![Flexible neural responses were shown in an area of the brain called the ventral medial prefrontal cortex (VmPFC) during sustained stress exposure. [Yale]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Jul20_2016_Yale_InteriorBrain1008819967-1.jpg)

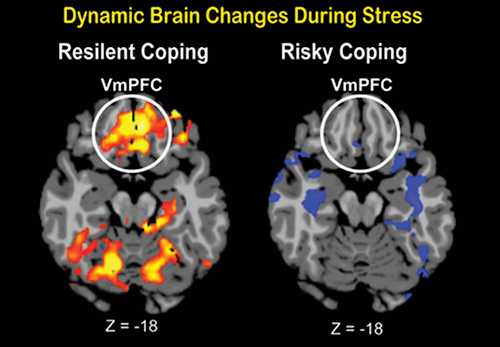

Flexible neural responses were shown in an area of the brain called the ventral medial prefrontal cortex (VmPFC) during sustained stress exposure. [Yale]

Scientists at Yale University say they have identified brain patterns in humans that appear to underlie “resilient coping,” the healthy emotional and behavioral responses to stress that help some people handle stressful situations better than others.

In a study (“Dynamic Neural Activity during Stress Signals Resilient Coping”) of human volunteers, published in PNAS, scientists led by Rajita Sinha, Ph.D., and Dongju Seo, Ph.D., used a brain scanning technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure localized changes in brain activation during stress. Study participants were given fMRI scans while exposed to highly threatening, violent, and stressful images followed by neutral, nonstressful images for six minutes each. While conducting the scans, researchers also measured nonbrain indicators of stress among study participants, such as heart rate and levels of cortisol, a stress hormone, in blood.

The brain scans revealed a sequence of three distinct patterns of response to stress, compared to nonstress exposure. The first pattern was characterized by sustained activation of brain regions known to signal, monitor, and process potential threats. The second response pattern involved increased activation, and then decreased activation, of a circuit connecting brain areas involved in stress reaction and adaptation, perhaps as a means of reducing the initial distress to a perceived threat.

“The third pattern helped predict those who would regain emotional and behavioral control to stress,” said Dr. Sinha, professor of psychiatry and director of the Yale Stress Center. This pattern involved what Dr. Sinha and colleagues described as neuroflexibility in a circuit between the brain’s medial prefrontal cortex and forebrain regions, including the ventral striatum, extended amygdala, and hippocampus, during sustained stress exposure.

Dr. Sinha and her colleagues explain that this neuroflexibility was characterized by initially decreased activation of this circuit in response to stress, followed by its increased activation with sustained stress exposure. “This seems to be the area of the brain which mobilizes to regain control over our response to stress,” said Dr. Sinha.

The authors note that previous research has consistently shown that repeated and chronic stress damages the structure, connections, and functions of the brain’s prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex is the seat of higher-order functions, such as language, social behavior, mood, and attention, and also helps regulate emotions and more primitive areas of the brain.

In the current study, the researchers reported that participants who did not show the neuroflexibility response in the prefrontal cortex during stress had higher levels of self-reported binge drinking, anger outbursts, and other maladaptive coping behaviors. They hypothesize that such individuals might be at increased risk for alcohol use disorder or emotional dysfunction problems, which are hallmarks of chronic exposure to high levels of stress.

“This important finding points to specific brain adaptations that predict resilient responses to stress,” said George F. Koob, Ph.D., director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, part of NIH and a supporter of the study. “The findings also indicate that we might be able to predict maladaptive stress responses that contribute to excessive drinking, anger, and other unhealthy reactions to stress.”