the influenza virus.

“This study,” declared Dixit, “shows that the way the body burns fat to produce ketone bodies from the food we eat can fuel the immune system to fight flu infection.”