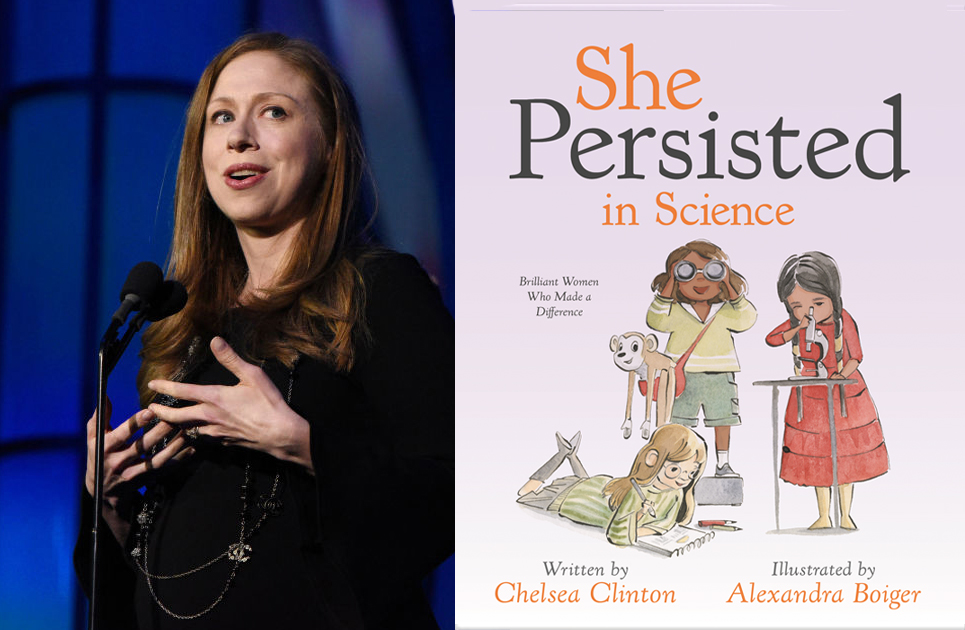

The Rosalind Franklin Society (RFS) and Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News (GEN) had the pleasure of co-hosting an interview with Chelsea Clinton—a champion of women who persist and pursue their passions. Her mission currently takes the form of a new children’s book series entitled She Persisted. The most recent in the series, She Persisted in Science, features 13 women scientists.

Here, Julianna LeMieux, senior science writer at GEN, talks to Clinton about her motivation to write the book, how she chose which scientists to include, and the scientists that have influenced her own life along the way.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

LeMieux: Before we talk about She Persisted in Science, can you tell us how the original She Persisted book came about?

Senator Warren thought that it was always the right time to hear from Mrs. King, especially as it relates to such an important position as the attorney general, which at the time Jeff Sessions had been nominated for.

They told her it was not fitting with decorum. They asked her to sit down. But she would not be silent. Finally, they were forced into censoring her.

Afterward, when being interviewed, Mitch McConnell cast himself as the victim of this moment when Senator Warren wouldn’t stop. Nevertheless, she persisted. And I don’t think that the Senate majority leader had any inkling of how that phrase would be so galvanizing to so many women (and thankfully also to some men.)

As I was watching all of this unfold in real time, I kept thinking about how often we’ve needed women, including Senator Warren and Mrs. King, and many others, to persist throughout American history to help advance and protect progress.

The second phenomenon was that I was keenly aware, as a mother, of how many children’s books were written from the perspective of boys—or in which the main characters were gendered male. Even the animals, which always seemed strange to me. Why are so many of the toads, pigs, frogs, cows, and ducks often, and inevitably, given male voices and conventionally boy characteristics, even though they’re farm animals?

I found that really challenging as the mother of a daughter. I also found it challenging as the mother of a son.

I purposely went looking for books written by women, or written with girl main characters. Thankfully there were some wonderful books, but it just felt like there needed to be so many more.

So, these two phenomena collided in my head, and in my heart, and I thought that I should do something about it. And my wonderful editor, with whom I had already worked on other projects, also thought that we needed more women’s stories for even our youngest readers.

So, we quickly decided to work on the first She Persisted together. And I’m so thankful that Alexandra Boiger, who is an extraordinary illustrator, agreed to work with us on the project.

