This year, Sangamo expects its Pfizer-led Hemophilia A gene therapy candidate SB-525 to progress toward Phase III, while two wholly-owned gene therapies are also set to progress: phenylketonuria candidate ST-101 is now in preclinical studies with a planned IND submission in 2021, while the first patient is set to be dosed with Fabry disease candidate ST-920 in a Phase I/II trial.

Also expected to enter Phase I/II trials are two ex vivo cell therapies. One is wholly owned TX200, an autologous Chimeric Antigen Receptor Regulatory T Cell (CAR-Treg) therapy being developed for prevention of immune-mediated organ rejection in patients who have received a kidney transplant. The other is Kite, a Gilead Company-partnered KITE-037, a cancer-fighting allogeneic anti-CD19 CAR-T cell therapy.

Longer range, Sangamo plans IND submissions for two genome regulation pipeline candidates: ST-501 for Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies (2021), and ST-502 for Parkinson’s and other alpha-synuclein diseases (2022).

Sangamo CEO Sandy Macrae, MBChB, PhD, discussed Sangamo’s manufacturing plans, and approach to therapy development in an exclusive interview with GEN Edge reporter Alex Philippidis during the J.P. Morgan conference (edited for length and clarity):

PHILIPPIDIS: Why is Sangamo building out more in-house manufacturing?

MACRAE: The field of manufacturing of viruses and cells has grown exponentially. There’s a shortage of CMOs out there. The wait lists are increasing. Sangamo has worked with Brammer Bio (acquired by Thermo Fisher Scientific last year for $1.7 billion); we were one of their oldest customers. We have a great relationship and a dedicated suite there. We have dedicated time when we need it for commercial batches.

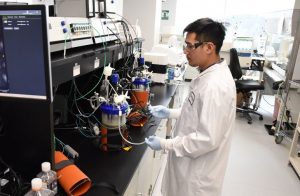

But we felt we needed to own a facility ourselves, so we built a GMP facility in Brisbane (California) that will do clinical trial material and could do small-scale commercial. That will be completed by the middle of this year. The cell therapy facility in Brisbane will be completed sometime at the end of the year, and the cell therapy facility in Valbonne in France, by 2021. It gives us control over very complicated processes. Because it’s not just the factories that are rare, it’s the people. And probably, the people are more important, and we want to recruit them, so they can make our processes as good as possible.

PHILIPPIDIS: How many new people will be at both facilities?

MACRAE: We hired 100 people last year, and we’re going to hire perhaps another 100 this year. A third of our staff are in manufacturing between Brisbane and Richmond, where our research laboratories are. We may put five in France and five in London, so the majority are here in the Bay Area.

PHILIPPIDIS: What is the cost of the manufacturing facilities?

MACRAE: We’ve never disclosed that. The one in Brisbane is now finished, so we already spent that money. Part of the reason we moved to Brisbane is the manufacturing needs large ceiling heights for all the piping and plumbing. We have a beautiful building that incorporates that, and we’ve leased a building in France to allow us to put cell therapy there.

PHILIPPIDIS: Turning to pipeline candidates, what made SB-525 attractive enough to partner out to Pfizer?

MACRAE: We look at hemophilia A and we see an area that’s large-scale, it’s commercially focused, it’s going to need reimbursement discussions, it’s competitive. And all of those things, we felt, would be better managed by a company like Pfizer. And they’ve been great partners.

They have started the lead-in study to their Phase III. They’ve given us the first [$25 million milestone payment] of $300 million in milestones. That takes us up to the commercial patient launch. And then after that, we get between low-teens and 20% royalties, which will mean that once this is on the market, it will be an incredibly important product for Sangamo.

PHILIPPIDIS: To what extent is SB-525 a model for partnering out some of Sangamo’s pipeline candidates?

MACRAE: Things that are small enough that we can do ourselves, and where we have some expertise that requires more bespoke development, we will keep ourselves. And indications such as hemophilia, oncology, probably CNS, are the kinds of things that would be better with great expertise and a partner. And we will continue to partner some things and keep some things ourselves.

For us, the most important thing is getting medicines to patients as quickly as possible. Sometimes you do it yourself, and sometimes you do it with other people.

