The verdict, after a closed-door trial in the Nanshan District People’s Court of Shenzhen, was handed down on December 30, 2019.

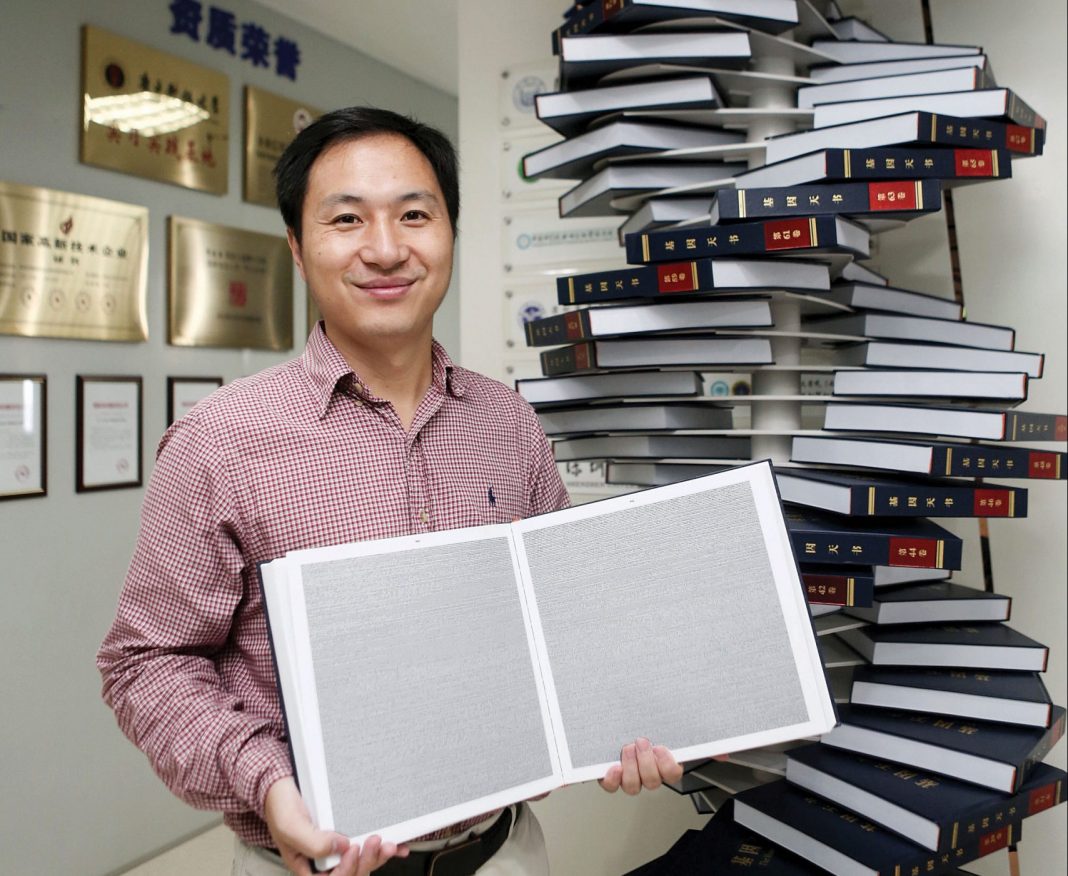

In the dock, entering a guilty plea, was He Jiankui (“JK”), PhD, the 35-year-old Chinese scientist who became a household name in November 2018 following the shocking revelation of the birth of gene-edited “CRISPR babies.”

The sentence: three years in prison, a fine of 3 million Yuan (about $430,000), and a ban from further research in “assisted reproductive technologies.” Two of JK’s former colleagues—Zhang Renli, MD, and Qin Jinzhou—were also found guilty and handed suspended sentences of 24 and 18 months, respectively. All three men pleaded guilty to the charge of “illegal medical practice.” (There is no law in China expressly against editing human embryos.)

GEN had a front-row seat at the ethics conference in Hong Kong in 2018 when JK, facing hundreds of journalists and dismayed scientists, tried to defend his work on editing human embryos. By disrupting the CCR5 gene, JK hoped to mimic a naturally occurring variant in the human population that confers HIV resistance.

But as was evident then—and has become even clearer in excerpts of the scientific manuscript he attempted to publish—he failed. (In November 2018, JK submitted a scientific report describing the editing of the CRISPR babies to Nature, but it was rejected. He resubmitted it to the Journal of the American Medical Association, which also turned it down. In December 2019, excerpts of JK’s manuscript appeared in The CRISPR Generation, a book by Kiran Musunuru, MD, PhD, and in an article by Antonio Regalado in MIT Technology Review.1,2

The hotchpotch mutations and evident mosaicism raise serious questions about the future health and cancer risks of Lulu and Nana, the gene-edited twins born in late 2018, as well as a third baby born about six months later.

