As the legalization of marijuana continues to spread among various states within the U.S., researchers, and physicians are trying to fully grasp the potential health hazards of the recreational use of the drug. Since marijuana can be consumed through a variety of methods—e.g., eating, smoking, or vaporizing—it is important to understand if and how drug delivery methods affect users. With that in mind, a recent study from investigators at Portland State University found benzene and other potentially cancer-causing chemicals in the vapor produced by butane hash oil, a cannabis extract.

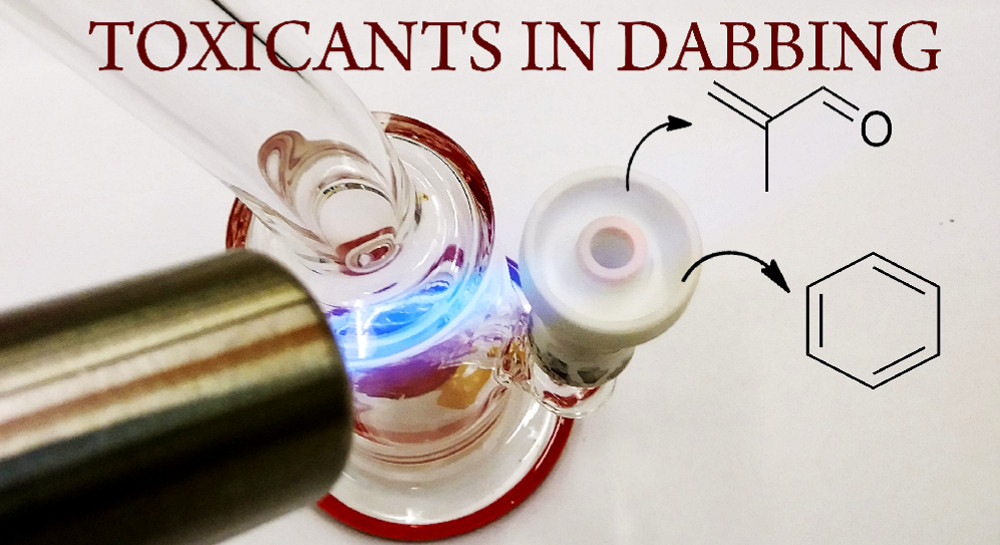

Findings from the new study—published recently in ACS Omega in an article entitled “Toxicant Formation in Dabbing: The Terpene Story”—raises health concerns about dabbing, or vaporizing hash oil—a practice that is growing in popularity, especially in states that have legalized medical or recreational marijuana. Dabbing is already controversial. The practice consists of placing a small amount of cannabis extract (a dab) on a heated surface and inhaling the resulting vapor. The practice has raised concerns because it produces extremely elevated levels of cannabinoids—the active ingredients in marijuana.

“Given the widespread legalization of marijuana in the U.S., it is imperative to study the full toxicology of its consumption to guide future policy,” noted senior study author Robert Strongin, Ph.D., professor of organic chemistry at Portland State University. “The results of these studies clearly indicate that dabbing, while considered a form of vaporization, may, in fact, deliver significant amounts of toxins.”

Dr. Strongin and his colleagues analyzed the chemical profile of terpenes—the fragrant oils in marijuana and other plants—by vaporizing them in much the same way as a user would vaporize hash oil.

“The practice of 'dabbing' with butane hash oil has emerged with great popularity in states that have legalized cannabis,” the authors wrote. “Despite their growing popularity, the degradation product profiles of these new products have not been extensively investigated.”

The authors continued, stating that the current study focused on the “chemistry of myrcene and other common terpenes found in cannabis extracts. Methacrolein, benzene, and several other products of concern to human health were formed under the conditions that simulated real-world dabbing. The terpene degradation products observed are consistent with those reported in the atmospheric chemistry literature.”

Many of the terpenes that the researchers discovered in the vaporized hash oil are also used in e-cigarette liquids. Moreover, previous experiments by Dr. Strongin and his colleagues found similar toxic chemicals in e-cigarette vapor when the devices were used at high-temperature settings. The dabbing experiments in the current study produced benzene—a known carcinogen—at levels many times higher than the ambient air, the researchers noted. It also produced high levels of methacrolein, a chemical similar to acrolein, another carcinogen.

“The results of these studies clearly indicate that dabbing, although considered a form of vaporization, may, in fact, deliver significant amounts of toxic degradation products,” the authors concluded. “The difficulty users find in controlling the nail temperature put[s] users at risk of exposing themselves to not only methacrolein but also benzene. Additionally, the heavy focus on terpenes as additives seen as of late in the cannabis industry is of great concern due to the oxidative liability of these compounds when heated. This research also has significant implications for flavored e-cigarette products due to the extensive use of terpenes as flavorings.”