Scientists say that research using zebrafish has revealed how key brain cells that are damaged in people with Parkinson’s disease can be regenerated. The University of Edinburgh-led team reports (“Regeneration of dopaminergic neurons in adult zebrafish depends on immune system activation and differs for distinct populations”) in the Journal of Neuroscience that their findings offer clues that could one day lead to treatments for the neurological condition, which causes movement problems and tremors.

Parkinson’s occurs when specialized nerve cells in the brain are destroyed. These cells are responsible for producing dopamine. When these cells die, or become damaged, the loss of dopamine causes body movements to become impaired. Once these cells are lost from the human brain, they cannot be repaired or replaced.

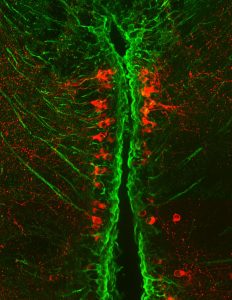

In zebrafish, however, dopamine-producing nerve cells are constantly replaced by dedicated stem cells in the brain, the researchers found. The researchers found that the immune system plays a key role in this process. In some regions of a zebrafish’s brain, the process does not work, however.

“Adult zebrafish, in contrast to mammals, regenerate neurons in their brain, but the extent and variability of this capacity is unclear. Here we ask whether loss of various dopaminergic neuron populations is sufficient to trigger their functional regeneration. Both sexes of zebrafish were analyzed. Genetic lineage tracing shows that specific diencephalic ependymo-radial glial progenitor cells (ERGs) give rise to new dopaminergic (Th+) neurons. Ablation elicits an immune response, increased proliferation of ERGs and increased addition of new Th+ neurons in populations that constitutively add new neurons, e.g. diencephalic population 5/6. Inhibiting the immune response attenuates neurogenesis to control levels,” write the investigators.

“Boosting the immune response enhances ERG proliferation, but not addition of Th+ neurons. In contrast, in populations in which constitutive neurogenesis is undetectable, e.g. the posterior tuberculum and locus coeruleus, cell replacement and tissue integration are incomplete and transient. This is associated with loss of spinal Th+ axons, as well as permanent deficits in shoaling and reproductive behavior. Hence, dopaminergic neuron populations in the adult zebrafish brain show vast differences in regenerative capacity that correlate with constitutive addition of neurons and depend on immune system activation.”

“We were excited to find that zebrafish have a much higher regenerative capacity for dopamine neurons than humans,” says Thomas Becker, PhD, of the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Discovery Brain Sciences. “Understanding the signals that underpin regeneration of these nerve cells could be important for identifying future treatments for Parkinson’s disease.”