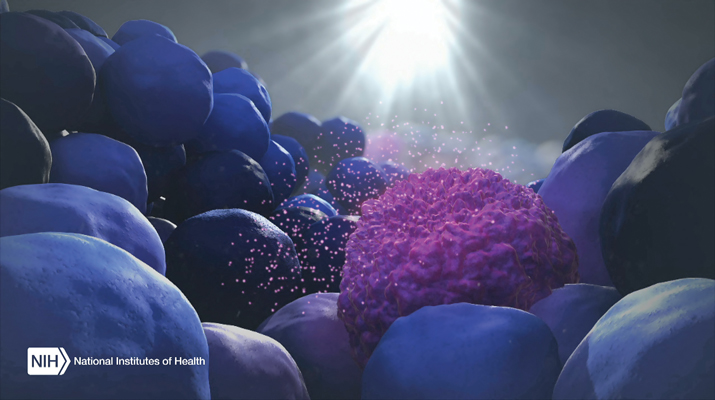

![Doctors may soon be able to detect and monitor a patient's cancer with a simple blood test, reducing or eliminating the need for more invasive procedures. [NIH]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Feature_pic__Exosomes_Blue1123445712-1.jpg)

Doctors may soon be able to detect and monitor a patient’s cancer with a simple blood test, reducing or eliminating the need for more invasive procedures. [NIH]

The goal of many precision medicine initiatives is not only to personalize diagnostic testing for each patient but also to simplify testing procedures as much as possible. Well, a simple blood draw to detect and monitor patient’s cancer is about as straightforward as molecular diagnostics gets. This approach—called liquid biopsy—was designed to search for circulating DNA or cells that have been shed by a tumor within the body. Typically, the recovered DNA is sequenced to detect a genetic biomarker associated with a particular cancerous tissue.

Now, investigators at Purdue University Center for Cancer Research have just published data on a new approach that identifies a series of proteins in blood plasma that, when elevated, signify that the patient has cancer. The new study, which was published recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in an article entitled “Phosphoproteins in Extracellular Vesicles as Candidate Markers for Breast Cancer,” relies on the analysis of microvesicles and exosomes in blood plasma. Moreover, while the current work was done with samples from breast cancer patients, the scientists believe it’s possible the method could work for any cancer and other types of diseases.

“There are so many types of cancer, even multiple forms for different types of cancer, that finding biomarkers has been discouraging,” explained senior study author W. Andy Tao, Ph.D., professor of biochemistry and member of the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research. “This is definitely a breakthrough, showing the feasibility of using phosphoproteins in blood for detecting and monitoring diseases.”

Protein phosphorylation, the addition of a phosphate group to a protein, can lead to cancer cell formation, and phosphoproteins have been a prime candidate as cancer biomarkers. Until now, however, scientists weren't sure identification of phosphoproteins in blood was possible because the liver releases phosphatase enzymes into the bloodstream that dephosphorylate proteins.

Dr. Tao and his colleagues found nearly 2400 phosphoproteins in a blood sample and identified 144 that were significantly elevated in cancer patients. The study compared 1-mL blood samples from 30 breast cancer patients with six healthy controls.

The investigators used high-speed centrifugation to isolate microvesicles and exosomes from the collected blood samples. These particles, which are released from cells and enter the bloodstream, play a role in intercellular communication and are thought to be involved in metastasis—spreading cancer from one area to another within the body. Additionally, microvesicles and exosomes encapsulate phosphoproteins, which Dr. Tao and his colleagues were able to identify using mass spectrometry.

“Extracellular vesicles, which include exosomes and microvesicles, are membrane-encapsulated. They are stable, which is important,” Dr. Tao noted. “The samples we used were 5 years old, and we were still able to identify phosphoproteins, suggesting this is a viable method for identifying disease biomarkers.”

A simple blood test for cancer would be far less invasive than scopes or biopsies that remove tissue—the foundational basis for liquid biopsies. A doctor could also regularly test a cancer patient's blood to understand the effectiveness of treatment and monitor patients after treatment to see if the cancer is returning.

“There is currently almost no way to monitor patients after treatment,” remarked Dr. Tao. “Doctors have to wait until cancer comes back.”

Timothy Ratliff, Ph.D., director of the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research concluded that “the vesicles and exosomes are present and released by all cancers, so it could be that there are general patterns for cancer tissues, but it's more likely that Andy will develop patterns associated with different cancers. It's exciting. Early detection of cancer is key and has been shown to clearly reduce the death rate associated with the disease.”