New research from EPFL, Switzerland, offers fresh insights into how some gut bacteria protect themselves against deadly cholera infection opening doors for the design of probiotic strains that can successfully combat the pathogen’s cunning killing strategies. Unfortunately, cholera still kills up to 143,000 people each year and infects up to four million others, according to the World Health Organization.

How Cholera kills

The bacterium Vibrio cholerae usually enters the body through contaminated drinking water. It colonizes the gut’s inner surface and releases a potent toxin that disrupts the delicate balance of electrolytes across the gut’s wall. This causes acute watery diarrhea. If left untreated, patients die from severe dehydration.

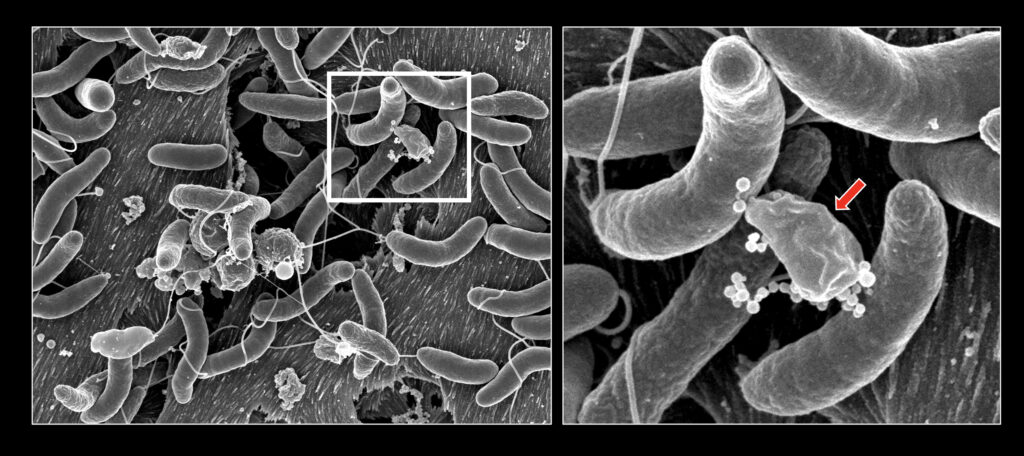

Vibrio cholerae’s rampage in the human gut does not stop at disrupting its ionic balance. It uses a shrewd “interbacterial killing device” called the ‘type VI secretion system’ or T6SS to inject toxins into neighboring cells to eliminate competition and establish social dominance in the complex microbial communities that reside amicably in the human gut.

And it’s not just that. The bacteria that Vibrio cholera’s T6SS system kills, release their DNA which is promptly assimilated by the killer to quickly evolve into super strains with deadlier virulence and antibiotic resistance.

Like all crafty killing machines, bacteria like Vibrio cholerae that use T6SS remember to protect themselves against their own weapon to prevent self-intoxication. They do this by producing immune proteins that block the toxic effects of their own T6SS.

Model malady

All invading pathogens that infect the gut must dominate resident harmless bacteria—commensal species. Pathogens accomplish this using various strategies that range from competing with commensal microorganisms for food, nutrients, and space, to directly killing them.

Identifying the right model system in which to study how Vibrio cholerae interacts with the gut microbiome has been difficult. Usually, infectious disease researchers use adult animals as model systems. But Vibrio cholerae is rather selective in infecting human adults. It colonizes other adult animals poorly.

This compels scientists to use juvenile animal models to study the mechanisms of Vibrio cholerae infection. But the guts of young animals do not house the mature microbiomes of adult animals with which scientists seek to understand Vibrio cholerae’s interactions.

Therefore, largely due to the lack of a proper model, the interactions between commensal microorganisms of the gut and Vibrio cholerae remain poorly probed.

Gut wars

In a new study titled “Human commensal gut Proteobacteria withstand type VI secretion attacks through immunity protein-independent mechanisms,” published in the journal Nature Communications this week, scientists explore how a group of human commensal bacteria called Proteobacteria withstand the attacks of Vibrio cholerae’s T6SS killing device, using in vitro study design based on interbacterial killing assays.

“This work provides us with some new insight into bacterial community behavior within the intestinal microbiota and how defense against T6SS intoxication might help bacterial populations to defend themselves against invading pathogens,” says Melanie Blokesch, PhD, senior author on this paper and professor at the Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology, Global Health Institute, School of Life Sciences, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL).

The researchers collect commensal Proteobacteria from human volunteers. These include bacterial species such as Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, and various Klebsiella species.

Surprisingly, the new study shows, that although Vibrio cholerae’s T6SS killing device manages to kill off most commensal bacteria, some bacterial species successfully resist its scythe.

For instance, the encapsulated gut bacteria Klebsiella shield themselves against the T6SS attacks of Vibrio cholerae with their characteristic carbohydrate capsule.

More ingenious gut microbes, such as the opportunistic pathogen Escherichia cloacae neither produces its own immune proteins like Vibrio cholerae’s defense strategy against TS66, nor does it protect itself within a capsule. Instead, it has its own T6SS artillery that outranks Vibrio cholerae’s. With this it proceeds to kill Vibrio cholerae, unless of course it is slain in the attack. Clearly, its motto is offense is best defense.

Hope for the future

Blokesch emphasizes this study employs in vitro protocols and therefore additional studies are needed to get a more complete and biologically relevant picture.

Nevertheless, the authors conclude, “Our work could serve as a starting point to rationally design T6SS-shielded probiotic strains that are able to restore defective colonization barriers or enhance the barriers’ efficiency.”