When a patient arrives at the emergency room with severe chest pain, doctors may quickly establish a heart attack diagnosis by using a variety of tests. Blood tests and electroencephalograms, for example, both provide information that is useful not only for making a definitive diagnosis, but also for assessing the extent of damage to the heart and informing a course of treatment. Tests that could accomplish analogous tasks in other emergencies, however, are sometimes lacking. For example, no tests are available that could confirm concussion.

Because medicine currently lacks a comprehensive diagnostic toolkit for concussion, patients admitted with head injuries might walk away from the emergency room with a prescription for little more than bed rest. Even when patients are correctly diagnosed, there are few effective treatment options.

Speedy diagnosis is a major concern among military personnel and athletes, whose eagerness to get back into the fray as soon as possible makes it less likely that they’ll report a head injury in the first place—and more likely that they’ll sustain another one soon after.

In the field, coaches and corpsmen have a few quick diagnostic measures at their disposal, but these measures rely heavily on verbal self-report, and athletes or soldiers might not be forthcoming about how they really feel.

Failing to report or recognize concussion can lead to serious neurological damage down the road, according to Donald W. Marion, MD, a neurosurgery consultant with the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center in Silver Spring, MD. Maron recently moderated a roundtable discussion on ongoing efforts to identify blood-based biomarkers for concussion. (The full discussion is available in a supplement to the Journal of Neurotrauma, which is published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.)

Blood tests for brain damage

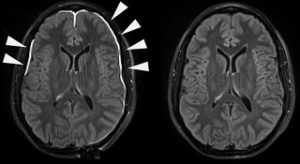

“What we’ve been looking for, for probably several decades now, is an objective marker that wouldn’t depend on the patient volunteering symptoms,” Marion tells GEN. While protein signatures of other kinds of tissue damage have existed for decades, similar markers of brain injury have only recently emerged. Jessica M. Gill, PhD, acting scientific director at the National Institute of Nursing Research at the NIH, noted that glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and several other proteins have been found whose presence in the bloodstream can reliably indicate brain injury.

“These blood biomarkers go a lot further in our assessment and characterization of brain injury,” said roundtable participant Michael A. McCrea, PhD, a professor of neurosurgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Although these biomarkers represent progress, it’s still unclear whether levels of these proteins correlate to a patient’s ability to function. Jeffrey J. Bazarian, PhD, a professor of emergency medicine and neurology at the University of Rochester, pointed out that patients presenting with symptoms of concussion may also have underlying dementia or other injuries that affect function and could therefore muddy the diagnostic waters. Still, if they’re specific and sensitive enough, blood-based biomarkers could also help doctors quickly rule out a concussion if other factors are at play.

When diagnosing concussion, timing is everything

There are still a few obstacles to the wider adoption of blood-based biomarkers as a standard diagnostic practice after a head injury. For one, the FDA has approved these biomarkers only as a way to validate a suspected concussion based on imaging results, not as standalone diagnostics. Rapid diagnosis is also critical for patient care.

Ava Puccio, PhD, an assistant professor of neurosurgery at the University of Pittsburgh, stressed the need for a quick point-of-care tool like those used for blood glucose tests, where a drop of blood from a finger prick can turn around readings in a few minutes, rather than the days usually required for a typical blood draw. Efforts are already well underway to develop detection assays for existing technology.

Portable diagnostic tools could have the greatest impact among those who are the least likely to visit the emergency room after a head injury. “The place where biomarkers have really gotten a lot of attention is mostly in the athletics field,” explains Michael S. Wyand, PhD, CEO of Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals, in an interview with GEN. “The big issue for athletes is: When can they return to play?”

Since most patients who show up with a head injury in the emergency room aren’t eager to know how long they have to wait until their next major accident, clinicians have more time to review options for treatment. Overwhelmingly, the main course of treatment is rest—but as the team at Oxeia, maintains, “rest is not enough.”

Beyond bedrest

This motto is the driving force behind OXE-103, a synthetic version of the hunger hormone ghrelin, which Oxeia is developing as the first therapeutic intervention tailored to concussion. While initially used to treat anorexia due to its efficacy as an appetite stimulant, it was soon discovered to have a variety of neuroprotective functions, too. Head injuries throw off the brain’s energy balance, and ghrelin seems to work not only to restore this balance, but also to strengthen connections between neurons, which can be disrupted by the trauma of impact.

Oxeia has already begun Phase II clinical trials on OXE-103. As the first drug of its kind, the information Oxeia gleans from these trials will be invaluable not only for future treatments, but potentially for diagnostics as well. In addition to tracking the cognitive and physical symptoms of patients receiving the drug, the company also plans to measure levels of biomarkers in the blood, and to develop meaningful correlations between these levels and patient functions at various timepoints following a head injury.

Historically, management of concussion has been limited by both a lack of clinical tools and understanding, with patients often dismissing an injury only to seek care to manage the long-term effects later on. Now, as more of the serious neurological side effects of concussion have come to light, basic research is quickly catching up to the need for targeted diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Further along the clinical pipeline, Oxeia foresees marketing OXE-103 in a portable form, making it even easier for those at higher risk of repeated injury to receive care without delay. As Manley stated in the roundtable discussion, “I think that on the one hand, we have got some very practical things that we are seeing acutely that we can do, and a lot of promise for other things that we may find in the future.”