A shared characteristic across most higher mammals is our ability to recognize faces. In humans, even in the absence of various cues and context the brain fills in the gaps and can often “see” faces where none exist. Conversely, a neurological disorder such as prosopagnosia, or face blindness, is characterized by difficulty in facial recognition—sometimes as severe as not being able to discriminate a face from other objects. Certainly, a very different world than the one most of us know, where different faces convey essential information. For instance, most of us can recognize a celebrity’s face even if it only appears for a fraction of second. Moreover, many of us can sense the mood of a significant other just based on facial expression and we can establish whether a person is trustworthy by just looking at their face. Yet, despite intensive research, how the brain achieves all these behaviors is still a great mystery.

However now, investigators at Bar-Ilan University, Israel and the Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital, France have released data identifying, for the first time, the neurons in the human visual cortex that selectively respond to faces. Findings from this new study were published recently in Neurology through an article titled “Face-selective neurons in the vicinity of the human fusiform face area.”

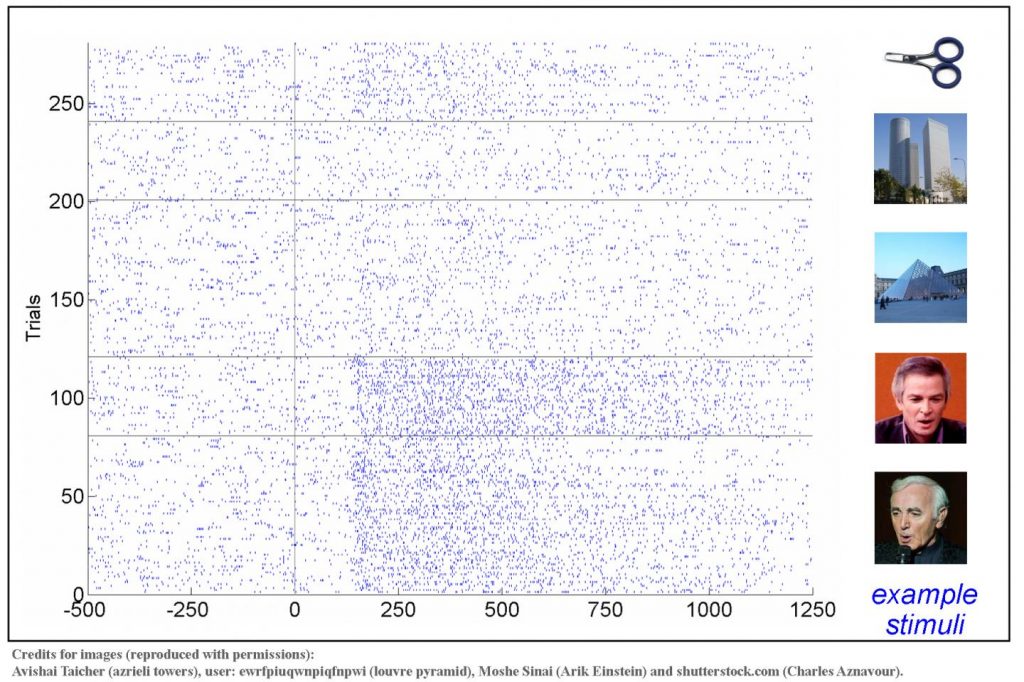

“In the early 1970s Prof. Charles Gross and colleagues discovered the neurons in the visual cortex of macaque monkeys that responded to faces,” noted lead study investigator and the paper’s lead author, Vadim Axelrod, PhD, principle investigator and head of the Consciousness and Cognition Laboratory at the Gonda (Goldschmied) Multidisciplinary Brain Research Center at Bar-Ilan University. “In humans, face-selective activity has been extensively investigated, mainly using noninvasive tools such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electrophysiology (EEG),” explained Axelrod. “Strikingly, face-neurons in posterior temporal visual cortex have never been identified before in humans. In our study, we had a very rare opportunity to record neural activity in a single patient while micro-electrodes were implanted in the vicinity of the Fusiform Face Area—the largest and likely the most important face-selective region of the human brain.”

Interestingly, some of the best-known neurons that respond to faces have been the so-called “Jennifer Aniston cells,” the neurons in the medial temporal lobe that respond to different images of a specific person (i.e., Jennifer Aniston in the original study published in Nature by Quiroga and colleagues in 2005).

“But the neurons in the visual cortex that we reported here are very different from the neurons in the medial temporal lobe,” Axelrod added. “First, the neurons in the visual cortex respond vigorously to any type of face, regardless of the person’s identity. Second, they respond much earlier. Specifically, while in our case, a strong response could be observed within 150 milliseconds of showing the image, the ‘Jennifer Aniston cells’ usually take 300 milliseconds or more to respond.”

The researchers were excited by their findings and these new study results provide unique insights into human brain functioning at the cellular level during face processing. These findings also help bridge the understanding of face mechanisms across species (i.e., monkeys and humans).

“It is really exciting that after almost half a century since the discovery of face-neurons in macaque monkeys, it is now possible to demonstrate similar neurons in humans,” Axelrod concluded.