Patricia F. Fitzpatrick Dimond Ph.D. Technical Editor of Clinical OMICs President of BioInsight Communications

Next-generation and mitochondrial DNA sequencing provide the keys.

As the use of mitochondrial DNA analysis has increased, so have revelations about population genetics and the evolution of human traits.

Last July, researchers reported that they had found a direct genetic link between the remains of Native Americans who lived thousands of years ago and their living descendants. Scientists used mitochondrial DNA to track three maternal lineages from ancient times to the present, comparing the complete mitochondrial genomes of four ancient and three living individuals from the north coast of British Columbia, Canada.

The findings not only will cause population experts to rethink ancient migrations into this area, but according to advocates for native populations, will solidify these groups’ claim to their ancestral homelands.

“Having a DNA link showing direct maternal ancestry dating back at least 5,000 years is huge as far as helping the Metlakatla prove that this territory was theirs over the millennia,” said Barbara Petzelt, an author and participant in the study and liaison to the Tsimshian-speaking Metlakatla community, one of the First Nations groups that participated in the study.

According to the authors, the case studies they presented demonstrate the different evolutionary paths of mitogenomes over time on the Northwest Coast, and may revise current ideas about ancient migrations.

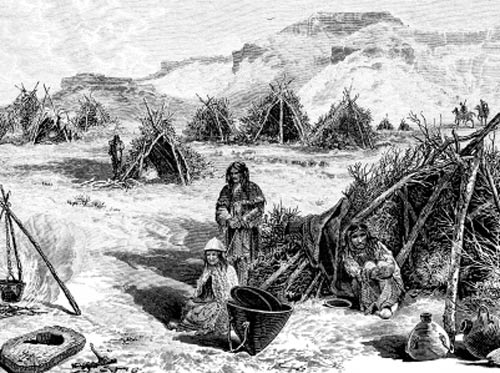

Oral traditions and some written accounts say that the north coast of British Columbia has been home to the indigenous Tsimshian, Haida, and Nisga’a people for “uncounted” generations. While some archeological sites date back several millennia, until the PLOS ONE report published last July, no hard evidence tied current inhabitants to ancient human remains in the area, some of which are 5 to 6,000 years old.

The new results provide molecular anthropological evidence consistent with nearby archaeological evidence suggesting a fairly continuous occupation of the region for the last 5,000 years.

Commenting on the study results, anthropological geneticist Jennifer Raff, Ph.D., of Northwestern University commented, “What’s particularly interesting about this paper is that the authors found two mitochondrial lineages in the Northwest Coast region in both the ancient individuals and modern people living in the area. This suggests that there’s a long continuity of occupation of this region.”

Apart from putting current native claims to ancestral homelands, these and other findings, facilitated by HGS and mitochondrial DNA sequencing technology, will cause anthropologists to rethink long-standing theories about the origins of how native people arrived in North America.

The Mitogenome

To gain a better understanding of North American population history, the investigators generated complete mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) from four ancient and three living individuals of the northern northwest coast of North America, specifically the north coast of British Columbia. The mitogenomes of all individuals were previously unknown and assigned to new sub-haplogroup designations D4h3a7, A2ag, and A2ah.

The scientists said that mitogenomic DNA studies allowed more detailed analyses of presumed ancestor–descendant relationships than sequencing only the HVSI region of the mitochondrial genome, a more traditional approach in local population studies. The results of this study provide contrasting examples of the evolution of Native American mitogenomes. Those belonging to sub-haplogroups A2ag and A2ah exhibit temporal continuity in this region for 5,000 years up until the present day.

Focusing on the mitogenome is a good way to study the evolutionary history of these groups, commented Ripan Malhi, Ph.D., a molecular anthropologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who directed the study with colleagues at several other institutions. He commented that DNA is often degraded in ancient remains, and unlike nuclear DNA, which is present in only two copies per cell, mitochondria are abundant in cells, giving researchers many DNA duplicates to sequence and compare.

He further noted that another complication associated with analyzing nuclear DNA in Native Americans involves the European influence. “There’s a pattern of European males mixing with Native American females after European contact and so lots of the Y chromosomes in the community trace back to Europe,” he said. The mitogenome offers a clearer picture of Native American lineages before European contact, he said.

To date, the only complete mitochondrial genome from an ancient Native American individual came from an archaeological site in Greenland with a radiocarbon date of approximately 4,000 years BP.

M. Thomas P. Gilbert, Ph.D., of the Center for Ancient Genetics, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, and colleagues at several other institutions sequenced a mitochondrial genome from a Paleo-Eskimo obtained from ~4,000-year-old permafrost-preserved hair, the genome representing a male individual from the first known culture to settle in Greenland. The investigators recovered 79% of the diploid genome, an amount they said is close to the practical limit of current sequencing technologies.

The investigators identified 353,151 high-confidence single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), of which 6.8% had not been reported previously, and used functional SNP assessment to assign possible phenotypic characteristics of the individual that belonged to a culture whose location has yielded only trace human remains. By comparing the high-confidence SNPs to those of contemporary populations, the investigators could find the populations most closely related to the individual. This provides evidence for a migration from Siberia into the New World some 5,500 years ago, independent of that giving rise to the modern Native Americans and Inuit.

The sample, the authors said, proved distinct from modern Native Americans and Neo-Eskimos, falling within haplogroup D2a1, a group previously observed among modern Aleuts and Siberian Sireniki Yuit. This result suggests that the earliest migrants into the New World’s northern extremes derived from populations in the Bering Sea area and were not directly related to Native Americans or the later Neo-Eskimos that replaced them.

Other scientists have used mitochondria DNA (mtDNA) variations to study physiological adaptations enabling populations to live under certain climactic and geographical conditions. Scientists working in China recently reported that mitogenomic analysis among the Sherpa population could help explain this ethnic group’s successful adaptation to the low-oxygen environment of the Tibetan highlands, and their mountaineering skills.

The investigators sequenced the complete mtDNA genomes of 76 unrelated Sherpa individuals, explaining that, generally, Sherpa mtDNA haplogroup constitution was close to Tibetan populations. However, they found three lineage expansions in Sherpa, two of which (C4a3b1 and A4e3a) were Sherpa-specific. Thus, the investigators proposed, mtDNA variations might be important in the highland adaption, given the mitogenome’s role in coding core subunits of oxidative phosphorylation.

As Dr. Mahli says, “This is the beginning of the golden era for ancient DNA research because we can do so much now that we couldn’t do a few years ago because of advances in sequencing technologies. We’re just starting to get an idea of the mitogenomic diversity in the Americas, in the living individuals as well as the ancient individuals.” And clearly, these advances can also begin to characterize the adaptation of populations to diverse climates as well.

Patricia Fitzpatrick Dimond, Ph.D. ([email protected]), is technical editor at Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News.