Single-use bioreactors have given industry the option of scaling out rather than up by running multiple units in parallel. Similarly, cell line development advances have produced expression systems able to generate ever higher titers. Such technologies are usually marketed based on their ability to support intensified production processes, increased output, and lower production costs.

However, while product cost may be a factor, companies that invest in technologies to intensify production processes usually take a wider range of business factors into consideration, according to Ron Rader, president of the Biotechnology Information Institute.

“In my experience, it seems that rather than just saving money or reducing COGs, biotechnology professionals and companies dream of simplifying and downsizing their manufacturing and drastically reducing infrastructure, staff costs, utilities, space and investments,” he says. “Companies do, try or aspire to do process intensification as much as they can, if not all the time at least cyclically. Products naturally go through phases of development with manufacturing scales increasing. Likewise, management always seeks and rewards cost savings.

“Most bioprocessing professionals’ jobs, particularly at larger companies, include constantly or even primarily seeking process intensification, higher efficiency, doing better or more with the same or less.”

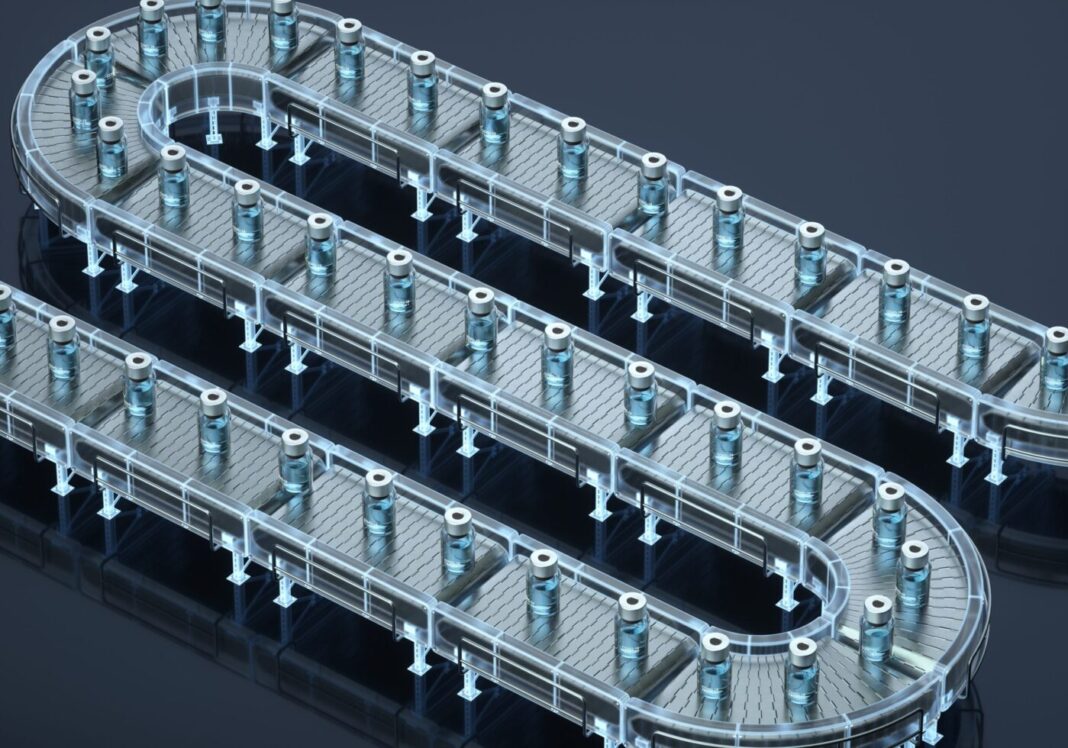

Continuous growth

Rader cites the use of continuous rather than batch-mode production as an example, explaining that companies that choose to manufacture products 24/7 are usually doing it for reasons other than production cost.

“In most cases [for companies] going with continuous bioprocesses, the end COGs are higher or much the same as for those using batch-based production, although it can depend on what is included as costs,” he explains. “But there are usually many other overwhelming benefits, notably much greater flexibility, adaptability, smaller-scale everything apart from culture media-related requirements.”

There are also competitive reasons for choosing to intensify production processes using new technologies and manufacturing methods adds, Rader.

“Process intensification is also a good defense against biosimilar competition. Repeatedly changing manufacturing processes, known as manufacturing drift, complicates things for biosimilar developers,” he says. “In addition, “if the intensified process is patentable or proprietary, the market exclusivity period of the products being manufactured may effectively be extended and there could even be opportunities for technology licensing.”

Future

Whether these factors prompt more biopharmaceutical companies to try to intensify production processes going forward remains to be seen. However, Rader says, the technology sector is still using the promise of doing more with less as a selling point.

“The vendors are now going all out promoting and hyping continuous bioprocessing, which conveniently for them requires totally new manufacturing equipment, processing technology, facilities, and regulatory approaches,” he tells GEN. “At different times, demand is technologically well ahead of what is available and at other times new technology is ahead of the demand and market. For attaining high titers, the technology is well advanced and readily available and implementable.

“For doing continuous bioprocessing, the technology is still lagging. It’s not like everybody or even many are currently adopting, for example, current single-use multi-column continuous chromatography or even more established perfusion systems for mainstream commercial manufacturing.”