Breast milk contains complex microbial communities that are thought to be important for colonizing a preterm infant’s gastrointestinal tract. Although previous research has investigated breast milk from mothers of full-term babies, little is known about the microbiota in the breast milk of mothers who have premature babies (preterm) and the factors that influence its composition. The team found that mothers of preterm babies have highly individual breast milk microbiomes, and that even short courses of antibiotics have prolonged effects on the diversity and abundance of microbes in their milk.

The study is the largest to date of breast milk microbiota in mothers of preterm infants, and it is the first to show that antibiotic class, timing, and duration of exposure have particular effects on the most common microbes in breast milk—many of which have the potential to influence growth and immunity to disease in newborns.

This work is published in the article, “Mothers of Preterm Infants Have Individualized Breast Milk Microbiota that Changes Temporally Based on Maternal Characteristics,” in Cell Host & Microbe.

“It came as quite a shock to us that even one day of antibiotics was associated with profound changes in the microbiota of breast milk,” said Deborah O’Connor, PhD, professor and chair of nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto. “I think the take-home is that while antibiotics are often an essential treatment for mothers of preterm infants, clinicians and patients should be judicious in their use.”

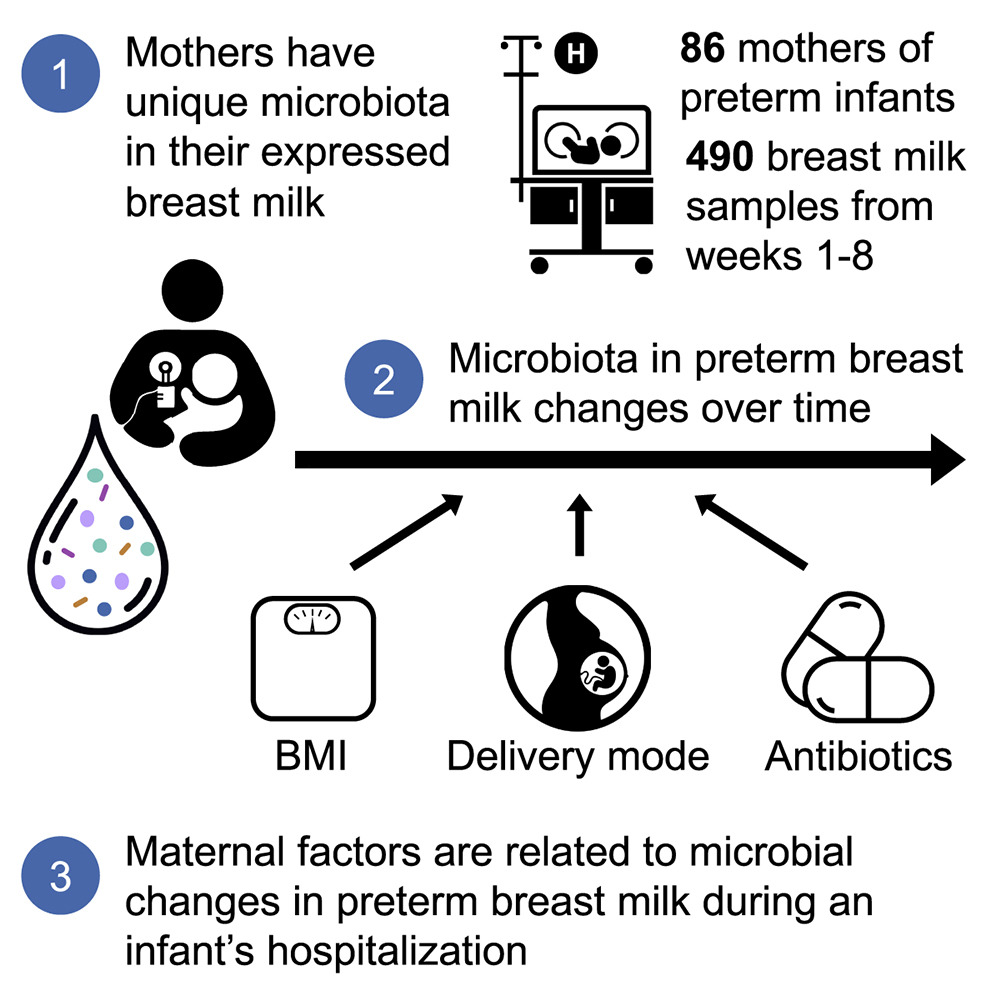

The researchers characterized the temporal dynamics of microbial communities in 490 breast milk samples from 86 mothers of preterm infants (born <1,250g) over the first eight weeks postpartum. They found highly individualized microbial communities in each mother’s milk that changed temporally with notable alterations in predicted microbial functions.

They found that the mothers’ pre-pregnancy BMI, delivery mode, and antibiotics were associated with changes in these microbial dynamics. Individual classes of antibiotics and their duration of exposure during prenatal and postpartum periods showed unique relationships with microbial taxa abundance and diversity in mother’s milk.

But the effects of antibiotics were the most pronounced, and in some cases, they lasted for weeks. Many of the antibiotic-induced changes affected key microbes known to play a role in fostering disease, or in gut health and metabolic processes that promote babies’ growth and development.

About 7% of babies born preterm develop necrotizing enterocolitis, a frequently fatal condition in which part of the bowel dies. A class of antibiotics called cephalosporins also had a big effect on the overall diversity of breast milk microbiota.

Asbury said it is too early to know what the findings mean for preterm infant health and outcomes. She and her colleagues will dive into those questions over the next year, as they compare their findings with stool samples from the preterm infants involved in the study. This should reveal whether changes in the mothers’ milk microbiomes are actually seeding the infants’ guts to promote health or increase disease risk.

Meanwhile, she added that it’s important for mothers with preterm infants to continue to take antibiotics for some cases of mastitis, blood infections, and early rupture of membranes. Roughly 60% of women in the current study took antibiotics—highlighting both the vast need for these drugs and the potential for some overuse.

Should this impact advice on breastfeeding? Sharon Unger, MD, associate staff neonatologist at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) and professor at the University of Toronto said that the benefits of breastfeeding far outweigh the risk that antibiotics can disrupt the breast milk microbiome, and that mothers should without question continue to provide their own milk when possible.

“But I think we can look to narrow the spectrum of antibiotics we use and to shorten the duration when possible,” Unger said. She added that advances in technology may allow for quicker diagnoses of infection and better antibiotic stewardship in the future.

As for the rapidly moving field of microbiome research, Unger said it holds great promise for preterm infants. “Clearly the microbiome is important for their metabolism, growth, and immunity. But emerging evidence on the gut-brain axis and its potential to further improve neurodevelopment for these babies over the long term warps my mind.”

These results highlight the temporal complexity of the preterm mother’s milk microbiota and its relationship with maternal characteristics as well as the importance of discussing antibiotic stewardship for mothers.