The Alzheimer’s disease (AD) community is buzzing over a major news story recently published in Science, which raised concerns about multiple images published in a groundbreaking paper sixteen years ago that has driven support–and copious funding–for the so-called amyloid hypothesis.

Dennis Selkoe, MD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who is a leading proponent of the amyloid hypothesis, has independently examined images from a 2006 Nature report by lead author Sylvain Lesné, PhD, currently an associate professor in the department of neuroscience at the University of Minnesota (UMN). He agrees with conclusions in the Science story that at least a dozen images in that report, as well as in other Lesné papers, show obvious signs of manipulation.

In an exclusive interview with GEN, Selkoe said, “This is a sad example of human fragility and malfeasance, but the original finding about Aß*56 in AD was felt by many of us (including me) as unlikely to be meaningful or correct when first published in 2006.”

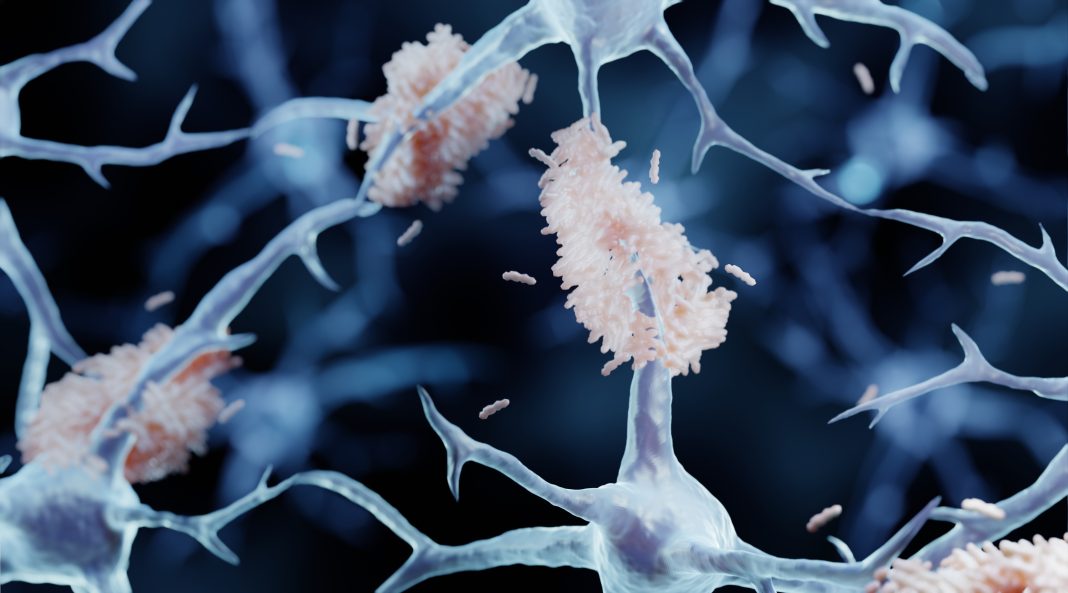

Devastating cognitive decline in AD is accompanied by the deposition of sticky beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tau tangles in the brain. With an estimated 5.8 million Americans currently living with AD—potentially reaching 14 million people by 2060—the need for effective treatments is urgent. The “amyloid and toxic oligomer hypothesis,” which proposes AD is caused by amyloid plaques and soluble amyloid oligomers, has led to the investment of billions of dollars in the development of drugs that target amyloid in its various forms.

Since publication, 2,300 studies have cited the UMN report. NIH’s annual funding for amyloid projects has exploded to $1.6 billion in the current fiscal year, supporting the considerable influence the UMN paper had in popularizing the amyloid hypothesis.

Doctored images?

In a news feature titled ‘Blots on a Field?’ published in the July 22, 2022 issue of Science, investigative science journalist Charles Piller reported on potentially doctored western blot images in scores of Alzheimer’s research articles, including images from the Lesné et al. 2006 Nature paper. These images of concern were initially unearthed by Matthew Schrag, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of neurology and director of the cerebral amyloid angiopathy clinic at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

As Piller writes, Schrag’s data interrogations on Simufilam, a drug being developed for the treatment of AD by Cassava Sciences, which claims the drug inhibits amyloid beta deposition and improves cognition, led him to analyze images in the Nature paper as well as other papers co-authored by him. Schrag, who raised questions about more than twenty of those papers, has presented his findings to the NIH, FDA, and the journals that originally published these reports, including Nature, Brain, Science Signaling, and The Journal of Neuroscience.

Schrag’s report on the questionable images in these studies is based on scrutinizing the published images and not the original “raw data.” Therefore, he is unable to definitively prove fraud or misconduct. However, Science recruited two independent image analysts and several Alzheimer’s researchers to investigate the images that Schrag found suspicious. They concurred that hundreds of images flagged by Schrag could have been tampered with, including more than 70 images in Lesné’s papers.

