Now that the holiday glut is on the downswing and New Year’s resolutions to get fit and trim are coming into focus, investigators at the University of Copenhagen have uncovered the underlying metabolic mechanisms of how physical activity aids the reduction of annoying belly fat. The researchers found that the signaling molecule IL-6 plays a key role in this lipid breakdown process and released their finding recently in Cell Metabolism through an article titled “Exercise-Induced Changes in Visceral Adipose Tissue Mass Are Regulated by IL-6 Signaling: A Randomized Controlled Trial.”

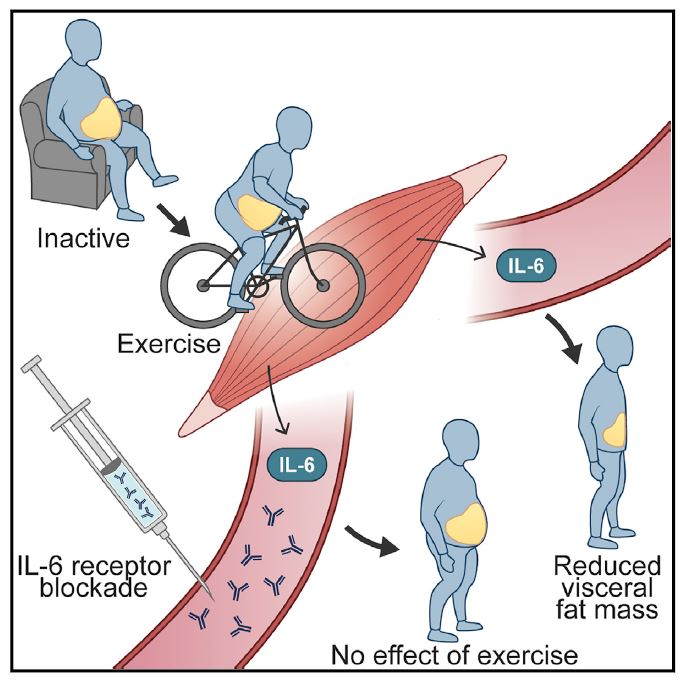

In the current study, the research team constructed a small, controlled clinical trial consisting of a 12-week bicycle exercise intervention. Not surprisingly, the physical exercise decreased visceral abdominal fat in obese adults. However, this effect was abolished in participants who were also treated with tocilizumab, a drug that blocks interleukin-6 signaling and is currently approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Moreover, tocilizumab treatment increased cholesterol levels regardless of physical activity.

“The take home for the general audience is ‘do exercise,'” notes lead study investigator Anne-Sophie Wedell-Neergaard, a graduate student at the University of Copenhagen. “We all know that exercise promotes better health, and now we also know that regular exercise training reduces abdominal fat mass and thereby potentially also the risk of developing cardio-metabolic diseases.”

Abdominal fat has been shown previously to increase the risk of not only cardio-metabolic disease, but also cancer, dementia, and overall mortality rates. Physical activity reduces visceral fat tissue, which surrounds internal organs in the abdominal cavity, yet until now, the underlying mechanisms have not been clear. Some researchers have proposed that a “fight-or-flight” hormone called epinephrine mediates this effect. Though, the research team suspected that interleukin-6 could also play an important role because it regulates energy metabolism, stimulates the breakdown of fats in healthy people, and is released from skeletal muscle during exercise.

To test their hypothesis, the researchers gathered a total of 53 participants that received intravenous infusions of either tocilizumab or saline as a placebo every four weeks, combined with no exercise or a bicycle routine consisting of several 45-minute sessions each week—for a total of 12 weeks. The researchers used magnetic resonance imaging to assess visceral fat tissue mass at the beginning and end of the study.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that interleukin-6 has a physiological role in regulating visceral fat mass in humans,” Wedell-Neergaard says.

While the investigators are excited by their findings, they note that the study was exploratory and not intended to evaluate a given treatment in a clinical setting. Moreover, to complicate matters, interleukin-6 can have seemingly opposite effects on inflammation, depending on the context. For example, chronic low-grade elevations of interleukin-6 are seen in patients with severe obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

“The signaling pathways in immune cells versus muscle cells differ substantially, resulting in pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory actions so that interleukin-6 may act differently in healthy and diseased people,” Wedell-Neergaard explains.

In future studies, the researchers will test the possibility that interleukin-6 affects whether fats or carbohydrates are used to generate energy under various conditions. They will also investigate whether more interleukin-6, potentially given as an injection, reduces visceral fat mass on its own.

“We need a more in-depth understanding of this role of interleukin-6 in order to discuss its implications,” Wedell-Neergaard states.

In the meantime, the authors have some practical holiday exercise tips. “It is important to stress that when you start exercising, you may increase body weight due to increased muscle mass,” Wedell-Neergaard concludes. “So, in addition to measuring your overall body weight, it would be useful, and maybe more important, to measure waist circumference to keep track of the loss of visceral fat mass and to stay motivated.”