By some measure, JK might consider three years to be a lenient sentence. The crime of “illegal medical practice” has three levels in China: For a serious offense in which no one was harmed, the maximum sentence is three years (plus a fine). In cases in which a patient has been harmed, the maximum sentence is 10 years (plus a fine), even longer for circumstances with a loss of life.

JK had a busy and lucrative career since returning to China in 2013, with stakes in multiple Chinese biotech companies. One school of thought is that the authorities want to bury the story. (The news was also released two days before the New Year, during the festive break.) The steep fine handed to JK might be a sign that the Chinese government wants to send a message about the danger of money poisoning science.

The last public appearance of JK was on the balcony of a university guest house in Shenzhen in December 2018 while under house arrest. A few weeks later, he was summarily fired from his faculty position at the Southern University of Science and Technology. A few months after that, he sold his stake in Direct Genomics, a clinical DNA sequencing firm he had co-founded shortly after returning to China in 2013.

The identities, whereabouts, and medical status of the CRISPR babies remains completely unknown. NIH director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, spoke for many late last year, when he said, “I wish we had more access to the two [sic] Chinese babies.”3 There are no indications that is going to happen.

JK has been widely portrayed as a “rogue” scientist, stubbornly defying the international consensus that CRISPR technology, for all its promise, is insufficiently precise or safe to apply to human embryo editing—at least for now. He also persisted despite protests and advice from several prominent American confidantes, including the Stanford University trio, William Hurlbut, MD, Matthew Porteus, MD, and JK’s postdoc supervisor, Stephen Quake, PhD.

But did JK’s “circle of trust,” which also included Nobel laureate Craig Mello, PhD, extend to senior members of the Chinese scientific establishment? One such figure is Yu Jun, PhD, one of the co-founders of the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI). Jun, dressed casually in a blue T-shirt, was an official observer during at least one of the informed consent sessions led by JK. (Yu, who is a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, did not respond to requests to comment.)

Going away

Reactions to JK’s prison sentence ran the gamut. “What JK did was criminal: he broke laws of ethics and medicine, endangered lives, and stained an entire field for no reason other than hubris,” said Fyodor Urnov, PhD, scientific director of technology and translation of the Innovative Genomics Institute at Berkeley, where he works closely with CRISPR pioneer Jennifer Doudna, PhD.

For her part, Doudna took a slightly more conciliatory tone. “As a scientist, one does not like to see scientists going to jail, but this was an unusual case,” she told the Associated Press.5 JK’s work, she added, was “clearly wrong in many ways.”

JK’s confidante, Stanford’s Hurlbut, expressed mixed emotions about a sad story: “Everyone lost in this (JK, his family, his colleagues, and his country), but the one gain is that the world is awakened to the seriousness of our advancing genetic technologies.”

“Jail isn’t the right punishment [for JK], but just because we can do something with science doesn’t mean we should,” countered Scott Gottlieb, MD, the former FDA commissioner. “Setting aside the extreme risk, there’s no compelling case to edit germline cells for use in reproduction that PGD [preimplantation genetic diagnosis] can’t accomplish.”

Perhaps the most startling response came from Josiah Zayner, PhD, the biohacker who was profiled in the Netflix documentary series Unnatural Selection. Zayner is CEO of The ODIN, a company that helps people perform genome editing at home. In an op-ed in STAT, Zayner considered JK’s historic position in the brief history of human germline editing.6

“As long as the children He Jiankui engineered haven’t been harmed by the experiment, he is just a scientist who forged some documents to convince medical doctors to implant gene-edited embryos,” he wrote. “The four-minute mile of human genetic engineering has been broken. It will happen again.

“Not much is stopping people from doing embryo editing and implantation. It won’t be long until the next human embryo is edited and implanted.”

Moratorium motion

Few would agree with Zayner. Last year, a group of leading scientists led by Broad Institute director Eric Lander, PhD, Canadian bioethicist Francoise Baylis, PhD, and genome editor Feng Zhang, PhD, issued a call for a temporary, global moratorium on heritable genome editing.7 Lander suggests that the moratorium should last five years, which is ample time for the two international commissions—under the auspices of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) and the World Health Organization (WHO)—to publish their reports over the next 12 months. These reports should offer a roadmap for how the international community should proceed.

A moratorium, Lander acknowledges, would not have prevented the actions of JK. “That wasn’t the point of it,” Lander said. Rogue actors will conduct criminal acts; people still murder each other despite laws against murder. JK’s actions were China’s responsibility.

But despite the widespread condemnation of JK’s actions, not everyone thinks a moratorium is the best response. Doudna conspicuously declined to co-author Lander’s proposal, while Harvard’s George Church, PhD, dismissed such calls as “posturing.”

