January 1, 2013 (Vol. 33, No. 1)

Opportunities Abound in Rare Disease Space as Market Is Projected to Continue Growing

Orphan diseases affect some 25 million Americans and, 30 years after passage of the Orphan Drug Act, are becoming a lucrative market for biotech companies strapped for cash and slowed by regulatory hurdles. As therapeutics move toward personalized medicine, the appeal of orphan drugs continues to grow—particularly as diseases become increasingly segmented and therapeutics’ cross-over potential is discovered.

“Amidst the continuing patent expiries, orphan drugs provide pharmaceutical companies an opportunity simultaneously to increase their revenues and benefit society,” according to Geetika Munjal, analyst for GBI Research. “Fewer competitors and high unmet need leads to high prices for these drugs, offsetting the smaller patient population and making these products economically viable. Smaller clinical trial size, shorter trial time, and commercial benefits such as fast track approval, tax credits, and fee waivers attract multinational corporations to the rare disease segment,” Munjal explains.

The field is ripe. Orphan status is granted to drugs for which the costs of developing and marketing a therapeutic are unlikely to be recovered, and in the U.S., to diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people, and in the EU to diseases that affect 5 in 10,000. The EMA recognizes 8,000 rare diseases, the FDA 6,000. Since the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 was passed, the FDA has approved the development and marketing of some 350 drugs and biologics for approximately 200 orphan diseases.

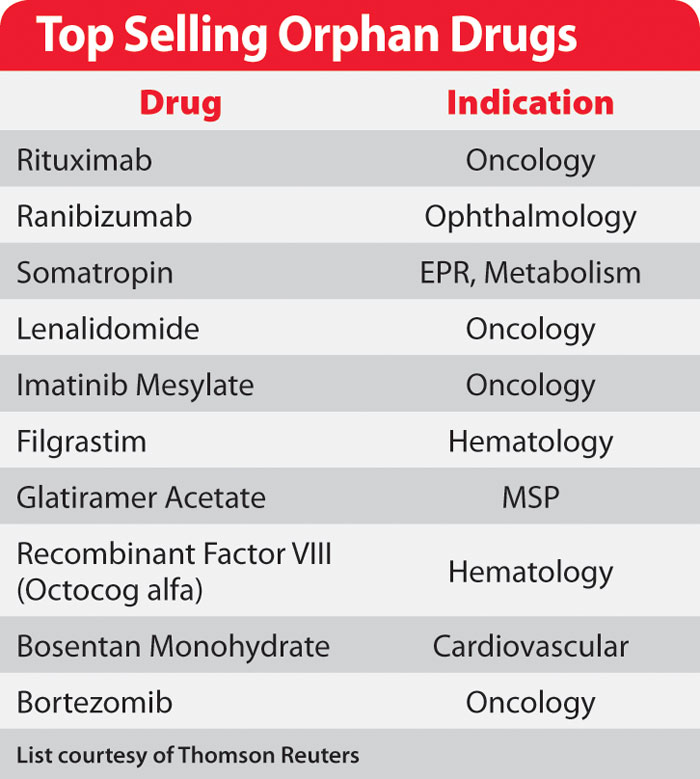

Globally, Thomson Reuters reports orphan disease therapeutics grew at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of nearly 26% between 2000 and 2010, versus a CAGR of 20% for nonorphan drugs. They account for 22% of current drug sales, with a current global value of $50 billion. Oncology is the most common therapeutic area, accounting for 40% of the ten leading drugs. That segment has a lifetime earnings potential of $70 billion per drug. The remaining indications have a lifetime earnings potential of $41 billion per drug.

The value proposition for orphan drugs has shifted, so that orphan drugs that are actively developed and filed have a 93% probability of success, versus 88% for nonorphan drugs, according to Thomson Reuters’ Kiran Meekings, Ph.D. She estimates present values at $637 million per year for orphan drugs and $638 million per year for nonorphan drugs, using 2010 dollars.

As Dr. Meekings tells GEN, “Companies that have business models based upon the development of rare diseases will continue to be successful.”

Shire is among them. It formed a strategic collaboration with Sangamo BioSciences in February 2012 to develop therapeutics for hemophilia, Huntington’s disease, and other monogenic diseases based upon Sangamo’s zinc finger DNA-binding protein technology. Shire also is developing therapeutics for mucopolysaccharidosis type II (Hunter syndrome), metachromatic leukodystrophy, and Sanfilippo A and B syndromes.

BioMarin Pharmaceutical plans to submit marketing applications for GALNS, its enzyme-replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis Type IVA (MPS IVA)—Morquio A Syndrome—in early 2013. The company also has a Phase II trial under way for phenylketonuria (PKU) and Phase I trials in progress for Pompe disease, the PARP inhibitor for genetically defined cancer, and the analog of CNP for achondroplasia.

“Genzyme’s success in developing profitable treatments for rare diseases—such as Cerezyme® for Gaucher disease, Fabrazyme® for Fabry disease, and Myozyme® for infantile Pompe disease—has demonstrated a reproducible business model for multinational corporations,” Munjal says. This is despite a small target population and its acquisition by Sanofi in 2011.

Currently, Genzyme is developing therapeutics for lysosomal storage disorders, including an additional therapy for Gaucher disease. Endocrinology and cardiovascular disease therapeutics also are in development. Five orphan therapies are on the market and others are in development to improve potency or delivery methods, and expand the number of diseases treated.