LeMieux: Well, we are glad that you did. And I’m glad that you mentioned Alexandra Boiger as well because the illustrations are absolutely tremendous.

Clinton: She is brilliant. I couldn’t imagine these books without her partnership.

LeMieux: Before we dive into the book on women in science, I want to share a quick story to let you know how much of an impact the books are making. I read these books with my youngest child, who is six years old. She came home from school the other day and she said that she didn’t want to finish her cheese sandwich at school before having her cookie. When I said, “You need to eat your growing food.” She responded, “Don’t worry, Mom, I persisted.”

Clinton: Oh my gosh, I love that so much.

LeMieux: From cheese sandwiches to changing the world!

Clinton: Well, if you’re healthier, you can do even more world changing!

LeMieux: There were so many directions that you could have gone in from the original She Persisted. I’m curious, why did you choose women in science to focus on?

Clinton: I loved science as a kid. I was completely fascinated by the natural world. I always loved science classes in high school and college. And so many of the people that I found most compelling were people who had worked in the sciences.

My daughter wants to be a marine biologist when she grows up. She has loved sharks for her whole life. When she was two years old, if you asked her what her favorite animal was, she would say sharks. She’s now seven and she still says sharks. In fact, I printed out some shark workbook pages for her to do over the weekend and she said, “Mom, I already know all this.”

The focus on women in science was for reasons relating to my own childhood, to what I saw in my own kids, and to the countless children that I had interviewed and interacted with for my books written for slightly older audiences. So many kids love science, even if they may not know that what they love relates to science. So, I just thought that this is a book I want to write.

LeMieux: There are thousands of women that could be included in a book celebrating women of science. I can only imagine the challenge in narrowing it down to 13. How hard was it and what was that process like?

Clinton: It was really hard. It was important to me to include a diversity of disciplines, even though we couldn’t include every discipline.

There were some people that I really wanted to include that I got a little pushback on. For example, I really wanted to include Zaha Hadid, who is an architect, because architecture is also a science. I want kids to understand that science is all around us and that science can help us understand more than just nature, but also our built environment.

It was also important to me to include Gladys West because my children are fascinated by her. I think that it’s because they can’t believe there was ever a time that we got lost. It is a very strange concept to them that when I was their age and on road trips with Grandma and Pop Pop, we would have maps and sometimes would even have to stop and ask for directions.

So, there were some women that I really wanted to include. I also asked a wide group of people, some of whom I knew, or my editor knew, for suggestions of different scientists that they would want to see in the book.

LeMieux: I really appreciated, as somebody who worked in a lab for years, how the different women offered a wide perspective of what science is. That scientists are not only people working at the lab bench. You have women from so many different walks of science. And I think, especially for kids, that is such an important point that the women represent.

Clinton: Thank you for saying that. I want kids to find inspiration in the different stories. I wanted there to be real representation of what science can be because I think that it is important for kids to understand why science matters. And, that what they’re learning in second grade or fourth grade, or even in kindergarten or high school, can be enabling in so many different ways.

LeMieux: There are also chapter books in this series. How did you decide to move into the chapter books and which stories would turn into a chapter book?

Clinton: While on the book tours for She Persisted, I got so many questions around where people could go to learn more about these women. And sometimes there were really good places to point kids toward. But sometimes there hadn’t been much written about these women. So, we turned the first She Persisted book into a series of chapter books.

LeMieux: So, now you’ve done picture books and chapter books. Are there any other initiatives up your sleeve? Are there any more books coming out?

Clinton: More chapter books! And, in the back of each chapter book, there is a list of suggested ways that young readers can persist if inspired by these women’s remarkable lives. Each list is tailored to each woman’s story because they persisted, created, achieved, and had impacts in such a myriad of critically important ways.

We’re going to keep doing what we’re doing. But we are also trying to think about other ways to collate those lists. Is there a way to be even more robust in thinking about curriculum? We are trying to figure out what more we can do with the continued interest in these kinds of stories.

So, we will keep bringing more stories into the world through She Persisted. And we’re also trying to think about what more we can do to help support young change makers.

LeMieux: That is very exciting, and so important—especially in thinking about curriculum. My oldest child is in high school. And when he learned about the discovery of the structure of DNA, he was only taught about Watson and Crick. And that was this year, Chelsea. That illustrates that this work needs to keep going all of the way from picture books to high school.