Santa Clara University law professor Kerry Lynn Macintosh, PhD, argues that a global moratorium might encourage nations to ban germline editing indefinitely, or deter basic research to improve the safety and precision of the technology.8 And, she says, a moratorium might embolden nations “to adopt or maintain laws and regulations that stigmatize children born with modified genomes.”

Bartha Knoppers, PhD, law professor at McGill University in Montreal and a member of the NASEM commission, said the renewed call for a moratorium was “troubling,” writing with her colleague, lawyer Erika Kleiderman, that it might create “an illusion of control over rogue science and stifle the necessary international debate surrounding an ethically responsible translational path forward.”9

In October 2019, The CRISPR Journal (a sister publication of GEN), published a special issue devoted to the ethics of human genome editing. Anchoring the issue, Hank Greely, JD, Stanford University law professor, effectively dismantles the argument that the human genome—“the heritage of humanity” as UNESCO calls it—should be kept inviolate.10 That said, the circumstances in which germline editing offers a medical benefit that would be impossible using preimplantation genetic diagnosis are extremely rare.

The situations Greely views as the most compelling include cases in which an individual is homozygous for a dominant trait (such as Huntington’s disease), or when both members of a couple are homozygous for a recessive trait (such as cystic fibrosis or nonsyndromic hearing loss—see this article’s last section). Surprisingly, despite the outrage over the JK saga, a Russian scientist has signaled his interest in following suit.

Too soon?

With JK out of the public eye, the world’s attention in germline editing shifted last year to Moscow. An ex-wrestler named Denis Rebrikov, PhD, proclaimed his determination to perform germline editing. “I can see the billboard now: ‘You choose: a Hyundai Solaris or a Super-Child?’” Rebrikov said.

Rebrikov, a geneticist at the Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University, focused on a hereditary form of deafness, caused by mutations in the GJB2 gene. He set about recruiting Russian couples who were interested in having Rebrikov perform germline editing on embryos to correct the faulty gene with the intent of restoring hearing.

Last year, Bloomberg reported an extraordinary meeting of Russian medical experts attended by Vladimir Putin’s daughter, Maria Vorontsova, a healthcare executive.11 (Putin has spoken publicly about CRISPR and the prospect of genetically engineered super-soldiers.) But the Russian authorities have since closed ranks to thwart any immediate ideas Rebrikov may have.

Further afield, there might be instances where germline editing will be used for enhancement rather than disease correction. One could compose a list of cosmetic or behavioral traits that might prove attractive targets. For example, speaking to the Financial Times,12 Robin Lovell-Badge, PhD, a leading developmental biologist at the Crick Institute in London and a member of the WHO commission on germline editing, said: “Some people will want to never allow germline genome editing because they think it’s bad for humanity. That scares me. I don’t like closing and locking doors. Take global warming—we might need to modify ourselves.” But that is well down the road.

Who is right? Zayner, the biohacker, who asserts that thousands of edited embryos will be born during this century. Or Urnov, the veteran genome editor, who says germline editing has no medical justification and is a classic case of “a solution in search of a problem”?

The story is just getting started.

References

1. Musunuru, K. The CRISPR Generation: The Story of the World’s First Gene-Edited Babies. Bookbaby. Pennsauken, NJ.

2. Regalado, A. China’s CRISPR babies. MIT Technology Review. 3 Dec. 2019.

3. Davies, K. NIH Director Backs Moratorium for Heritable Genome Editing. GEN. 8 Nov. 2019.

4. Osborne, H. Chinese Scientist He Jiankui Jailed for Creating World’s First Gene Edited Babies ‘In The Pursuit Of Personal Fame And Gain.’ Newsweek. 30 Dec. 2020.

5. Moritsugu, K. China convicts 3 researchers involved in gene-edited babies. AP. 30 Dec. 2019.

6. Zayner, J. CRISPR babies scientist He Jiankui should not be villainized—or headed to prison. STAT. 2 Jan. 2020.

7. Lander E.S., Baylis F., Zhang F., Charpentier E., et al. Adopt a moratorium on heritable genome editing. Nature. 2019 Mar; 567(7747): 165–168.

8. Macintosh, K.L. Heritable Genome Editing and the Downsides of a Global Moratorium. The CRISPR Journal. 9 Oct. 2019.

9. Knoppers, B.M., Kleiderman, E. Heritable Genome Editing: Who Speaks for “Future” Children? The CRISPR Journal. 9 Oct. 2019.

10. Greely, H.T. Human Germline Genome Editing: An Assessment. The CRISPR Journal. 9 Oct. 2019.

11. Kravchenko, S. Future of Genetically Modified Babies May Lie in Putin’s Hands. Bloomberg. 29 Sept. 2019.

12. Ahuja, A. Crossing ethical red lines in gene editing. Financial Times. 27 Dec. 2019.