Whatever the particulars of the dishes consumed may be, western diet is characterized by high fat and sugar content.

A new study reported in the journal Cell Host & Microbe unravels the mechanistic underpinnings between a western diet and inflammation in the gut. The findings provide novel insights into pathways linking obesity and disease-driving gut inflammation and identifies new molecular targets to treat inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) in patients.

“We set out to investigate whether diet-induced obesity–specifically caused by a diet high in fat and sugar, or a ‘western diet’—is one of the environmental factors that can lead to impaired Paneth cell function,” says Cleveland Clinic’s Thaddeus Stappenbeck, MD, PhD, chair of Lerner Research Institute’s Department of Inflammation & Immunity.

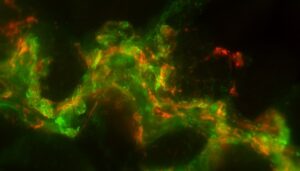

The article titled, “Western diet induces Paneth cell defects through microbiome alterations and farnesoid X receptor and type I interferon activation,” demonstrates that a western diet, similar to genetic diseases such as Crohn’s and environmental factors, damages a type of anti-inflammatory immune cell in the intestines called Paneth cells that protect us against microbial imbalances and infectious pathogens.

Whereas Crohn’s genetically disables Paneth cell function, a western diet leads to Paneth cell dysfunction through mechanisms dependent on the microbiome.The authors show in mouse models, consumption of a western diet for as little as 4 weeks leads to Paneth cell dysfunction.

The primary role of the microbiome in western diet mediated Paneth cell defects, the authors show, is to facilitate the conversion of primary to secondary bile acid. Earlier studies show, western diet in mice increases Clostridium—a genus of Gram-positive bacteria that includes several human pathogens—which can mediate the conversion of primary to secondary bile acids.

The authors in the current study show western diet in conjunction with Clostridium spp. increases the secondary bile acid deoxycholic acid levels in the ileum of the gut, which in turn inhibited Paneth cell function.

“When we started to look into large-scale datasets for the specific mechanisms that might connect the high-fat, high-sugar diet with the Paneth cell dysfunction, a secondary bile acid called deoxycholic acid caught our attention,” says Stappenbeck.

The investigators show increased levels of deoxycholic acid, a metabolic byproduct of intestinal bacteria, increases the expression of two downstream molecules, farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and type I interferon (IFN) within intestinal epithelial cells.

Stappenbeck says, “For the first time, we showed how coordinated elevation of FXR and type I IFN signals in multiple cell types contribute to Paneth cell defects in response to a diet high in fat and sugar. In previous research, stimulating FXR has shown to help treat other diseases, including fatty liver disease, so we are hopeful that with additional research we can interrogate how the combination of elevated FXR and IFN signals can be targeted to help treat diet-induced gut infections and chronic inflammation.”

In addition to their animal model studies, the researchers also evaluate data from 900 individuals to report elevated body mass index (BMI) is associated with abnormal Paneth cells among patients with Crohn’s disease and non-IBD patients.

The western diet that the researchers use in their animal model studies contains nearly 40% fat and a higher proportion of simple carbohydrates, which resembles the diet of an average U.S. adult. After eight weeks on the diet, the group that ate the western diet had more abnormal Paneth cells than the group that ate a standard diet.

Two months after the emergence of Paneth cell defects, the researchers observed increased gut permeability, where bacteria and toxins can enter the gut. This is well-linked with chronic inflammation.

Switching to a standard diet from the western diet completely reversed the Paneth cell abnormalities. While the team was interested to learn that changing the diet regimen reverses the pathological changes, more research would be needed to determine if this reversal also occurs in humans, says Stappenbeck.