Studies by Salk Institute scientists have suggested how high-fat diets may fuel the early development of colorectal cancer in people who have a common genetic mutation. Findings from the studies in mouse models and human cells, and reported in Cell, indicate that a high-fat diet and genetics combine to change bile acid balance in the gut, which in turn impacts on bile acid hormonal signaling to stem cells and lets potentially cancerous cells survive. The team, headed by Ronald Evans, PhD, who holds Salk’s March of Dimes chair in molecular and developmental biology, in addition, showed that chemically activating farsenoid X receptor (FXR) signaling in the gut counteracted the effect of unbalanced bile acids in both mouse organ models and in human colon cancer cell lines.

The studies hint that high-fat diets could help to explain why deaths from colorectal cancer in people under 55 years of age are on the increase, even though overall cancer death rates are falling. “It could be that when you’re genetically prone to get cancer, something like a high-fat diet is a second hit,” added Ruth Yu, PhD, a staff researcher at the Gene Expression Laboratory at Salk, and co-author of the team’s published paper. “This study provides a new way to lower inflammation, restore intestinal health, and to dramatically reduced tumor progression,” suggested Evans, who is also director of the Gene Expression Laboratory, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. The researchers’ published paper is titled, “FXR Regulates Intestinal Cancer Stem Cell Proliferation.”

High-fat diets, lack of exercise, obesity, diabetes, and high serum levels of toxic bile acids are all risk factors for colorectal cancer (CRC). The gastrointestinal tract contains a population of intestinal stem cells (ISCs) that replenish the cells lining the gut, but this process can be disrupted by diet, the team pointed out. “Dietary fatty acids have been implicated in enhancing the self-renewal capacity of ISCs and progenitor cells, as well as the tumor-initiating potential of cancer stem cells (CSCs).”

Mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, which normally acts as a tumor suppressor in these stem cells, can remove the gene’s control on stem cell replication and allow them to become cancerous, the authors explained. In fact, most CRC patients carry APC mutations. “Although the majority of CRC cases are sporadic, ~85% of patients have mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, a crucial negative regulator of Wnt signaling,” the team wrote.

Work in Evans’ lab has for the last 40 years been investigating the roles of the 30 or so bile acids that help to digest food and absorb cholesterol, fats, and fat-soluble nutrients. The researchers had discovered that bile acids send hormonal signals to gastrointestinal stem cells via the FXR receptor, which acts as “the master regulator of BA homeostasis, governing synthesis, efflux, influx, and detoxification throughout the gut-liver axis,” they wrote. The researchers’ new work builds on their previous findings, and demonstrates how high-fat diets can impact on that hormonal signaling.

Work by Salk postdoctoral fellow Ting Fu, PhD, who is first author on the published paper, focused on a mouse model with an APC mutation that develops early colorectal cancer. She found that levels of bile acids that interact with FXR increased at the same time as the animals started to develop cancer. The presence of additional bile acids further speeded cancer progression. “We saw a very dramatic increase in cancer growth correlated to bile acid,” said Michael Downes, PhD, a senior staff scientist at Salk and co-corresponding author of the study. “Our experiments showed that maintaining a balance of bile acids is key to reducing cancer growth.”

Further in vivo studies suggested that T-βMCA was the main driver of CRC progression. “These findings imply that T-βMCA can effectively recapitulate the ability of HFD to promote CRC progression,” they added. “We knew that high-fat diets and bile acids were both risk factors for cancer, but we weren’t expecting to find they were both affecting FXR in intestinal stem cells,” noted Annette Atkins, PhD, a staff researcher at Salk and co-author of the study.

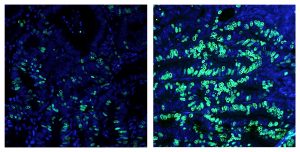

The mutant APC mouse model commonly develops adenomas that only slowly, if at all, develop into malignant adenocarcinomas. This process of adenoma to adenocarcinoma conversion was found to be much faster in animals fed a high-fat diet. The researchers then used a Salk-developed FXR agonist molecule called FexD, to activate the receptor. Administration of FexD reversed the effects of unbalanced bile acids in mouse organoids and in human colon cancer-derived organoids. FexD administration also delayed tumor progression in the mouse model of CRC, and prolonged survival. “… selective activation of intestinal FXR retards the progression of adenomas and adenocarcinomas,” they stated. “… survival studies revealed profound improvements upon FexD treatment.”

The researchers concluded that FXR acts as “a point of convergence of heredity (H) and environmental (E) risk factors for CRC … Our studies demonstrate that the APC mutation and high-fat diet independently and cooperatively increase the BA pool that results in the repression of FXR signaling in intestinal stem cells.”