Overly thick and sticky mucus contributes to cystic fibrosis and several other diseases, including chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. All these diseases involve the lungs, but thick and sticky mucus can also be a problem elsewhere—the intestine. Curiously, the molecular mechanism that accounts for thick mucus in the lungs also leads to thick mucus in the intestine, contributing to gluten intolerance and a form of celiac disease. This molecular connection, which emerged in a study of cystic fibrosis and celiac disease, suggests that drugs already developed for cystic fibrosis could help drug developers devise new treatments to resolve gluten intolerance.

The study, led by scientists based in Italy and France, appeared November 29 in The EMBO Journal, in an article titled, “A pathogenic role for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in celiac disease.” This study highlights the role of mutations of the gene coding for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), an anion channel pivotal for epithelial adaptation to cell‐autonomous or environmental stress. When CFTR fails in cystic fibrosis, it causes mucus to accumulate in patients’ lungs and intestine.

But why explore a connection to gluten intolerance and celiac disease? Well, the scientists realized that the prevalence of celiac disease is about three times higher in patients who also suffer from cystic fibrosis. “This co-occurrence made us wonder if there is a connection between the two diseases at the molecular level,” said Luigi Maiuri of the University of Piemonte Orientale in Novara and San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, Italy, who led the research together with Valeria Raia of the University Federico II of Naples, Italy; and Guido Kroemer of the University of Paris Descartes, France.

CFTR malfunction, the scientists noted, triggers several reactions in the lungs and other organs by activation of the immune system. These effects are very similar to the responses triggered by gluten in celiac patients. Maiuri, Kroemer, and their colleagues took a closer look at the molecular underpinnings of these similarities.

“Here, we show that the α‐gliadin‐derived LGQQQPFPPQQPY peptide (P31–43) inhibits the function of CFTR,” the authors of the current study wrote. “P31–43 binds to, and reduces ATPase activity of, the nucleotide‐binding domain‐1 (NBD1) of CFTR, thus impairing CFTR function. This generates epithelial stress, tissue transglutaminase and inflammasome activation, NF‐κB nuclear translocation, and IL‐15 production, that all can be prevented by potentiators of CFTR channel gating.”

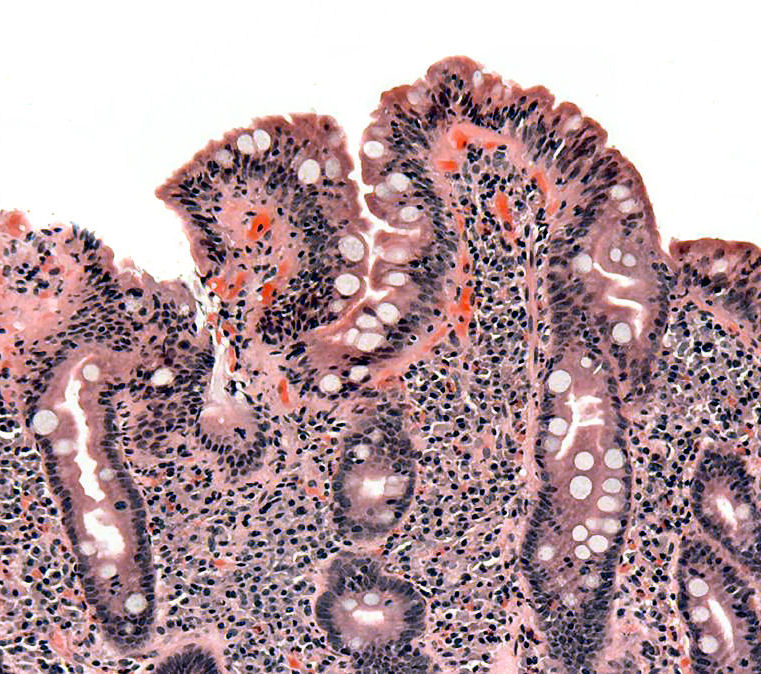

Gluten is difficult to digest, so that relatively long peptides enter the intestine. Using human intestinal cell lines that are sensitive to gluten, the researchers found that one specific peptide, P31-43, directly binds to CFTR and impairs its function. This interaction triggers cellular stress and inflammation, suggesting that CFTR plays a central role in mediating gluten sensitivity in celiac patients.

Moreover, the interaction between P31-43 and CFTR can be inhibited by a potentiator of CFTR, called VX-770. When intestinal cells or tissue samples collected from celiac disease patients were pre-incubated with VX-770 before being exposed to P31-43, the peptide did not elicit an immune reaction. Thus, VX-770 protects gluten-sensitive epithelial cells from the detrimental effect of gluten. In addition, the researchers found that VX-770 could protect gluten-sensitive mice from gluten-induced intestinal symptoms.

“The CFTR potentiator VX‐770 attenuates gliadin‐induced inflammation and promotes a tolerogenic response in gluten‐sensitive mice and cells from celiac patients,” the article’s authors detailed. “Our results unveil a primordial role for CFTR as a central hub orchestrating gliadin activities and identify a novel therapeutic option for celiac disease.”

There is, as yet, no cure for celiac disease; the only therapeutic strategy is to keep a strict diet. However, the current study is a promising step towards the development of a treatment. It suggests that CFTR potentiators, which have been developed to treat cystic fibrosis, may also be explored as a starting point for the development of a remedy for celiac disease.