Unique signatures of DNA methylation and histone retention associated with obesity, and kidney and prostate diseases, were seen in the third generation following brief periods of glyphosate exposure, reports a new study on Sprague Dawley rat models. These inheritable signature biomarkers, the researchers noted, if replicated in human studies, can result in epigenetic diagnostics that will facilitate preventative medicine in future generations.

Glyphosate is widely used in agriculture and therefore commonly found in human food. Earlier studies show glyphosate has a short half-life and breaks down in the body quickly. Despite these indications of limited toxicity, Skinner’s team and other animal studies confirm that phenotypic effects from glyphosate can be inherited by subsequent generations.

“While we can’t fix what’s wrong in the individual who is exposed, we can potentially use this to diagnose if someone has a higher chance of getting kidney or prostate disease later in life, and then prescribe a therapeutic or lifestyle change to help mitigate or prevent the disease,” said Skinner, who is also a professor of biological sciences at Washington State University.

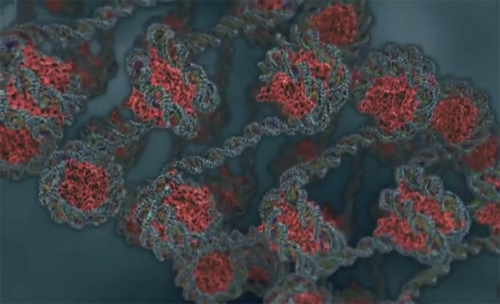

Differential DNA methylation regions (DMRs) and differential histone retention (DHRs) constitute molecular factors and processes around DNA that regulate genome activity without changing DNA sequences and are called epimutations. These epimutations mediate epigenetic inheritance of disease and other phenotypic variations. The DMR and DHR associated genes were identified and correlated with established, disease-specific genes.

Less than 1% of the population of patients suffering from common human diseases such as prostate disease, kidney disease, obesity, and multiple disease pathologies can be associated with causative genetic mutations. In contrast, several studies including this current report reveal a higher frequency of changes in epigenetic sites, epimutation biomarkers, in individuals with these diseases. By the time third- and fourth-generation rats whose predecessors had been briefly exposed to the glyphosate were middle-aged, 90% had one or more of the three diseases investigated, a dramatically higher rate than the control group.

The study shows that for third-generation males (great-grandsons) with these diseases, the number of regions with altered DNA methylation exceeded 200, with little overlap among prostate, kidney, obesity, and multiple disease pathologies, at a strict statistical threshold. At a more relaxed statistical threshold, 30–50% of the regions with changed methylation status overlap among the different diseases investigated. This suggests some epimutations are common among these diseases whereas a unique set of disease-specific biomarkers show disease-specific susceptibility.

The team further probed into epigenetic changes in rat sperms caused by glyphosate. Despite the replacement of histones by protamines to compact DNA into the head of mature sperm, some histone retention sites are conserved in sperm. Skinner and his colleagues found that glyphosate promotes the inheritance of differential histone retention (DHR) in sperm over generations. This is the first report of the association for these sperm DHRs with specific diseases. Therefore, sperm histone retention can potentially be used as a biomarker for specific diseases, the authors noted.

The goal is to replicate these studies in humans and develop epigenomic diagnostic tests. But a major obstacle to accomplishing this is the nearly ubiquitous presence of glyphosate in our diets.

“Right now, it’s very difficult to find a population that is not exposed to glyphosate to have a control group for comparison,” Skinner said.

Skinner added, “We need to change how we think about toxicology. Today worldwide, we only assess direct exposure toxicology. We don’t consider subsequent generational toxicity. We do have some responsibility to our future generations.”