![New study finds that children born after being exposed to the highest levels of organochlorine chemicals during their mother's pregnancy were roughly 80% more likely to be diagnosed with autism. [USGS]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/fs17096_foodchain1121485146-1.png)

New study finds that children born after being exposed to the highest levels of organochlorine chemicals during their mother’s pregnancy were roughly 80% more likely to be diagnosed with autism. [USGS]

The search for the underlying causes of autism has sparked heated debates and an unfortunate glut of bad science. Most notable was the thoroughly debunked Wakefield study that erroneously tied vaccinations to the rise in autism rates. Scientists have been trying actively to repair some of the lasting damage that has befallen not only the science behind vaccinations but also the research surrounding autism, which is always called into question due to previous failings.

In the past several years, researchers have published findings linking various mutant genes to cases that fall within the autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, these studies only account for a small number of ASD cases, and scientists are still unclear as to how these particular genetic mutations arise. Now, investigators at Drexel University have published evidence that several chemicals used in certain pesticides and as insulating material banned in the 1970s may still be haunting us—hypothesizing a link between higher levels of exposure to these chemicals during pregnancy and significantly increased odds of ASD in children.

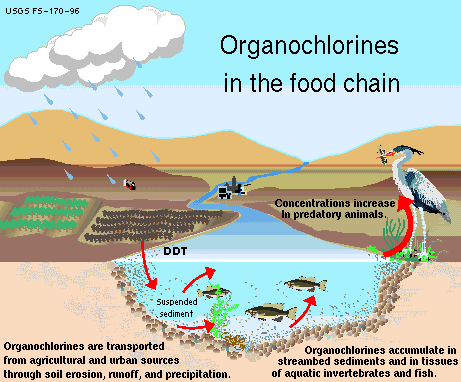

The Drexel team found that children born after being exposed to the highest levels of organochlorine chemicals during their mother's pregnancy were roughly 80% more likely to be diagnosed with autism when compared to individuals with the very lowest levels of these chemicals. Although production of organochlorine chemicals was banned in the United States in 1977, these compounds have been shown to remain in the environment and become absorbed in the fat of animals that humans eat, leading to exposure.

This led the research team to look at organochlorine chemicals during pregnancy because they can cross the placenta barrier and affect the fetus' neurodevelopment.

“There's a fair amount of research examining exposure to these chemicals during pregnancy in association with other outcomes, like birth weight—but little research on autism, specifically,” explained Kristen Lyall, Sc.D., assistant professor in Drexel University's A.J. Drexel Autism Institute. “To examine the role of environmental exposures in risk of autism, it is important that samples are collected during time frames with evidence for susceptibility for autism—termed 'critical windows' in neurodevelopment. Fetal development is one of those critical windows.”

The research team looked at a population sample of 1144 children born in southern California between 2000 and 2003. Data was accrued from mothers who had enrolled in California's Expanded Alphafetoprotein Prenatal Screening Program, which is dedicated to detecting birth defects during pregnancy. The participants' children were separated into three groups: 545 who were diagnosed with ASD, 181 with intellectual disabilities but no autism diagnosis, and 418 with a diagnosis of neither.

The findings from this study were published recently in Environmental Health Perspectives in an article entitled “Polychlorinated Biphenyl and Organochlorine Pesticide Concentrations in Maternal Mid-Pregnancy Serum Samples: Association with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability.”

Blood tests were taken from mothers in their second trimester and used to determine the level of exposure to two different classes of organochlorine chemicals: polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs, which were used as lubricants, coolants, and insulators in consumer and electrical products) and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs, which include chemicals like DDT).

“Exposure to PCBs and OCPs is ubiquitous,” Dr. Lyall noted. “Work from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which includes pregnant women, shows that people in the U.S. generally still have measurable levels of these chemicals in their bodies.”

Yet, the exposure levels seemed to be key in determining risk, with Dr. Lyall emphasizing that “adverse effects are related to levels of exposure, not just presence or absence of detectable levels. In our southern California study population, we found evidence for modestly increased risk for individuals in the highest 25th percentile of exposure to some of these chemicals.”

Interestingly, the investigators found that two compounds in particular—PCB138/158 and PCB153—stood out as being significantly linked with autism risk. Children with the highest in utero levels of these two forms of PCBs were between 79% and 82% more likely to have an autism diagnosis than those found to be exposed to the lowest levels. High levels of two other compounds, PCB170 and PCB180, were also associated with children being approximately 50% more likely to be diagnosed.

“The results suggest that prenatal exposure to these chemicals above a certain level may influence neurodevelopment in adverse ways,” Dr. Lyall concluded. “We are definitely doing more research to build on this—including work examining genetics, as well as mixtures of chemicals. This investigation draws from a rich dataset, and we need more studies like this in autism research.”