He came, He saw, but He was widely condemned as he tried to defend his controversial genome editing study, which has resulted in the birth of twins, before hundreds of scientists, ethicists, and a throng of the world media the likes of which is almost never seen at a scientific conference.

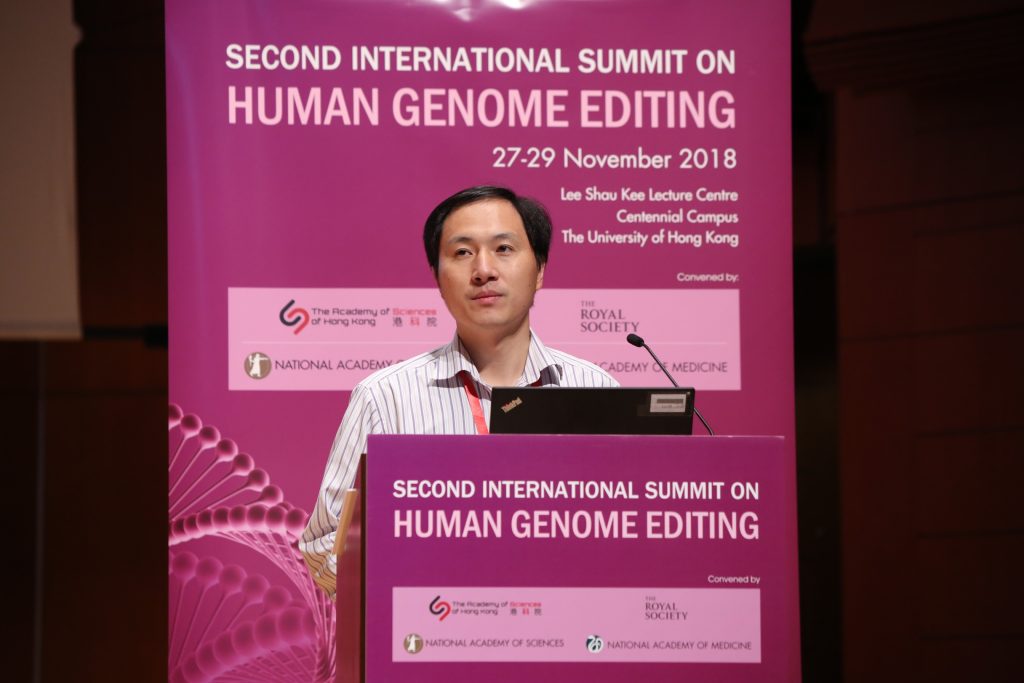

After intense anticipation whether He Jiankui, Ph.D., would indeed appear as scheduled, he finally made his entrance for a hastily rearranged session at the second international Summit on Human Genome Editing.

Dr. Jiankui strode purposefully on stage like a commuter, carrying a brown briefcase from which he pulled his notes and addressed the packed auditorium, with thousands more watching online, for 20 minutes. Session host Robin Lovell-Badge, irked by the clattering camera shutters, scolded the photographers and told them to be quiet so Dr. Jiankui could present, or the session would be canceled.

Dr. Jiankui presented the most detailed analysis to date of the rationale, screening, and regulatory procedures that led to the recent birth of twins, who had received genome editing of the CCR5 gene in the hopes of preventing HIV infection. (Their father is HIV positive.) Following his presentation, Dr. Jiankui was quizzed by Lovell-Badge and Stanford’s Matthew Porteus, along with questions from the audience and media.

The most intense criticisms centered on whether Dr. Jiankui’s choice to edit the CCR5 gene qualified as an “unmet medical need,” the regulatory and informed-consent approval process, and the timing and manner of the release of the news. Dr. Jiankui was working with a team from the Associated Press to release an exclusive story at a later date, likely around publication of a peer-reviewed article, but those plans were quashed when MIT Technology Review revealed (prior to the conference) Dr. Jiankui’s genome-editing clinical trial registration and patient recruitment plans.

Nobel Laureate David Baltimore was critical: “I don’t think it’s been a transparent process, we only found out about it after it’s happened and the children are born. I personally don’t think it was medically necessary…I think there’s been a failure of self-regulation by the scientific community because of a lack of transparency.”

David Liu, of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Broad Institute pressed Dr. Jiankui on the “unmet medical need”. “You already do sperm washing to generate uninfected embryos that could give rise to uninfected babies,” Liu said. Dr. Jiankui’s justification was to stress the public health menace of HIV affecting millions of patients rather than to focus on an individual family.

Other questions centered on the duration and expertise of the informed-consent process. Questions are also being raised by Chinese authorities. And still more questions surround the genetic surgery Dr. Jiankui’s team performed, which do not conclusively show (at least in one case) that the desired effect—a null CCR5 allele—has been created.

Dr. Jiankui was asked if he had any plans to post a draft of his manuscript on a preprint server such as bioRxiv; Dr. Jiankui said he had considered doing so earlier but had been advised against it. He indicated that he would reconsider that position.

Criticism of Dr. Jiankui’s work grew—“abhorrent” and “criminal” were just two reactions. Speaking to CNN, Jennifer Doudna said, “I don’t think there’s any way to defend using a brand new and experimental technology when there are established ways of avoiding HIV transmission… There’s just no way to defend it.”

Earlier in the summit, however, George Daley, M.D., Ph.D., dean of Harvard Medical School, struck a more conciliatory tone, counseling the audience and the wider community to learn from the problems with Dr. Jiankui’s study. “Just because the first steps [in germline editing] are missteps doesn’t mean we shouldn’t step back, restart, and think about plausible and responsible pathway for clinical translation,” Dr. Daley said.

In the statement that resulted from the inaugural Human Gene Editing summit in 2015, the organizers firmly concluded: “It would be irresponsible to proceed with any clinical use of germline editing unless and until…” safety concerns could be set aside, a societal consensus about the appropriateness of the application could be reached, and appropriate regulatory oversight was in place. “At present, these criteria have not been met for any proposed clinical use,” Dr. Daley said.

Dr. Daley noted that there have been dozens of reports published over the past three years on human genome and germline editing. (Dr. Daley highlighted a recent review by Carolyn Brokowski in The CRISPR Journal.) But Dr. Daley noted an interesting evolution in the tone of some of the major ethics reports, with the 2017 U.S. National Academies of Sciences and Medicine report recommending “a need for caution” in any move towards germline editing, “but that caution does not mean prohibition.” The following year, a major report by the U.K.’s Nuffield Council said, “We can, indeed, envisage circumstances in which heritable genome-editing interventions should be permitted.”

It is time, Dr. Daley argued, “to move forward from prospects of ethical feasibility to defining the pathway and regulatory standards that a group would be held to in order to bring this technology forward. If we’re ever going to practice this with a deep sense of social justice, there needs to be additional definition between permissible and impermissible.”

“The fact that the first example came forward as a misstep should in no way lead us to stick our heads in the sand and not consider the very positive aspects that could come forth from a more responsible pathway to clinical translation.”

Dr. Daley closed saying: “The fundamental principle of self-regulation is something the scientific community has adhered to and is something I would defend.”