Targeted immune system–modifying therapies have seen a massive spike in attention recently—as these immunotherapies have been successful in helping patients that were intractable to other, more common treatments. Although successful, immunotherapies do not work for everyone and investigators continually seek to identify which patient populations to target. Now, researchers supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) have discovered how to better predict who will respond to the therapy and who will not. Findings from the new study were published today in Nature Medicine, in an article entitled “A Transcriptionally and Functionally Distinct PD-1+ CD8+ T Cell Pool with Predictive Potential in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with PD-1 Blockade.”

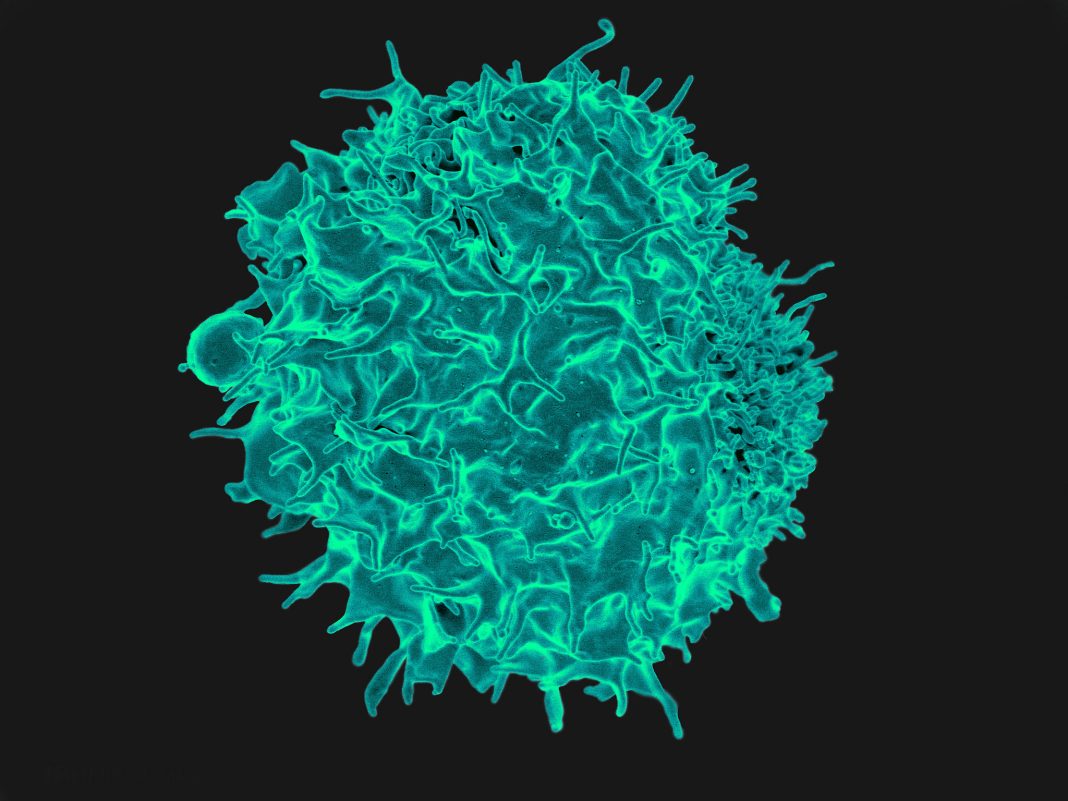

Immunotherapy changes a patient's immune system to allow it to attack cancer cells and either destroy them or at least keep them from growing. The key is a protein known as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), which sits on the surface of human immune cells. Until recently, PD-1 was regarded as their Achilles heel because cancer cells attach to the protein, thereby protecting themselves from immune system attack.

“It's as though the tumor were wearing camouflage,” noted senior study investigator Alfred Zippelius, M.D., deputy head of medical oncology at the University Hospital Basel. Immunotherapy blocks the attachment site, so the immune cells can “see” the cancer again.

In the new study, Dr. Zippelius and his colleagues show that immune cells with the most PD-1 are best able to detect tumors. Additionally, these PD-1–rich cells secrete a signaling compound that attracts additional immune cells to help fight the cancer. “Therefore, these patients have a better chance of responding to immunotherapy,” explained lead study investigator Daniela Thommen, M.D., Ph.D., who is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam.

“We compared transcriptional, metabolic and functional signatures of intratumoral CD8+ T lymphocyte populations with high (PD-1T), intermediate (PD-1N) and no PD-1 expression (PD-1–) from non-small-cell lung cancer patients,” the authors wrote. “PD-1T T cells showed a markedly different transcriptional and metabolic profile from PD-1N and PD-1– lymphocytes, as well as an intrinsically high capacity for tumor recognition. Furthermore, while PD-1T lymphocytes were impaired in classical effector cytokine production, they produced CXCL13, which mediates immune cell recruitment to tertiary lymphoid structures.”

The authors continued, stating that “Strikingly, the presence of PD-1T cells was strongly predictive for both response and survival in a small cohort of non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with PD-1 blockade.”

At present, still, only a fraction of patients respond to immunotherapy. “If we could tell from the outset who the therapy will work for, we could increase the success rate. That would reduce side effects and also lower costs”, stated Dr. Zippelius.

The new findings will enable researchers to develop a practical tool that could ultimately help doctors to decide which patients will benefit from a simple immunotherapy approach and which will require more intensive treatment—for example, a combination of chemotherapy and radiation. For that to happen, researchers must first find a way of distinguishing patients based on the amount of PD-1 in their immune cells.

“What's revolutionary about it is that some patients may remain cured after years of treatment—even in the case of tumors that have otherwise proved resistant to therapy,” Dr. Zippelius concluded.