PHILIPPIDIS: Sangamo’s pipeline candidates fall into any of four modalities: Gene therapy, ex vivo gene-edited cell therapy, in vivo genome editing, and in vivo genome regulation. Of the four, is there a preference where the company will, over time, pursue more candidates in more modality over another?

MACRAE: We talk of it like waves. To date, we do gene therapy and cell therapy. But in the near term, we will do cell therapy and genome editing. And in the future, we’ll do genome editing.

I don’t think we’ll do gene therapy much beyond two or three years from now. And then, I hope that eventually gene and genome editing will become our standard fare. Cell therapy is great because you can take the cells out, and make sure you get the delivery. But what patients are looking for is a single simple injection of something that goes to every cell we want to target and makes the changes in the DNA that they need. When you have that, all the rest are obsolete.

PHILIPPIDIS: Why is Sangamo viewing gene therapy as more near term? Is it the challenge of pricing? Of payers? Of production?

If one calculates it takes $200 to $300 million to do a drug development program at one of these, the cost of goods is the same across them all. The amount you’d be able to charge is probably very similar, somewhere between $0.5 and $3 million—which means the only thing that determines whether it’s worth doing one of these from a business point of view is the prevalence. There are very few prevalent rare diseases—medium rare diseases—that can be addressed in the liver, Hemophilia is one. Fabry is one. But if you get much smaller than Fabry, and particularly if there’s more than one company trying to do it, the numbers just can’t make sense.

Fabry makes sense, but if it was ten companies doing Fabry, it wouldn’t make sense. So we’re all looking for this unknown rare disease that is sufficiently prevalent that we could address. And it doesn’t exist. But Sangamo’s got the advantage that we’re not stuck doing gene therapy for rare diseases. Our main thrust of our technology is editing. And many gene therapy companies have come to us to try and access the editing, because they too see that they’re limited in what they can do.

PHILIPPIDIS: Given that Sangamo has numerous modalities, has the company thought to position itself more as a platform company as opposed to a drug developer?

MACRAE: It’s a great question. It’s probably the most common thing that we discuss as a board. Analysts value companies by products, so they can look at hemophilia and they know what that’s worth.

I think the value of Sangamo is the science and the platform. And we will apply it to products that we keep ourselves, because we also learn what we can do with the technology by developing it. But we will partner with many people, and put our technology in the hands of others, because eventually other people will come up with good editing. And we have a window where we must make the most of our talents.

What I want you to take away from this is, Sangamo is a company that has Phase III assets, as well as real science coming through between CNS, autoimmunity, and rare disease. But also, spending the necessary time to invest in the future, and to continue to develop the technology. And the zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) technology is remarkable. It’s one of the commonest transcripts in the body. It’s natural and human, and it’s very, very adaptable. The individual units are modular, so one is always able to come up with a solution for any part of the genome.

PHILIPPIDIS: Last year, Sangamo disappointed investors with interim results from Phase I/II trials of its ZFN genome-editing candidates SB-913 for mucopolysaccharidosis type II (MPS II), and SB-318 for MPS type I. You’ve said you will launch a new trial using second-generation ZFNs for SB-913 and define next steps for SB-318. What is the latest with the new MPSII trial?

MACRAE: That’s our in vivo genome editing product candidates. What we learned, largely from our hemophilia A program was, we weren’t delivering enough of the zinc fingers to individual cells. It works beautifully in the test tube, it works beautifully in animals. We just weren’t getting enough into the human liver.

The team has come up with some wonderful improvements that they can make, from the most prosaic of increasing the dose, putting in a version of the gene that works either way round, to improving the effectiveness of the zinc fingers, making the virus work better, and finally, finding a way to put both zinc fingers in one virus, which just increases the maths of how effective it all is.

We’ve said we’ll go back into the clinic the end of this year — but not unless and until we have something that’s significantly better. These patients have very few options, and we want to make sure that we fulfill our contract with them.

What we do is difficult, cutting-edge science, cutting-edge medicine. Every time we go in, we learn a little more. Most of the time, we think we could do something better next time. But that’s what makes us all get up and come to work.