(In the Science article, Piller wrote that “Lesné did not respond to requests for comment. A UMN spokesperson says the university is reviewing complaints about his work.” GEN contacted the UMN public relations department for comment and received the following email. “The University will follow its processes to review the questions any claims have raised. At this time, we have no further information to provide.”)

Donna Wilcock, PhD, a professor of physiology, assistant dean of biomedicine, and associate director at the Sanders-Brown Center on Aging at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine, was part of Science’s team of Alzheimer’s experts who examined Schrag’s report. She found some of the alleged image tampering “shockingly blatant,” as per Piller’s investigative report.

In an exclusive interview with GEN, Wilcock downplayed the impact of these suspicions on the AD community. “I believe the impact on the Alzheimer’s research field is less significant–it was quite well understood among [researchers in] the field that the work was not particularly reproducible. I feel the field moved on from this concept some time ago.”

“Unfortunately, the impact on patients and the lay community is greater. Science without integrity and rigor is not science. It is opinion. Unfortunately, the findings of misconduct around Lesné’s work that goes back to his training years significantly erodes public trust in science. This is far more difficult to recover from.”

Manipulated images are an ongoing concern

Carol Reiss, PhD, professor emerita at New York University’s biology department and editor-in-chief of DNA and Cell Biology (published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., the company that publishes GEN), says manipulated images in submitted manuscripts are an ongoing concern. “It is possible to duplicate, rotate, erase, and ‘write’ images fraudulently. It is possible to select images that are consistent with a hypothesis but do not reflect the data accrued. Some of this manipulation is readily visible to the trained or skeptical eye.”

Reiss says journal editors routinely use third-party software to analyze images as well as to check for plagiarism. “For Western blots, at DNA and Cell Biology, we require scans of the whole uncropped membranes as a supplement so that the editors and reviewers can examine these images themselves. We require raw molecular data or a link to public databases where these data have been deposited.”

According to the Science story, Reiss says, there is an argument that the amyloid hypothesis dominated the conversation, research, funding, and therapeutic development following publication of the Lesné papers. “As is often the case (unfortunately), other work was not given the attention or was dismissed because it may have found other observations. Clearly Lesné and colleagues did not silence others, but the community responded in that way.”

But Selkoe does not believe Lesné’s Nature paper was seminal in the rise of the amyloid hypothesis of AD. Lesné’s pivots on a technique that Selkoe said “makes no biochemical sense.” The method, developed in Ashe’s lab by Lesné, claims to be capable of separately analyzing oligomers present inside and outside cells in solutions prepared from frozen or processed brain tissue.

Oligomers like Aβ*56 are unstable and spontaneously change into other types of oligomers, Wilcock explains in the Science story. Several labs, including Wilcock’s, have failed to detect Aβ*56. However, these negative findings have not been published. This could be due to scientists’ reservations in contradicting a well-known investigator or the general apathy of journals to publish negative data.

“This unfortunate incident does not alter the overwhelming genetic, neuropathological, animal modeling, and even human clinical trial evidence that lowering amyloid of all forms, including Aß oligomers, can modify the disease, lessen the tau tangles and lead to less clinical progression,” Selkoe said.

Setbacks, dead ends, and unreplicated data

Schrag knows first-hand that research is fraught with setbacks, dead ends, and data that cannot be replicated. His own research failed to prove a connection between AD and iron metabolism in humans after promising results in animal studies. The introduction of false ideas in scientific knowledge can warp understanding, he told Piller. This warped understanding is evident in the continued predominance of amyloid-targeted therapies in clinical trials, compared to alternative strategies that target inflammation.

At present, the only FDA-approved available drug for AD is Biogen’s controversial Aduhelm, an amyloid beta–directed monoclonal antibody. Scientists and physicians, including Schrag, have publicly criticized FDA’s approval of this drug that claims to slow down cognitive decline.

“Many therapies based on disrupting aggregates of amyloid-beta have been developed and are in the pipeline, e.g., monoclonal antibodies to ‘pull’ monomers out of the brain to prevent them from aggregating, enzyme inhibitors to block the cleavage of the amyloid subunits from the parental protein, etc.” says Reiss. “Results from almost every clinical trial to treat AD that I am aware of have been less than impressive.”

Phase III clinical trials for three amyloid-targeting drugs are currently underway: lecanemab, an anti-oligomer monoclonal from Biogen; gantenerumab, a human antibody against amyloid-beta fibrils and Aβ42 oligomers from Roche; and donanemab, a humanized mouse monoclonal antibody against Aβ(p3-42) from Eli Lilly.

“What matters are the results of [these] clinical trials that should be revealed in the next few months and are poised to be considered for approval by the FDA,” says Selkoe.

If any of these amyloid targeting drugs gain approval, neuroscientists might yet be convinced of the viability of the broader amyloid hypothesis beyond the questionable existence of Aβ*56. As Schrag points out, cheating might get someone a publication or a grant, but not a cure.

Perhaps, more important from the broader perspective of declining public trust in scientists, academic journals, and regulatory agencies, which was especially made clear during much of the COVID epidemic, is the obvious lack of transparency and accountability in the practice of science, its communication, and governance.