“There are also a growing number of mainstream pharmaceutical companies that are getting into the rare disease space,” Dr. Meekings says. “Companies such as Roche, which has demonstrated success in concomitantly developing products and diagnostics, will be ones to watch within the ‘sub-disease’ space.”

“Understanding mechanisms of action for rare diseases also enhances work in related diseases and helps establish a revenue stream while other therapeutics are developed,” notes Diane Dorman, vp, public policy, National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD). “Some companies are dedicated to repositioning drugs for orphan diseases. That strategy has the potential to be highly successful.” Additionally, some large pharmas are establishing rare disease units and re-evaluating molecules for orphan disease applications.

For example, Pfizer’s orphan and genetic disease unit focuses its research on protein challenges that underlie many rare, genetic diseases. It pays particular attention to hematology and neuromuscular diseases. Pfizer and Protalix received approval by the FDA in May for taliglucerase alfa (Elelyso™) as a long-term enzyme-replacement therapy for type 1 Gaucher disease, but were denied EMA approval in favor of Shire’s earlier EMA-approved therapeutic. Other global filings are under way.

GlaxoSmithKline formed its rare disease unit in 2010 to identify and develop treatments for the rare diseases it deemed most likely to respond. Research focuses on 200 rare diseases, categorized into central nervous system and muscle disorders, immunoinflammation, rare malignancies and hematology, and metabolism and inherited disorders.

At least three compounds are in Phase III trials for rare diseases. An antisense oligonucleotide targets Duchenne muscular dystrophy in collaboration with Prosensa, an ex vivo stem cell gene therapy targets adenosine deaminase severe combined immune deficiency and migalastat hydrochloride, and a pharmacological chaperone for Fabry disease is in development with Amicus Therapeutics. GSK also has partnered with JCR Pharmaceuticals, Isis Pharmaceuticals, Fondazione Telethon, and Fondazione San Raffaele for gene therapies.

Emergent BioSolutions, the only U.S. manufacturer of anthrax vaccine, is in clinical trials with zanolimumab as a treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, and with TRU-016, a humanized anti-CD37 therapeutic that treats chronic lymphocytic leukemia as well as the more mainstream condition of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Top Selling Orphan Drugs

Sickle Cell

“Lastly,” Dr. Meekings says, “in terms of innovation, there are a large number of players trying new things.” Sickle cell disease is a good example. With only one FDA-approved drug available, several small, innovative companies are developing compounds to address the disease and the accompanying vaso-occlusion and underlying ischemia and infarction.

Adventrx Pharmaceuticals, for example, is finalizing a Phase III trial design for ANX-188, a compound that improves microvascular blood flow by reducing viscosity. A 250-patient trial by previous sponsor GSK narrowly missed its endpoint. Adventrx is expanding the study to 400 patients and is evaluating ANX-188 for additional indications.

AesRx has a Phase I/IIa trial under way for Aes-103 in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health. This small molecule increases the affinity of sickle hemoglobin for oxygen, thus reducing the number of cells that can sickle.

Erytech Pharma is advancing Enhoxy, a human erythrocyte encapsulating inositol hexaphosphate, which enables red blood cells to release more oxygen.

HemaQuest Pharmaceuticals’ HQK01001 compound simulates fetal hemoglobin expression and red blood cell production. It is in Phase IIb trials, and received a $13 million extension of its Series B financing in March 2012.

Sub-Diseases

“There are a growing number of orphan indications that are actually sub-populations of larger nonrare diseases, such as BRAF mutated melanoma and ALK-translocated NSCLC,” Dr. Meekings says. Oncology is a good example.

The orphan oncology drug market is expected to grow at a CAGR of 3.3%, reaching $6.4 billion by 2018 in the leading markets, according to the GBI Research report, “Orphan Diseases Therapeutics in Oncology to 2018”. Growth rates vary by category. Ovarian cancer and multiple myeloma markets are expected to grow modestly because of major patent expirations. In contrast, acute myeloid leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma markets are likely to experience much higher growth, according to GBI analysts.

CNS Diseases

Huntington’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis are among the leading orphan CNS diseases, according to GBI Research in its report, “Orphan Diseases Therapeutics in CNS to 2017”.

That report indicates a global 8% CAGR between 2002 and 2010, with an increase from $359.6 million in 2002 to $665.5 million in 2010. By 2017, GBI predicts that growth will increase to a 17.6% CAGR, with annual sales of $2.1 billion.

By GBI accounts, the greatest growth in the orphan CNS market is most likely for Huntington’s disease, which is projected to have a $786.5 million market by 2017. That’s a 29.8% growth rate from 2010, up from 17.8% between 2002 and 2010. For myasthenia gravis, the growth rate is expected to be 6.3% between 2010 and 2017, up from 3.9% between 2002 and 2010. ALS therapeutics, however, will slow. Despite being one of the leading orphan markets in 2010, GBI predicts a CAGR of 3.7%, down from 5.1% between 2002 and 2010.

Major players in the orphan CNS market include Biogen Idec, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Neuraltus Pharmaceuticals, Cytokinetics, The Avicena Group, NeuroSearch, Trophos, Amarin, Siena Biotech, and Sanofi.