![Images across the top show compilations of PET brain scans of people who are cognitively normal. Images across the bottom show compilations of PET brain scans of patients with symptoms of mild Alzheimer's disease. The difference between scans of healthy people and scans of patients with mild Alzheimer's disease is much more apparent in the images that measure tau (right four images), suggesting tau protein buildup in the brain is a better marker of Alzheimer's disease symptoms than the long-studied amyloid beta buildup (left four images). [Matthew R. Brier]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/115285_web1341001851.jpg)

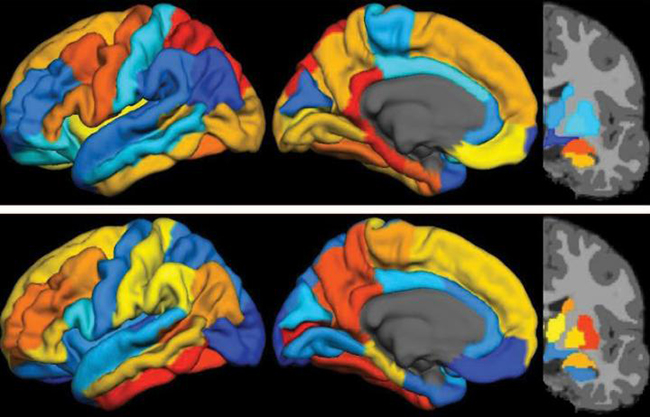

Images across the top show compilations of PET brain scans of people who are cognitively normal. Images across the bottom show compilations of PET brain scans of patients with symptoms of mild Alzheimer’s disease. The difference between scans of healthy people and scans of patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease is much more apparent in the images that measure tau (right four images), suggesting tau protein buildup in the brain is a better marker of Alzheimer’s disease symptoms than the long-studied amyloid beta buildup (left four images). [Matthew R. Brier]

Give a smoldering fire an infusion of new air or fuel and it will quickly ignite back into a rolling blaze. For decades, there has been a seething division in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research that has divided the field between two principal hypotheses—amyloid and tau proteins as the most important in AD pathogenesis. Much of the literature and early AD work has focused its attention on amyloid protein, specifically amyloid beta (Aβ); but in the past several years scientists have had a renewed interest in tau protein and its role in AD progression.

Now, investigators at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (WUSM) report on new findings that show measures of tau are better markers of the cognitive decline characteristics of Alzheimer's than measures of Aβ, as visualized in positron emission tomography (PET) scans. These new results for tau have come about due to that fact that only recently had researchers developed effective ways to image tau.

The WUSM team was able to compare brain images of individuals who were cognitively normal to patients with mild AD—uncovering that measures of tau better predict symptoms of dementia than measures of Aβ. To determine degrees of cognitive impairment, some of the participants who underwent brain imaging also were assessed with the traditional clinical dementia rating (CDR) scale, cerebrospinal fluid measures, and widely used pen and paper tests of memory and other brain functions.

“Our work and that of others has shown that elevated levels of amyloid beta are the earliest markers of developing Alzheimer's disease,” explained senior study author Beau Ances, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of neurology at WUSM. “But in the earliest stages of Alzheimer's disease, even with amyloid buildup, many patients are cognitively normal, meaning their memory and thought processes are still intact. What we suspect is that amyloid changes first and then tau, and it's the combination of both that tips the patient from being asymptomatic to showing mild cognitive impairment.”

This new study included 36 control participants who were cognitively normal and 10 patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. While the researchers urge caution in overinterpretation of the results, as well as calling for larger follow-up studies, they noted that this analysis has helped establish that the new tau imaging agent, called T807, is an important tool for understanding the timeline of Alzheimer's progression and for defining which regions of the brain are involved.

The findings from this study were published recently in Science Translational Medicine in an article entitled “Tau and Aβ Imaging, CSF Measures, and Cognition in Alzheimer’s Disease.”

“Usually, we can only diagnose patients later in the disease process, when brain function already is diminished,” Dr. Ances remarked. “We want to develop ways to make an earlier diagnosis and then design trials to test drugs against amyloid buildup and tau buildup. While we currently cannot prevent or cure Alzheimer's disease, delaying the onset of symptoms by 10–15 years would make a huge difference to our patients, to their families and caregivers, and to the global economy.”

Beyond establishing a disease progression timeline, the new tool is vital to gathering spatial information about affected brain areas. Elevated tau measured in cerebrospinal fluid has long been a marker of dementia; however, this type of data could not pinpoint which parts of the brain were gathering abnormal proteins.

“The spinal fluid measures are very important, but they don't give us a complete spatial picture,” Dr. Ances noted. “Our new study suggests you can tolerate a certain amount of tau clumped in the hippocampus, but once it starts spreading into other areas, especially the lateral temporal and parietal lobes, that seems to be the tipping point.”

The new agent is approved for use in the context of clinical research trials and likely will prove to be important in imaging the brain for other types of disorders that also involve excess tau buildup, including traumatic brain injury.