Clinton: I didn’t learn about Rosalind Franklin until I was in college. But I had thought, clearly erroneously, that surely something had changed in the last 25 years. That’s just so disheartening. And yet as I sit here, I realize not terribly surprising that there hasn’t been a change.

I know that the Nobel committee does not give awards posthumously, but I think we have to continue to apply pressure to the gatekeepers of achievement—whether academic journals or organizations that grant prestigious awards—to be more honest about updating their history, the stories of what they recognized as achievement, and who they have recognized. Because, while certainly the structure of DNA may be one of the most egregious efforts to ensure a woman is not given a fair due, it is far from the only.

LeMieux: I’m curious to learn a little bit more about your personal interest in science and if there were any scientists along the way that influenced you in your educational direction or career path?

Clinton: My freshman advisor at Stanford was a wonderful scientist named Anne Frenald, PhD, who studied language and brain development in babies and early toddlers. It was through my conversations with her, when I was trying to figure out what I was going to do with my life, that I came to realize that I was interested in public health. But I didn’t quite know how to pursue that; there wasn’t a public health major or concentration at Stanford at the time.

She helped me understand that, even if I was planning to pursue a graduate degree in public health, it was still important to have a grounding in the life sciences so that I would have comfort and fluency with those areas of work and literature. I’m so thankful that I took statistics in college, and then later took further advanced statistics in graduate school, which was hugely important to my trajectory.

I am deeply, keenly, aware of how serendipitous it was that Dr. Frenald was my freshman advisor because she helped me understand what building blocks would be helpful, even if the specific degree wasn’t offered at that time.

LeMieux: And what was your goal in doing your graduate studies at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health?

Clinton: My interest in public health started with Magic Johnson when, in November of 1991, he declared that he was HIV positive. It should not have required courage, but at the time this was a hugely courageous decision. I became interested first in HIV and AIDS, then in stigma, and then in the policies and structures that were helping protect some people and making other people more vulnerable to HIV infection. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria was created toward the end of my time in college and I was fascinated as to why the world felt the need to create a new instrument. And what did that say about the failures of the preexisting global health architecture?

I went on to get a master’s degree in international relations with a global public health focus. And I wrote my master’s thesis on the Global Fund and its genesis. Then I got my master’s in public health and a doctorate focused on looking at the first 10 years of the global fund and whether or not it had lived up to its expectations.

LeMieux: What are your top priorities for the future?

Clinton: I hope that I have the chance to keep doing more of what I’m doing. I’m so thankful that I get to manifest the most important callings to me, in a professional sense, as an author, an academic, an advocate, and a mentor, to do anything and everything I can to further advance good public health for as many people in as many places as possible.

To me, that also means doing anything and everything I can to support women and kids’ health. And I’m so proud of all the work that we do around the world with the Clinton Health Access Initiative to do just that. And also here in the United States with a focus on early childhood development and early brain development for kids.

I hope I get to keep writing more She Persisted books and having conversations like this. And that I continue to have conversations anchored around public health and supporting women and girls through my podcast and my teaching. And that I’m able to keep investing in and supporting and championing, not only women, but especially women who are tackling challenges that relate to public health.

I hope that I just keep being able to do all that I’m doing now, because I feel so grateful for the opportunities I have now to try to help in whatever small ways I can to change the world.

LeMieux: Well, from one woman in science to another woman in science, thank you so much for joining us today and discussing all of the work that you’re doing. The phrase “you have to see it to be it” exists for a reason. When I was growing up, we didn’t know these stories of women in science that you have put into so many children’s hands. As a huge fan of the books, and a fan of supporting women in science—thank you.

Clinton: Thank you, Julianna. I see that impact, just as you were saying, in my house too. My five-year-old loves math and music beyond anything. If you were to ask him who his heroes are, he would say Catherine Johnson and Beethoven. And I think it is pretty great that my five-year-old boy doesn’t think anything about the fact that, of two heroes that he looks up to, one of whom is a woman. That is very unexceptional to him. Which, as his mother, is exceptional for me to witness. I just want to keep trying to bring that reality into being for as many kids as possible.