March 1, 2014 (Vol. 34, No. 5)

British Gerontologist Tackles Age-Related Diseases Using Regenerative Medicine

Spend a moment asking yourself, “What is the world’s worst problem?”

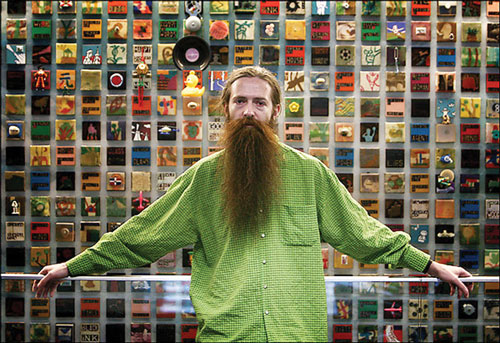

Biomedical gerontologist Aubrey de Grey, Ph.D., has an answer that may be radically different from yours. For him, it’s aging, and he not only makes a convincing case for why this is so, but he’s devoting his life to doing something about it. Dr. de Grey is the founder of SENS, a research foundation that aims to help build the regenerative medicine industry, an industry that arguably has the best chance for curing the diseases of aging. Surprisingly, he’s having more success than the people who were calling him a maverick and a heretic five years ago ever imagined.

Let’s start with why he believes that aging is the world’s worst problem. “When you consider what causes the largest amount of suffering in the world,” he begins, “it’s easy to focus on aging. Ninety percent of health care is for age-related diseases, and ill health causes more suffering than anything else.”

He goes on to talk about how worldwide there are 150,000 deaths each day, and 100,000 of them come from age-related diseases. And of course these statistics don’t take into account the pain and suffering leading up to those deaths.

Dr. de Grey’s approach to aging is different from the work of gerontologists. His goal isn’t to tweak metabolism or to make lifestyle changes that slow aging and the deteriorating health that accompanies it. Instead, his goal is to apply the principles of regenerative medicine to preventing and reversing age-related ill-health and to do this by repairing the damage of aging at the level where it occurs.

“What I’m talking about,” he says, “is looking, feeling, and functioning as you were in your early adulthood. I don’t mean ‘healthy for your age,’ I mean ‘healthy’ whether you’re in early adulthood or much older.”

In his view, “Many things go wrong with aging bodies, but at the root of them all is the burden of decades of unrepaired damage to our cellular and molecular structures. Over the decades, as each essential microscopic structure fails, tissue function becomes progressively compromised—imperceptibly at first, but ending in the slide into the diseases and disabilities of aging.”

He sees the age-related diseases as sparing young adults simply because they take a long time to develop. “One or more of the age-related diseases will affect everyone who lives long enough,” he states. “They are side effects of the body’s normal operation, as opposed to being caused by infections or other external factors.”

A key tenet of Dr. de Grey’s thinking is that there is no distinction between aging and the diseases of old age. It follows that if aging isn’t just an abstract concept, but instead a collection of diseases, then the consequence is that the diseases of aging can potentially be treated just surely as the diseases that affect younger people can be treated.

In Dr. de Grey’s view, the diseases of aging all come about due to an accumulation of cellular and molecular damage to our tissues, and this damage occurs over time. To deal with these diseases, he wants to encourage a new approach to medicine: regenerative therapies that remove, repair, replace, or render harmless these cellular and molecular changes.

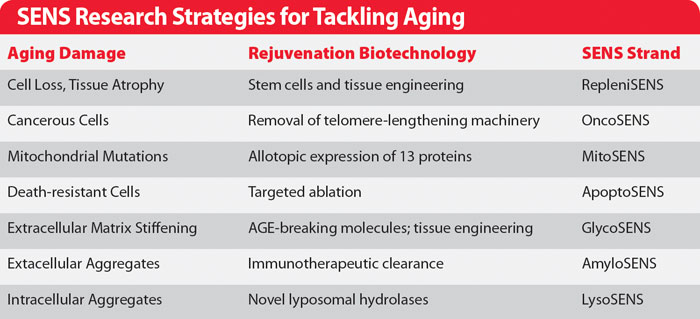

The universe of therapies needed to accomplish these goals is surprisingly small. “Decades of research in aging people and experimental animals has established that there are no more than seven major classes of such cellular and molecular damage,” he says.

“We can be confident that this list is complete,” he continues, “because scientists have not discovered any new kinds of aging damage in nearly a generation of research. I’ve been challenging people for 10 years to add to this list, and it’s standing the test of time.”

To see how treating age-related diseases could work in practice, he takes the example of Alzheimer’s disease. “A person with Alzheimer’s by definition, has senile plaque, neuron tangles, and nerve cells that die without being replaced. The SENS approach is divide and conquer by addressing each of these separately.”

Since others outside of SENS are working on two of these problems, plaque removal and repairing nerve loss, SENS researchers are focusing on getting rid of tangles. “We’re making progress. Right now we think that the work we’re doing in cardiovascular disease and macular degeneration may lead to an effective way of getting rid of tangles.”

Aubrey de Grey

Funding Aging Research

The SENS Foundation, a public charity based in California, tries to fill a niche in the research funding chain. Private sector research, particularly in the drug industry, has funds to drive research, but only after it’s clear that the odds of success are good, the time frame is reasonably short, and the potential for profit is large. Public sector funding is available for basic research that doesn’t have an immediate commercial purpose.

In Dr. de Grey’s view, there’s an area between private and public funding that is often overlooked. Research that may yield commercial success (and public benefit) may be too immature to attract private funds. “We exist to make sure that this kind of intermediate research is not neglected,” he says.

An example of this is the SENS work on cardiovascular disease. “Industry has statins that delay the progression of atherosclerosis, but part of how they work is, they lower levels of the kind of cholesterol that’s good for us, and this means undesirable side-effects. Our approach is to deal with the real problem by going after only the kinds of cholesterol that are the originators of atherosclerosis.”

SENS researchers are developing new enzymes not found in the human body. They have published some proof-of-concept research, and they expect to publish mouse model studies. When this happens, private sector funding is likely to be forthcoming. But SENS was needed for the intermediate research. Dr. de Grey wants to see all strands of regenerative medicine make progress, since it will take all of these strands to cure aging.

People no longer refer to Aubrey de Grey as a “maverick” or “heretic.” “These days, I’m more often called ‘controversial,’” he notes approvingly. “Controversial,” after all, can be translated as, “might be right.”

SENS Research Strategies for Tackling Aging

Mitzi Perdue is GEN’s corresponding editor.